Sharecropping in Mississippi

The Mississippi Delta — where "cotton was king."

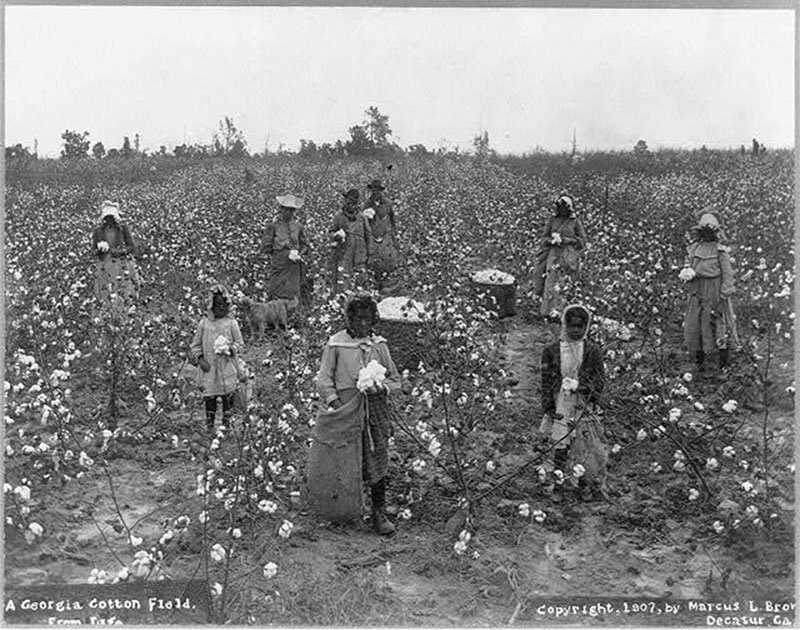

The Delta plantation system started in the 19th century when white farmers went there in search of fertile farmland, escaping declining productivity in other Southern states. They brought with them slaves to do the backbreaking work of clearing the wild forest and subduing the Mississippi River with levees. As a result of the slaves' labor, the Delta became the richest cotton-farming land in the country. Long and flat, and with breathtaking views, the Delta stretches 200 miles from Memphis, Tennessee, down to Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The Delta may have been beautiful, but work there was hard. Slavery and cotton production became synonymous with the Southern economy and Mississippi. Since the Mississippi Delta was the last area of the South to be settled, after the Civil War, the state became among the most reactionary and repressive states for African Americans. Blacks lived with the daily and ever-present threat and reality of violence.

Although blacks outnumbered whites, the sharecropping system that replaced slavery helped ensure they remained poor and virtually locked out of any opportunity for land ownership or basic human rights. The system grew from the struggle between planters and ex-slaves on how to organize production. Planters wanted gang labor, like they had used under slavery, to work the fields; freed people wanted to own and work their own land.

Under the system, the sharecropper rented a plot of land and paid for it with a percentage of the crop -- usually 30 to 50%. Sharecroppers would get tools, animals, fertilizer, seeds and food from the landlord's store and would have to pay him back at incredibly high interest rates. The landlord would determine the crop, supervise production, control the weighing and marketing of cotton, and control the recordkeeping.

"We'd get $12 per bale and we had to pick hard in order to have money to buy food during that season," said Mississippi State Senator David Jordan, whose parents were sharecroppers. "If we had a rainy week where we couldn't pick at all, then we would have no money. We would have to go get food and substances on credit."

At the end of the year, sharecroppers settled accounts by paying what they owed from any earnings made in the field. Since the plantation owners kept track of the calculations, rarely would sharecroppers see a profit.

"Some came out in the hole five or six times and they never did get out of the hole," Jordan said. "So what happened, they caught the midnight train or bus and headed to Chicago and they never found 'em, 'cause that was the only way to get out of that miserable situation."

Between 1910 and 1970, 6.5 million blacks went North,leaving the South, the cotton fields, and sharecropping behind. By the end of World War II, much of cotton farming had been mechanized, and sharecroppers were thrown off the land. Some 5 million blacks left after 1940, creating the second great migration to the North. In Chicago, which had a direct train route from Mississippi, the black-owned newspaper The Chicago Defender urged blacks to migrate, and lobbied railroads to offer group rates for travelers. Black porters working on the trains distributed The Defender onboard.

With African Americans leaving the South en masse and the unstable price of cotton during wartime, Mississippi planters and white businessmen worried about their economic stability. Threatened by the Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, some whites took action, forming Citizens Councils to ensure that blacks would be blocked from economic success. Mississippi was among the last Southern states to integrate the schools and allow blacks to vote.

Mechanization and migration put an end to the sharecropping system by the 1960s, though some forms of tenant farming still exist in the 21st century.