A photo gallery of Lt. Col. George Custer.

-

George Custer graduated last in his class from West Point in June 1861, two months after the start of the Civil War. Despite his low marks, Custer joined the Union's 2nd Cavalry under Major General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. After demonstrating his fearlessness in crossing a river to scout enemy lines in May 1862, Custer was offered the position of Captain on McClellan’s staff.

Credit: West Point Museum -

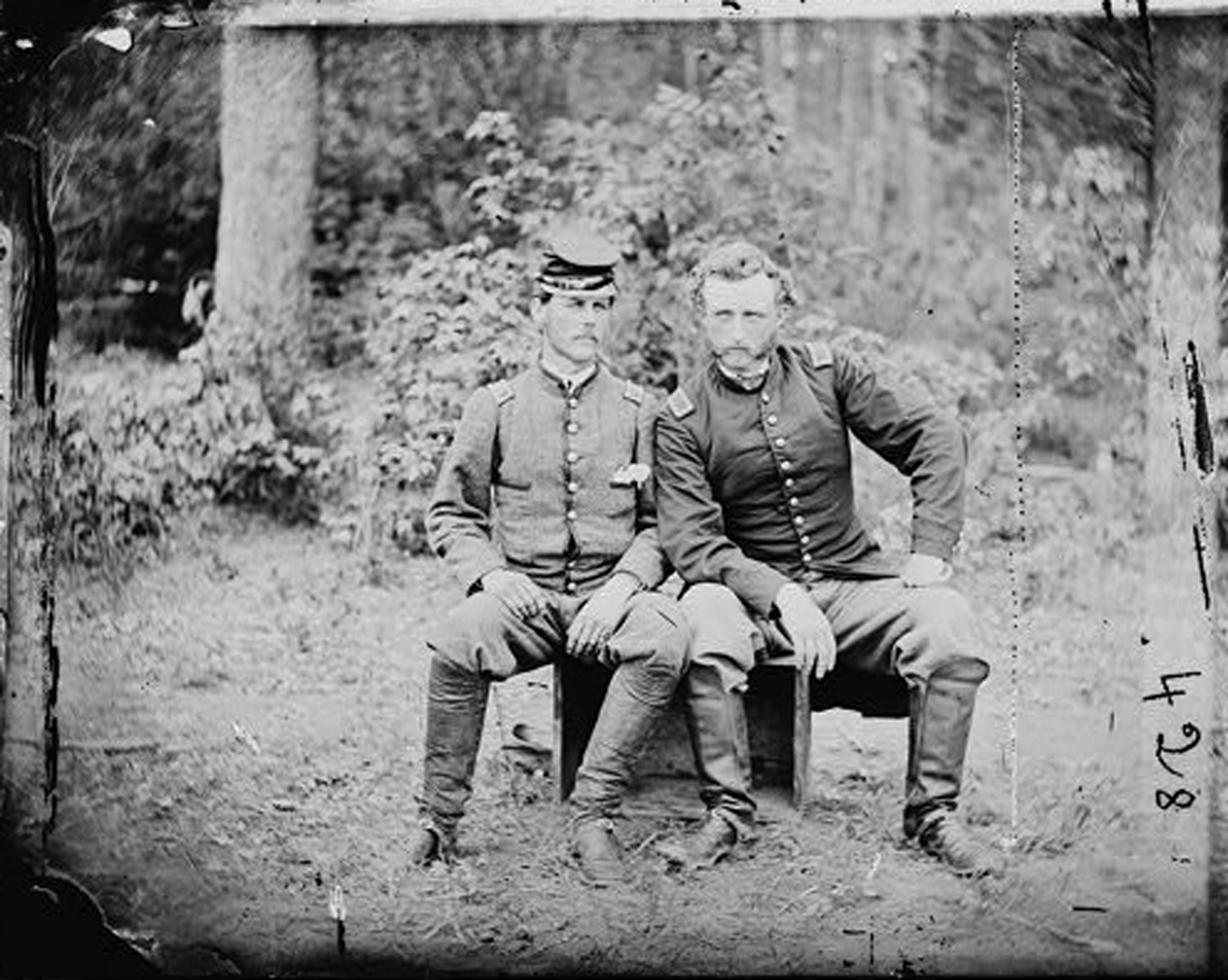

Custer and his former classmate James B. Washington, a Confederate prisoner, during the Peninsular Campaign. Though the Union ultimately saw a humiliating defeat by the Confederate Army, Custer's fearlessness was noticed by his superiors. May 31, 1862.

