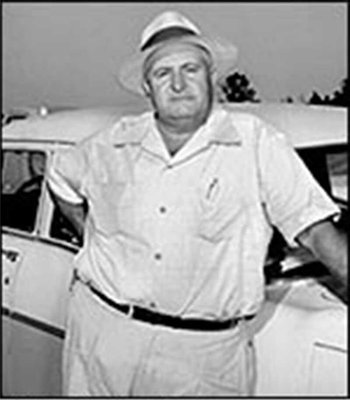

Sheriff Clarence Strider

Mississippi sheriff Clarence Strider became an unforgettable symbol of southern intransigence in the 1955 Emmett Till case.

An imposing man weighing 270 pounds, Strider was the sheriff of Tallahatchie County and a wealthy plantation owner in the heart of the cotton-growing Delta. His property could be identified from miles away by the letters S-T-R-I-D-E-R, which he insisted be painted on the roofs of sharecroppers' shacks.

Strider was the first official to learn that a body had been discovered by a young man fishing in the Tallahatchie River. He hoped to bury the body right away, and even ordered Emmett Till's Mississippi relatives to get his body in the ground by nightfall. But when Emmett's mother learned in Chicago that he had been found, she demanded that the body be sent home.

Strider trumpeted to the local press that the case would be investigated, but changed his mind once the case gained nationwide attention and scorn. In a press conference that stunned many outsiders, Strider summed up what many in the local white community felt:

"We never have any trouble until some of our Southern niggers go up North and the NAACP talks to 'em and they come back home. If they would keep their nose and mouths out of our business we would be able to do more when enforcing the laws of Tallahatchie County and Mississippi."

Strider lorded over the courtroom and refused to admit African American journalists to see the proceedings against the accused, Roy Bryant and his half-brother, J. W. Milam. When Judge Curtis Swango overruled him, Strider segregated them from the white journalists and placed them at a card table off to the side of the courtroom. Then, when African American Congressman Charles Diggs arrived from Detroit, Strider refused to let him in. A black journalist tried to explain Diggs' status to Strider, but the sheriff and his deputies remained incredulous. "This nigger said there's a nigger outside who says he's a congressman." To which another deputy replied: "A nigger congressman?"

With the trial underway, Strider made the unusual move of testifying for the defense. He shed doubt on the identification of Emmett's body, saying the corpse had been submerged too long to tell whether it was that of a white or a black person. Strider also claimed that the body pulled from the Tallahatchie was that of an adult rather than a 14-year-old boy. His testimony bolstered the main defense argument: Emmett Till was still alive and well, living in Detroit with his grandfather.

After the verdict was announced, Strider publicly congratulated the defendants.

Strider's son would later say his father was misunderstood, that he was just "doing his job" and that the press "made a red-neck hick out of him, a tobacco-chewin' fella."

"He got 'em arrested, carried 'em to jail, went before the grand jury, they got an indictment and tried 'em in a court in front of his peers and they turned 'em loose," Strider's son said. "So I don't see how they keep wantin' to bad name the sheriff and his job because he couldn't convict them. He wasn't on the jury."