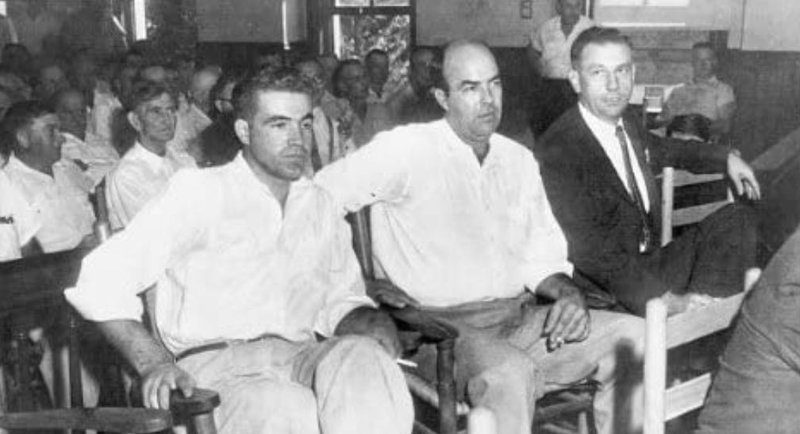

Sex and Race in 1955 Mississippi

Historians discuss the social mores that pervaded the Emmett Till case.

Q&A with historians Jane Dailey, James Horton, John David Smith, and Stephen Whitfield

Q. How did whites like Milam and Bryant see themselves in relation to blacks?

John David Smith:

It's not too much to say that the racial and social mores of slavery remained very much alive in Mississippi in 1955. While whites begrudgingly recognized that blacks were free, they were unwilling to accept them as social and racial equals. White sexuality, before and after slavery, always provided a means of white control over blacks. Till crossed the line of white propriety; he committed what whites considered a betrayal of racial lines. Till insulted Bryant's wife and insulted the very bases of white racial control and hegemony.

Stephen Whitfield:

The deference expected of blacks varied in intensity, depending on the region, and also depending on whether the setting was urban or rural, upper South or Deep South. In the Mississippi Delta in 1955, deference was about as thorough as could be imagined. Blacks were not expected to have serious opinions of their own, to exercise independence of judgment, to have the capacity to educate themselves in any advanced, formal manner, to be qualified to vote or to serve on juries (or of course to hold public office). In that part of the Deep South, whites arrogated to themselves the right to control whatever they wished of black life, and exercised the power to do so. As the forces of modernization gathered momentum, whites in the Deep South became especially keen to detect any challenges to that deference.

Poor whites like Bryant and Milam prided themselves on easy-going, informally "good" relations with blacks. So long as the etiquette of Jim Crow was understood by both sides, so long as no disruptive signals were emitted, blacks and whites seemingly got along without any overt signs of intimidation, though the threat of violence was always there, whether or not a Mississippi black was "uppity" or not. J. W. Milam made a living by renting Negro-driven mechanical cotton pickers for plantations in the Delta. He prided himself on knowing how to get along with blacks, on knowing how to "handle" them.

James Horton:

Few white residents of Tallahatchie County would have been prepared to deal with a black boy like Bobo. Bryant and Milam claimed that they had never intended to kill Till but simply wanted to beat him and frighten him by threatening him with death. But Bobo would not react as expected. He was defiant, refusing to beg for mercy or to be remorseful. Even in the face of beatings, he continued to defy Southern racial/sexual taboos, bragging to his attackers about his intimacy with white girls, and showing them the picture from his wallet to support his case. These were not the actions of black people with whom Bryant and Milam were familiar.

Q. Why was what Till did so wrong in the eyes of Milam and Bryant? Why did a whistle result in a lynching?

James Horton

Save for its horrible conclusion, Till's experience was not unique. His was the first generation in which substantial numbers of America's blacks were born and reared outside of the South. This was a generation of children who returned to their parents' birthplace to visit relatives in an environment different from that in which they were socialized. Their unfamiliarity with Southern racial etiquette often confused white Southerners and put Northern black visitors and their Southern relatives at risk and sometimes in danger... Bobo's fatal mistake was in crossing the racial/sexual line in his encounter with Carolyn Bryant.

Jane Dailey:

Most historians today see the Till lynching as linked to the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. A large and vocal segment of white southerners interpreted the Brown decision in explicitly sexual terms. For example, Walter C. Givhan, an Alabama state senator, asked about the decision, "What is the real purpose of this? To open the bedroom doors of our white women to Negro men." Beginning in 1954, white southerners used a variety of tactics to prevent this outcome. Southern congressmen declared their unwillingness to abide by the law; their action encouraged mobs to prevent the integration of schools and universities across the region. White Citizens' Councils -- known across the South as the "uptown Klan" -- put a respectable face on social and economic intimidation of Civil Rights supports, and inundated southern mailboxes with alarmist fliers promising white parents black grandchildren should they not stand together now against school integration. In this climate of cultivated white hysteria about black sexuality, eight-year old African American boys could be made wards of the state for playing a "kissing game" with little white girls (as happened in North Carolina) and the flirtatious crack of a 14-year-old boy could become a death sentence, as it did for Emmett Till in 1955.