Credit: Library of Congress -

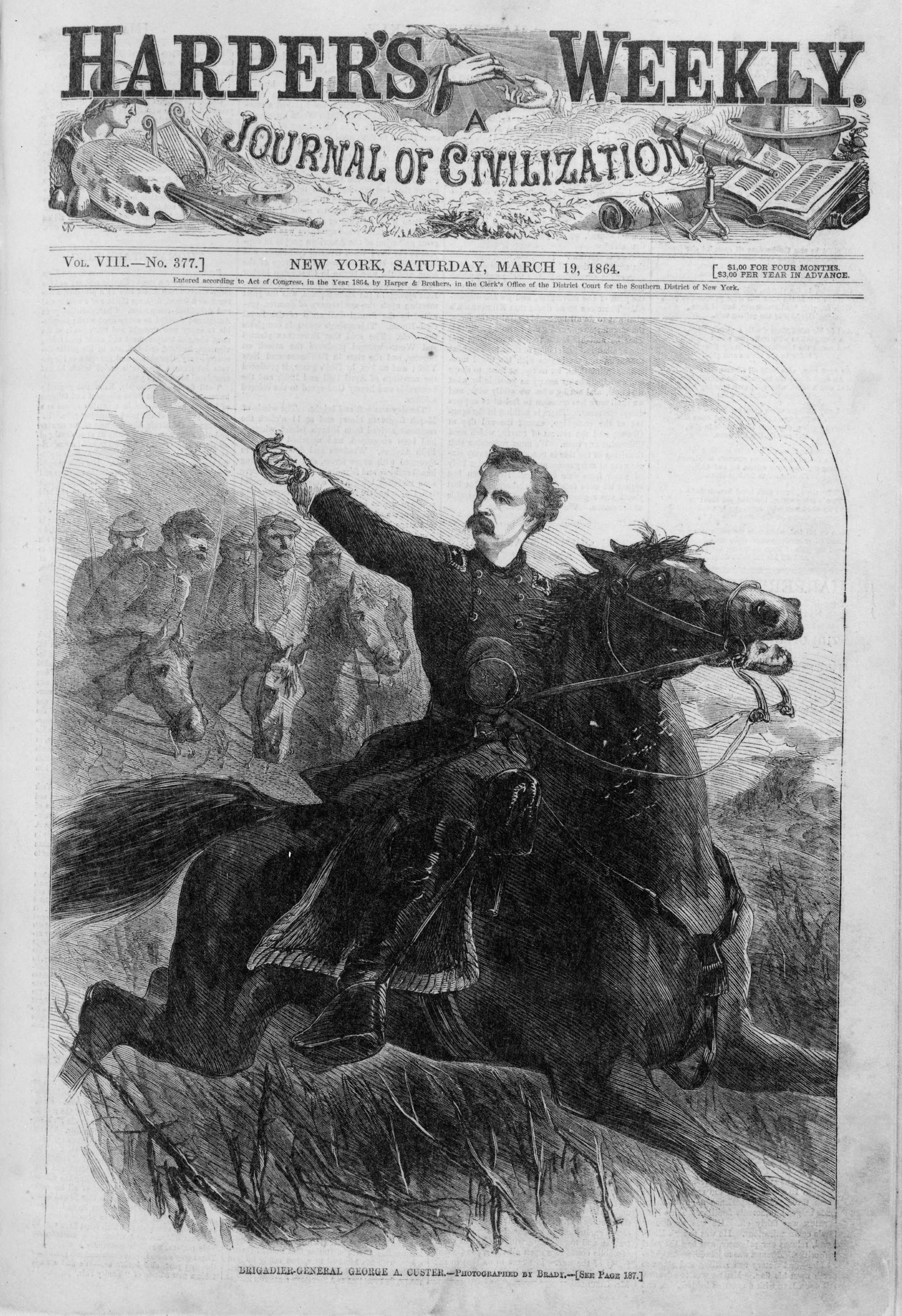

At the Battle of Gettysburg in 1864, Custer established his reputation as an aggressive cavalryman, willing to take risks and recklessly lead his men into precarious situations.

