Separated from her own mother as a child, Doris spent much of her youth in foster homes. When she applied for Social Security in 1979, she didn’t have a birth certificate. So the agency attempted to verify her age through the institution where Doris had once been interned: the Lynchburg Training School and Hospital, formerly the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded.

By then, Dr. K. Ray Nelson was the director of the training school. The letter he received from Social Security was the tip he’d been waiting for. Doris Figgins was Carrie Buck’s sister.

Nelson had been looking for Carrie Buck since he started at the training school in 1973. “No one knew what happened to her after she’d been sterilized and discharged from this institution,” he told a reporter.

“I thought ... there should be more to the story than that. Here was an individual involved in probably the most dramatic and important bit of legislation affecting the mentally retarded in this country before or since.”

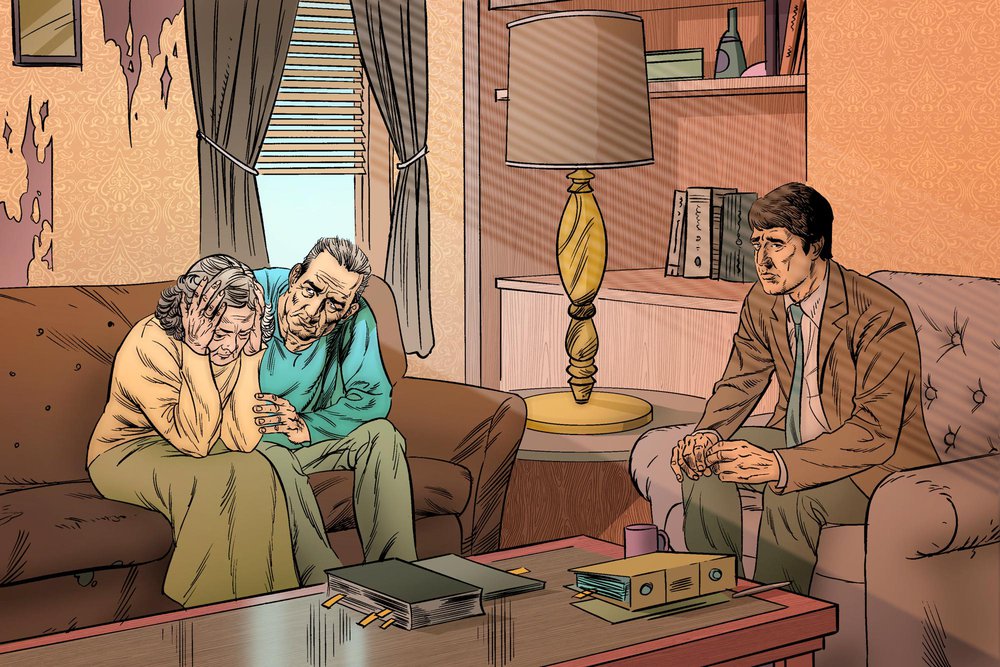

In the summer of 1979, Dr. Nelson goes to see Doris and Matthew, who have now been married some 40 years. Sitting in their living room, he tells Doris her date of birth and the date she was sterilized. Doris starts to cry. She had not known. All these years, she thought her childlessness was her fault.

Doris was sent to the Virginia Colony at age 12, accused of promiscuity and feeble-mindedness.

Now she remembers an operation she had there. She always thought it was an appendectomy.

She had no idea that after her sister Carrie was sterilized under Virginia’s new law, the colony board voted to step up eugenic sterilizations. Now she learns that she was selected in the first group of women sterilized under the expanded program. She was 16.

Doris doesn’t know why she was sterilized. Perhaps they were experimenting on her. “Guinea pigs,” she says. “Just taking us and butchering us up like hogs.”

“She had a right to know,” Nelson says.

Now the public will know, too. The story about Doris and Matthew Figgins appears in Charlottesville’s local paper, The Daily Progress, under the headline “‘I Wanted Babies Bad’: Woman Told of Her Sterilization.” Soon, national outlets pick up the story. People begin to wonder what happened to Doris’s sister. A trickle of reporters go looking for Carrie Buck.