If the whole system of segregation had not seemed besieged (as it did to white Mississippians in 1955), then Milam and Bryant probably would not have responded so violently to Till. But in this context of white fear and anxiety about African American sexuality, and about black sexual access to white women and girls, Till's actions assumed a new, more powerful, meaning.

John David Smith:

It was more than a whistle. Till allegedly touched Carolyn Bryant, propositioned her, and thus crossed over into the white man's sexual world. Till's behavior became "uncivilized" and, to the likes of extreme white supremacists, justified the actions of Bryant and Milam. People in control have historically employed extralegal or vigilante justice to enforce social customs. In this case they used racial violence to enforce community/racial standards, codes of behavior, in a ritual of racial fear and hate.

Stephen Whitfield:

Till not only engaged in a wolf-whistle, but was accused of squeezing the arm of Mrs. Carolyn Bryant and asking her for "a date." To him it was a joke, done to impress local young blacks. To her husband and his brother-in-law, it was a crude and crass violation of the etiquette of Jim Crow, an insult that required punishment, lest other blacks try to cross the color line in such a fashion. The whistle itself did not "result in a lynching." But if Bryan and Milam can be believed, in testimony they presented to a journalist, William Bradford Huie, after they had been acquitted (and could no longer be tried for the same offense), it was Till's impudence, his apparent defiance and perhaps lack of fear, that pushed the two abductors into killers.

Whether it was a lynching or not depends on the definition. If lynching means a public ritual meant to assert an ethos by killing those who overstep boundaries, a communal act of murder (often accompanied by torture), then Till's death was not a lynching. The two men (and possibly others) acted in secret. They did not intend to get caught or be prosecuted. This racially-motivated killing lacked the unashamed, public features of lynchings earlier in the 20th century.

Q. Mamie Till Mobley describes looking at her son's body and feeling relief that the killers hadn't mutilated his genitals. Why was she afraid they might?

Jane Dailey:

Mamie Mobley was afraid that her son's killers had mutilated his genitals because it was very common for lynchers to do exactly that. At the height of the Southern lynching craze (which peaked in 1892), naked black men were castrated by white men in full view of white women and children. In Atlanta in April 1899, for instance, Sam Hose was burned before a crowd of thousands for killing his employer and allegedly raping the white man's wife. Before setting him alight, his executioners cut off his fingers, ears, and genitals, and skinned his face.

John David Smith:

In their racist rage white mobs often mutilated the bodies of their male victims. This kind of gross ritualization of hate and control falls again into the realm of dehumanizing one's victims and thereby gaining a sense of moral vindication. In other words, those who enforce community standards believe that they are "civilized," while those beyond community standards (those who we interpret as "victims") could be brutalized because they were not "civilized." The fixation of white mobs on the sexual organs of black alleged rapists no doubt signified to some degree their own sexual fantasies and resulted in part from their ritualized need to project sexual control on the victims of their racist rage.

Q. Some Southerners felt lynchings protected the virtue of white women. Why was that important to them?

Jane Dailey:

It has often been important to various groups of men to protect what they call the virtue of the women they consider theirs. In "protecting" a woman's sexual purity, a husband (or father or brother) protects his monopoly on her sexual favors. Protecting the virtue of southern white women meant more than that for white southern men, though. White women personified the South itself -- its mind, its essence, its timeless continuity. White supremacists equated any attack on white womanhood with an attack on the South, and vice versa. As the Pulitzer-prize winning southern author W. J. Cash put it in 1941, any assault on the segregated South would be felt as an assault on white women, and "the South would inevitably translate its whole battle into terms of her defense." In punishing Emmett Till, Bryant and Milam thought they were protecting the white southern way of life. "Protecting" white womanhood was the lynchpin of an ideology, and not just a rhetorical stance.

John David Smith:

Of course whites always positioned their women on a pedestal as they abused black women sexually and psychologically. There are several levels of possible analysis here. By establishing an unrealistic place for white women, white men provided the necessary psychic distance to exploit all blacks and create the mythology of the purity of "mothers" who gave birth to southern white culture. The "untouchable" white women stood in contrast to those black women who, because of their alleged "uncivilized" place in the hierarchy of peoples, had no control over their bodies and who bore the brunt of white racial and sexual exploitation of people of color in the Old and New Souths.

Stephen Whitfield:

The Southern whites who believed that "lynchings protected the virtue of white women" were making several assumptions. One is that white women needed protection, that left on their own they might be intimate with black men, or would be unable to protect themselves against the advances of black men. Another is that lynchings were the consequence of rape or attempted rape, which constituted only a minority of the accusations for which this horrendous and barbaric punishment was the result. Finally there was the assumption that white women were virtuous (which was untrue in the notorious case, involving two white tramps or prostitutes), and that all black men furtively desired white women and would under the right circumstances assault them. White Southern men tended to believe even at mid-century that the aim of the Civil Rights movement was racial intermarriage, whereas the right to marry the spouse of one's choice irrespective of race was in fact the lowest item on the priorities of those seeking racial equality in the United States.