Credit: Harper's Ferry -

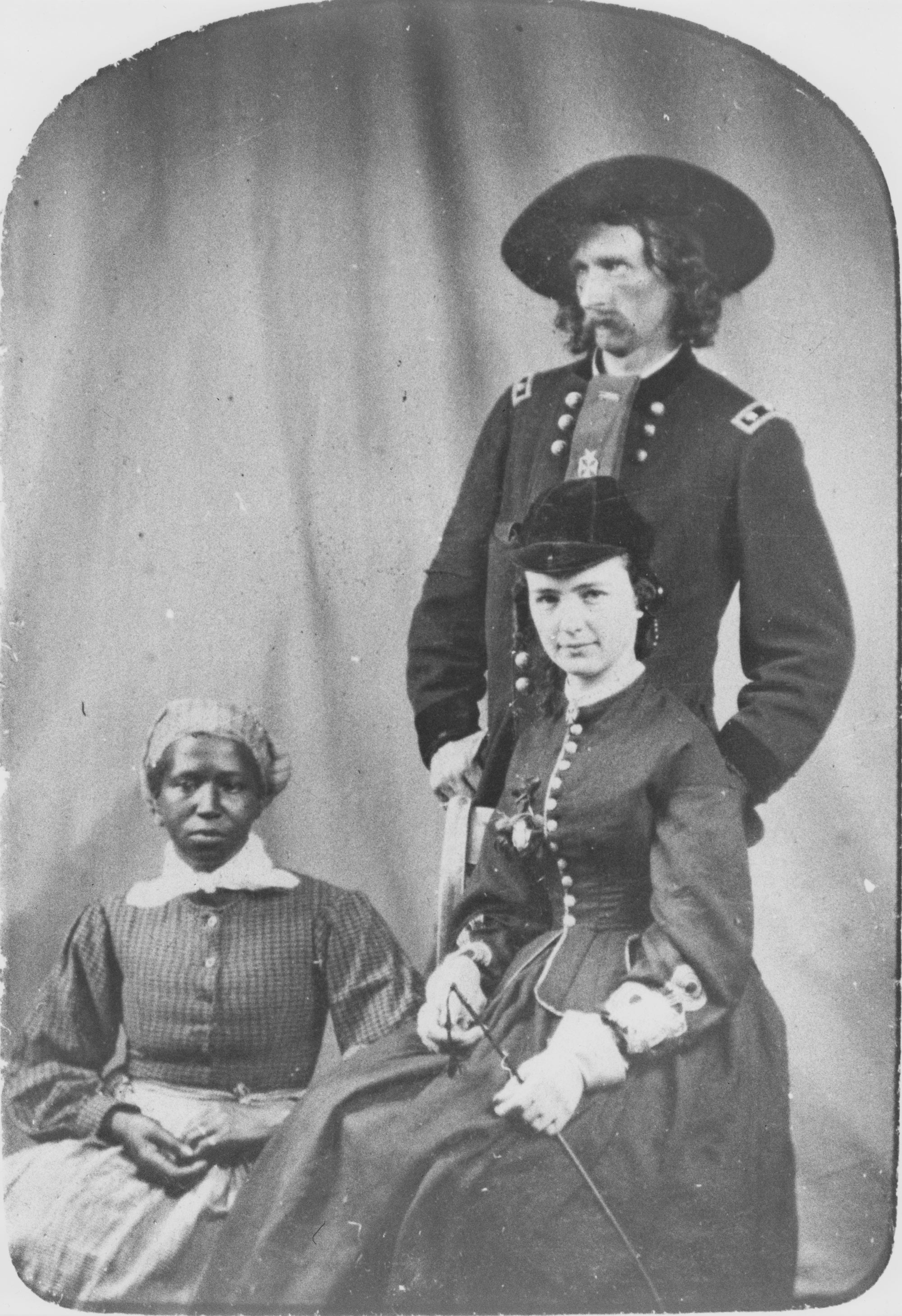

Libbie and George Custer married on February 9th, 1864. The devoted couple spent much of the following decade together, with Libbie often following George to the battlefront. After a lengthy separation in 1867 Custer impulsively abandoned his post to visit Libbie, ultimately earning a court-martial and a yearlong suspension.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

Eager to return from his suspension, Custer accepted General Sheridan’s order to march from Fort Dodge to the Washita River to attack Black Kettle, the Southern Cheyenne peacemaker who led efforts to resist American settlement. Here, in November 1868, Custer stands at Sibley Tent near Fort Dodge with Osage scouts.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

