Getting Away with Murder

No one served time for the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. But history holds these three accountable.

Roy and Carolyn Bryant and J. W. Milam will always be linked to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. In the minds of many, they live in history as the trio that got away with murder.

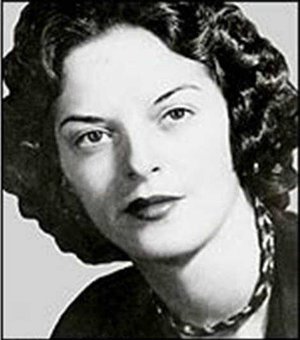

Carolyn Bryant, the daughter of a plantation manager and a nurse, hailed from Indianola, Mississippi, the nucleus of the segregationist and supremacist white Citizens' Councils. A high school dropout, she won two beauty contests and married Roy Bryant, an ex-soldier.

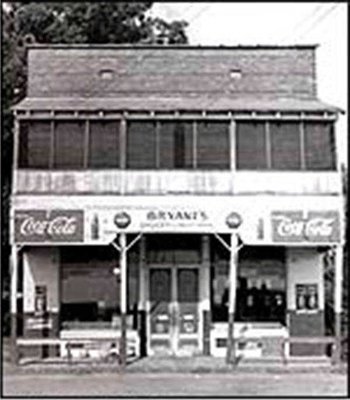

The couple ran a small grocery, Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market, that sold provisions to black sharecroppers and their children. The store was located at one end of the main street in the tiny town of Money, the heart of the cotton-growing Mississippi Delta. They had two sons and lived in two small rooms in the back of the store.

To earn extra cash, Roy worked as a trucker with his half-brother J. W. Milam, an imposing man of six-feet-two inches, weighing 235 pounds. Milam prided himself on knowing how to "handle" blacks. He had served in World War II and received combat medals.

On the evening of August 24, 1955, Emmett Till went with his cousins and some friends to Bryant's Grocery for refreshments after picking cotton in the hot sun. The boys went into the store one or two at a time to buy soda pop or bubble gum. Emmett walked in and bought two cents' worth of bubble gum. Though exactly what happened next is unconfirmed. She stormed out of the store. The kids outside said she was going to get a pistol. Frightened, Emmett and his group left.

Carolyn told her sister-in-law, Juanita, who was in the back of the store with their children, what had happened. They agreed not to tell their husbands, who were out of town on a trucking job. When Roy and J. W. returned, one of the kids at the scene told them what had occurred. In the Deep South—where the separation between blacks and whites was defined by law, Roy and his half-brother decided Emmett needed to be taught a lesson.

At about 2:30a.m. on August 28, under the cover of darkness, the two white men showed up at Moses Wright's home, where Emmett was staying, and took him away. Wright said he saw a person in the car, possibly Carolyn, who helped identify Emmett. The boy's corpse would be found several days later, disfigured and decomposing in the Tallahatchie River. Moses Wright could identify the body only by an initialed ring, which had belonged to Emmett's father, Louis Till.

Bryant and Milam had already been rounded up as murder suspects, and Southern papers were decrying the "savage crime." Yet Northern outrage prompted many Southerners to resent outside agitators and rally in support of the suspects. When Bryant and Milam could not afford a legal defense, five local lawyers stepped up to represent the two suspects pro bono.

When the trial opened in September, the national and international press descended on the scene.

Roy, Carolyn and J. W. became celebrities. Some reporters talked about Roy and Carolyn's "handsome looks" and J. W.'s tall stature and big cigars. They even alluded to Carolyn as "Roy Bryant's most attractive wife" and a "crossroads Marilyn Monroe."

During the trial, the families arrived with their sons dressed in their Sunday best, Roy and J.W. in starched white shirts while their wives donned cotton dresses. Many whites in the surrounding counties showed up to watch the show. They brought their children, picnic baskets and ice cream cones. Meanwhile, African American spectators were relegated to the back and looked on in fear.

Carolyn testified under oath, but outside the presence of the jury, that Emmett said "ugly remarks" to her before whistling.

When they were acquitted, the men later sold their story for $4,000 to reporter William Bradford Huie. Two of their defense attorneys helped facilitate the interview that was published in Look magazine in January 1956. After the town's show of support at the trial, the men talked freely about how they killed the young teen from Chicago. But soon after the article came out, both men were ostracized.

Blacks stopped frequenting groceries owned by both the Bryant and Milam families. The stores soon went out of business. Unable to find work, Roy took his family to East Texas and attended welding school. His half-brother J. W. followed him soon after. Years later, both men would return to Mississippi.

In 1981, Milam died of cancer of the bone. Roy Bryant died of cancer 13 years later. No one ever did time for Emmett Till's murder.