Q. Did lynching replace slavery as a means for whites to control blacks?

John David Smith:

Lynching existed along the frontier in all societies and whites employed the device to control "outsiders" throughout the course of southern history. After emancipation, however, lynching and other forms of racial violence provided whites the means to control, to regulate, and to keep African Americans in check. With the legal bonds of slavery removed, whites found in racial violence both a practical means to control blacks but also the means of keeping blacks fearful and perpetually marginalized in southern society. The threat of white violence, in addition to economic and social controls, maintained the controls of slavery in the post-emancipation age.

Q. Why was intimate contact between the races so taboo?

Jane Dailey:

Intimate contact between the races was taboo for a variety of reasons. One important reason had to do with the way Jim Crow discrimination worked in the realm of the law. The point of segregation was to keep black southerners in their separate and inferior places. To do that, the state had to be able to tell who was who. In order to do that, like had to marry like. For more than 300 years, state legislatures wrote laws that defined whiteness for the purpose of marriage. Depending on the state and the decade, people who were more than half black, or a fourth black, or an eighth black, or 1/16 black, or even 1/32 black, could not marry anyone defined at law as white. These laws were the lodestar of segregation, because without controls on sex, racial classification became impossibly complicated. Interracial sex -- what white southerners called miscegenation -- undercut all forms of segregation based on genealogy.

John David Smith:

Intimate contact suggested degrees of shared humanity that slavery, then semi-slavery (peonage, convict lease, sharecropping, farm tenantry) sought to suppress. It also suggested the loss of white control over whom, whites or blacks, would control the racial and social control dynamics of a racially-hierarchical society. Whites could have intimate contact with blacks on the whites' terms but not vice versa. Whites feared that once black men were their sexual equals (ie. having white female sexual partners), that the whites' entire social structure would collapse. Some scholars see sexual control at the core of racial control mechanisms throughout southern history.

Q. Some white slaveowners raped their slaves, though. What about that?

John David Smith:

As I've said above, whites defined blacks in such ways that some whites could justify raping black women. Recent scholars point to the domestic slave trade as the best example of the open, blatant, and perpetual sexual exploitation of blacks, especially women but of men as well. While white women allegedly were shocked by the sexual activities of their husbands and sons, miscegenation was so pervasive that I think it was justified and accepted by whites of all classes as part of the whites' "Herrenvolk democracy." Whites viewed blacks as uncivilized people with no rights that whites were bound to respect.

Q. Didn't whites and blacks ever fall in love?

Jane Dailey:

Whites and blacks often fell in love. There are many instances of interracial love affairs and marriages, from the colonial period through emancipation and Jim Crow and on into the present. Perhaps the most famous couple in the modern era are Richard and Mildred Loving, who married in 1958, were arrested for violating Virginia's anti-miscegenation law, and who challenged that law successfully before the Supreme Court. The decision that made restrictions on interracial sex and marriage is thus called, appropriately, Loving v. Virginia!

John David Smith:

Obviously yes. As brutalizing as slavery was, human emotions certainly were involved in interracial sexual partnerships. Too much of the scholarship on this derives from autobiographical and literary accounts. But "love across color lines," as the German scholar Maria Diedrich notes in her recent book, no doubt existed between slaves and masters and complicates a simple narrative of master-slave relationships.

Q. How are things different today?

John David Smith:

As in history, today people of all ethnic backgrounds are attracted to others of different ethnic backgrounds. Today white southerners seem to be more tolerant of interracial partnerships, but I would argue that this is neither universal nor across-the-board. The farther one lives from a metropolitan community the more one observes stares at interracial couples and the more likely interracial couples are to encounter the social opprobrium of their communities. Ideas die hard and many whites still are uncomfortable with the reality of "racially-mixed couples."

Stephen Whitfield:

The Till case looks more ambiguous than it did in 1955, because of the emergence of feminism. In 1955 no decent human being, no citizen endowed with a conscience, could fail to be revolted by the price that Emmett Till paid for his braggadocio. That is still true. But the feminist movement that had begun to emerge a decade later also saw something sinister in what Till in his joking adolescent way did, which was to assume that females could be "taken" by any males bold enough to make advances upon them. A wolf-whistle was no longer a matter of amusement, but came to be seen as an example of an unpleasant aggressiveness that women no longer needed to endure or make light of.

I should add that the trial, even though it resulted in the injustice of an acquittal, brought to light the horrendous excess to which white supremacists would go to perpetuate "the Southern way of life." The shock of the murder and of the subsequent exoneration produced an outrage that would burst into the Civil Rights movement that crested within the decade, and quite a few activists who helped doom Jim Crow have testified to the emotional impact that the Till case exerted upon them.