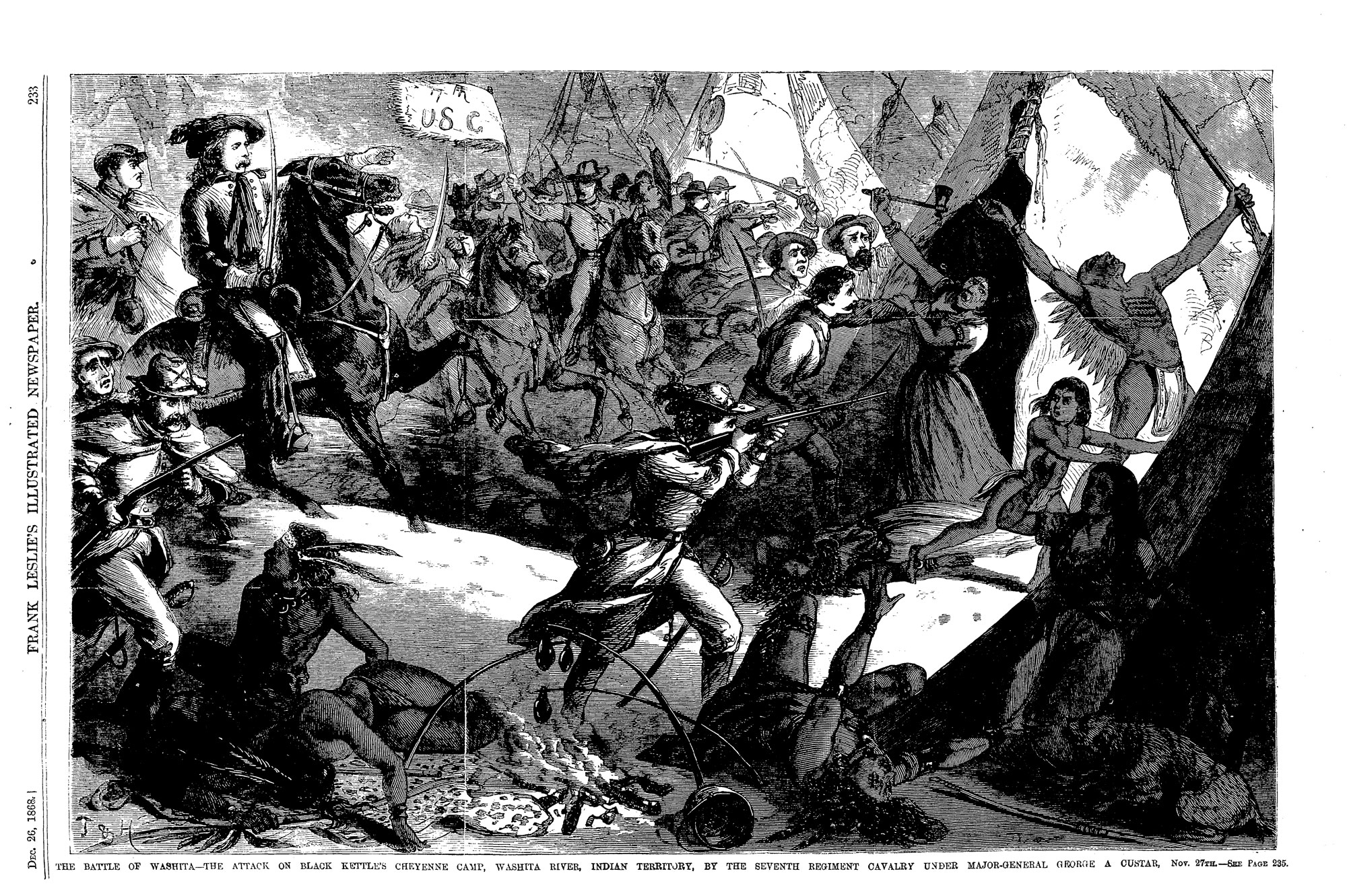

Custer’s ruthless winter attack of Black Kettle’s Cheyenne reservation saw roughly 100 Indian casualties, and the death of Black Kettle himself. The massacre at Washita earned Custer a reputation as the greatest Indian fighter in the plains, and the hero of the American frontier.

Credit: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper -

During the summer of 1869, Custer and the 7th cavalry were stationed at Big Creek camp in Kansas. The newly expanded Kansas Pacific Railroad ferried hundreds of tourists to the area. Americans were eager to sample life in the Wild West and to catch a glimpse of the notorious General Custer and his charming wife, Libbie, who was stationed with her husband for the summer.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

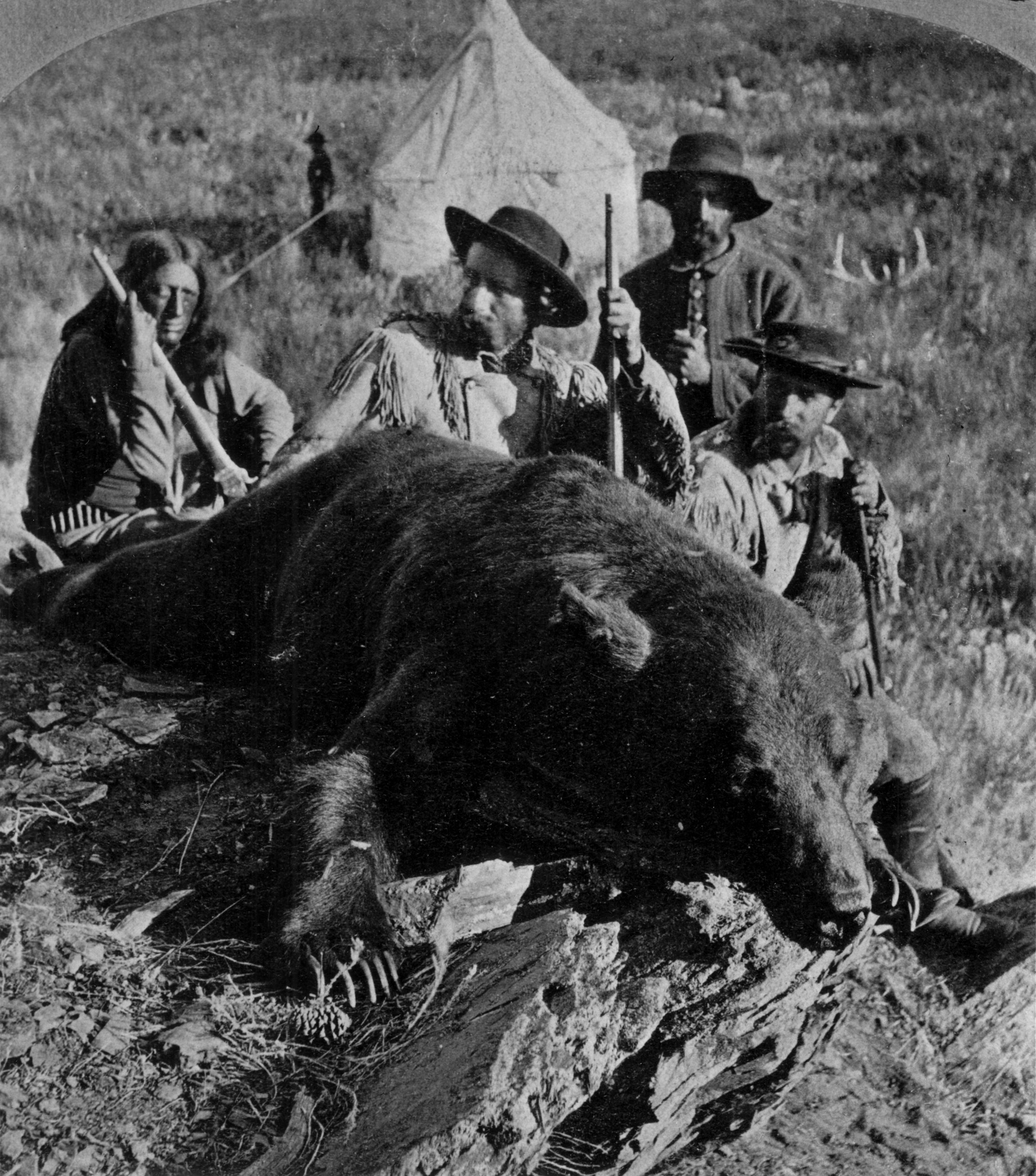

Hunting photos taken at Big Creek highlighting exotic frontier animals such as buffalo helped promulgate the romantic image of the western plains. By promoting the allure of the West, Custer hoped to gain support for further exploration and expansion.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

Posing in hunting garb in 1872, Custer nurtured his image as a hunter and plainsman while at Big Creek camp, further developing his reputation as an explorer of the Western frontier.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

Custer with an elk during the Yellowstone Expedition in 1873. Custer and the 7th Cavalry escorted and protected men from the Northern Pacific Railroad survey as they explored territory around Dakota, Wyoming and Montana.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

In November 1873, Custer and Libbie moved into Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory. This fort not only served to help ensure the expansion of the Northern Pacific Railway, but it was also a base from which the 7th Cavalry could establish American military power on the Northern Plains.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

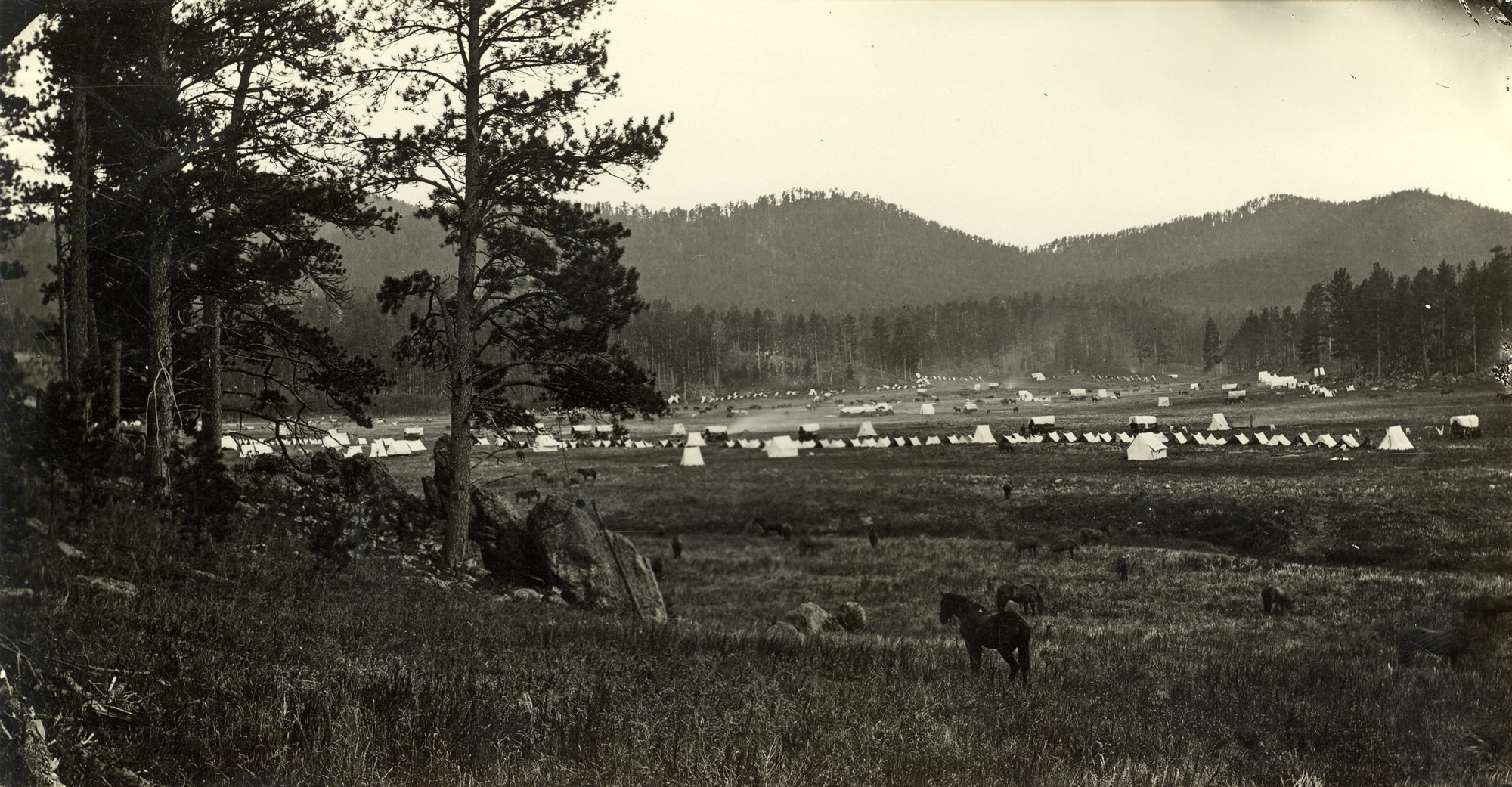

In July 1874, Custer led The Black Hills Expedition scouting locations for a new fort and charting a route to the southwest. Unofficially, men also searched for gold, the presence of which had been rumored from expeditions several years earlier.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

Custer sought to demonstrate the glory and unexplored wealth of the Black Hills to the American public through widely circulated photographs such as this. The fact that the Hills were still under Lakota control did little to stop exploration, specifically in search of gold, exacerbating tensions with the native population.

Credit: National Archives -

Between expeditions on the plains, Custer and Libbie entertained at their home in Fort Lincoln, which served as the headquarters for social activity. July 1875.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

The 7th Cavalry saw more action in 1875, when an influx of white Americans to the Black Hills in search for gold antagonized the Native Americans, who saw the region as sacred. Tensions increased between the Indians and the U.S. government.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

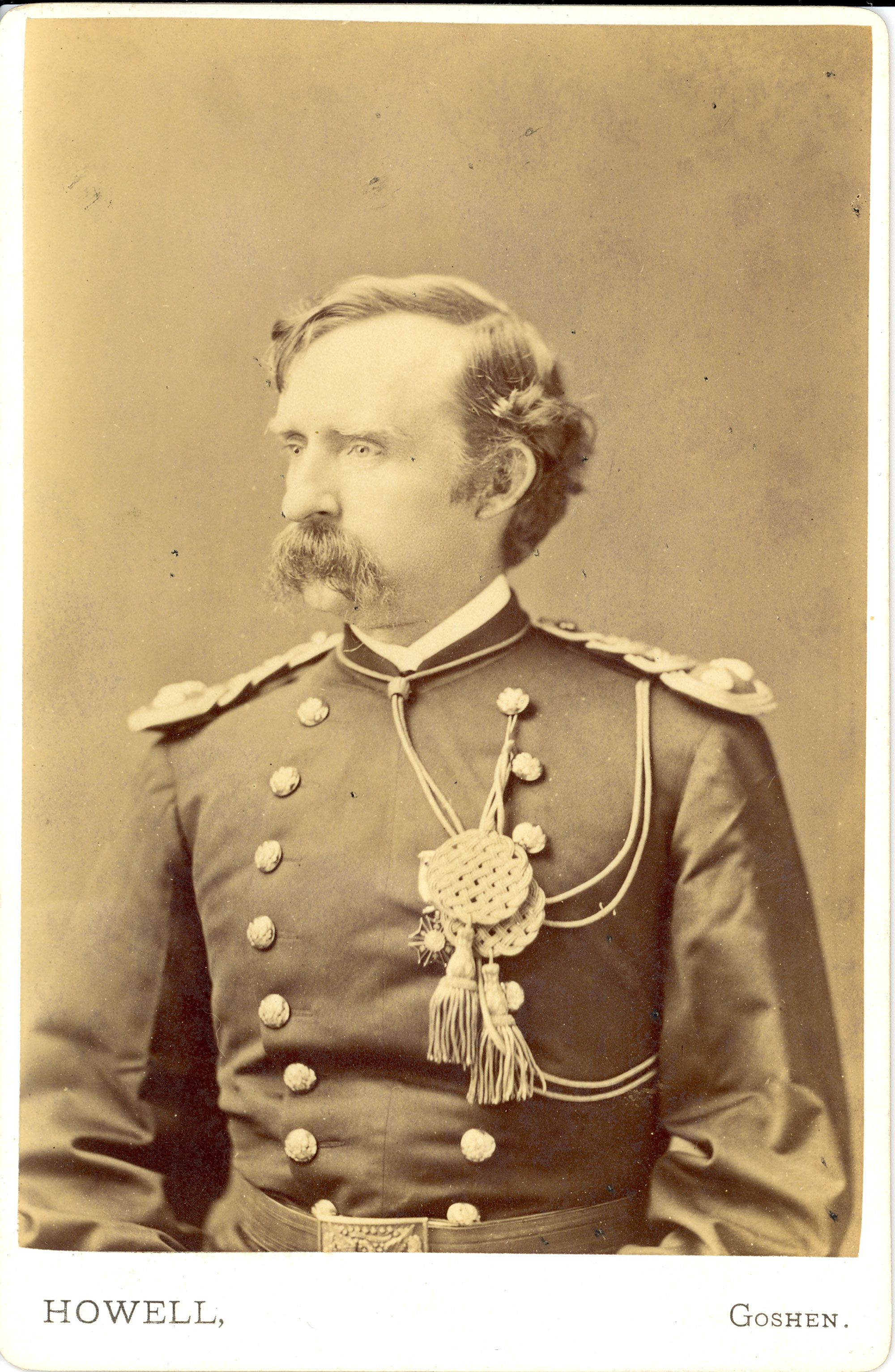

Three weeks after Custer sat for this portrait in New York City on April 23, 1876, the 7th Cavalry joined the Sioux War — a large military effort to round up the remaining free Indians in the Black Hills. Most U.S. troops assumed an easy victory.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument -

On June 25, 1876, at the Battle of Little Bighorn, Custer and his troops faced overwhelming Indian opposition. No U.S. cavalrymen survived, and the event came to be known as Custer’s Last Stand.

Credit: Library of Congress -

After Custer's death, Libbie protected the General's legacy, promoting his image as a ruthless, Indian-fighting, heroic American military icon, who sacrificed his life in pursuit of the frontier.

Credit: Little Bighorn Batlefield National Monument