PART III

Weeks after being sterilized, Carrie was released on parole from the Virginia Colony. At trial, colony representatives had testified that after her surgery, Carrie would be able to move back into the Dobbs home, where she could spend time with her daughter, Vivian. Instead, she was placed in the home of a different family. The arrangement seemed satisfactory, until her employers claimed she used a dishpan as a chamber pot and sent her back to the colony.

This time, Dr. Bell did try to send Carrie back to the Dobbses — but Mrs. Dobbs, who was raising Vivian on her own, refused. In Mrs. Dobbs’ view Carrie never should have been released from the colony in the first place.

Carrie was sent, instead, to live with Mr. and Mrs. A. T. Newberry, 200 miles away in Bland, Virginia. The Newberrys were pleased with her work ethic. Knowing she could be sent back to the colony at any time, Carrie stays in touch with Dr. Bell and Nurse Berry to keep them apprised of her progress.

On August 8, 1928, Carrie writes a letter to Nurse Berry. She is “real well and getting along just fine.” She is mostly concerned about her sister and mother.

She writes:

Mrs. Berry I have wrote to Doris several times since I have been here and haven’t gotten any answer from it… I had a letter from mother here several days ago and said for me to send her some things. Will it be o.k. for me to do so or not. Will you please let me know. Give her my love and tell her I will write to her later as I haven’t got time to write now as I have got some work to do.

In December, Carrie writes to Dr. Bell again, this time in an attempt to ward off a return to the colony.

Dr. Bell I am expecting Mrs. Newberry to write you about some trouble I have had but I hope you will not put it against me and have me come back there as I am trying now to make a good record and get my discharge... I guess the trouble I had will throw me back in getting it but I hope not. Give Mrs. Berry my love and best regards. I have a real nice house and you don’t know how much I appreciate it and they are just as good to me as can be.

Mrs. Newberry does indeed write to Dr. Bell. She complains that Carrie is “beginning her adultery again.” But Carrie stays on with the family even after being formally discharged from the colony on January 1, 1929. Three years later, she marries widower William D. Eagle, nearly 40 years her senior. Carrie writes to the colony that they have been together for three years and that “he is a good man.” The Eagles will stay together for the next twenty-five years. They work odd jobs, attend a Methodist church and grow their own vegetables.

Carrie could cut ties with the doctor and nurse who sterilized her, but she continues to correspond with Dr. Bell. She is worried about her mother, who is still at the colony. In 1933, she writes:

Dr. Bell I would just love to take mother out for this winter and if nothing happens so I can’t and if you will let her come I will make preparations for her to come and will meet her I do not have but two rooms but still she is welcome to come and stay with me. We live out in the country. We have a pig and a nice garden and are putting up a lot of things this summer... I will see that my mother is well taken care of and plenty to eat if you will let her come. I am real anxious for her to come.

But Emma never does. When Dr. Bell resigns later that year, Carrie loses her main contact at the colony and her letters become fewer and farther between.

But they don’t stop. In 1940, Carrie writes to the colony again to ask after her mother, whom she hasn’t heard from in a while. The new doctor there writes back that Emma is well and “happy most of the time.”

In 1944, Carrie hears that her mother is ill and travels to the colony. When she arrives with her brother Roy, the staff inform them that Emma died two weeks earlier. Emma is already buried in an unmarked grave in the colony cemetery. “The son and daughter were a bit upset,” a note in Emma’s record says. “However they were most considerate and accepted the explanation.”

By the time of her mother’s death, Carrie is a widow. In 1965, she marries again, this time to an orchard worker named Charlie Detamore. They move to a house in Charlottesville. She sees her sister Doris from time to time.

In 1980, after Dr. K Ray Nelson makes contact with the Buck women, he invites them back to what is now the Lynchburg Training School and Hospital to visit. They leave flowers on their mother’s grave. Doris returns to the operating room where her sterilization took place, but Carrie’s legs are too weak to make it up the stairs. Doris dies just two years later.

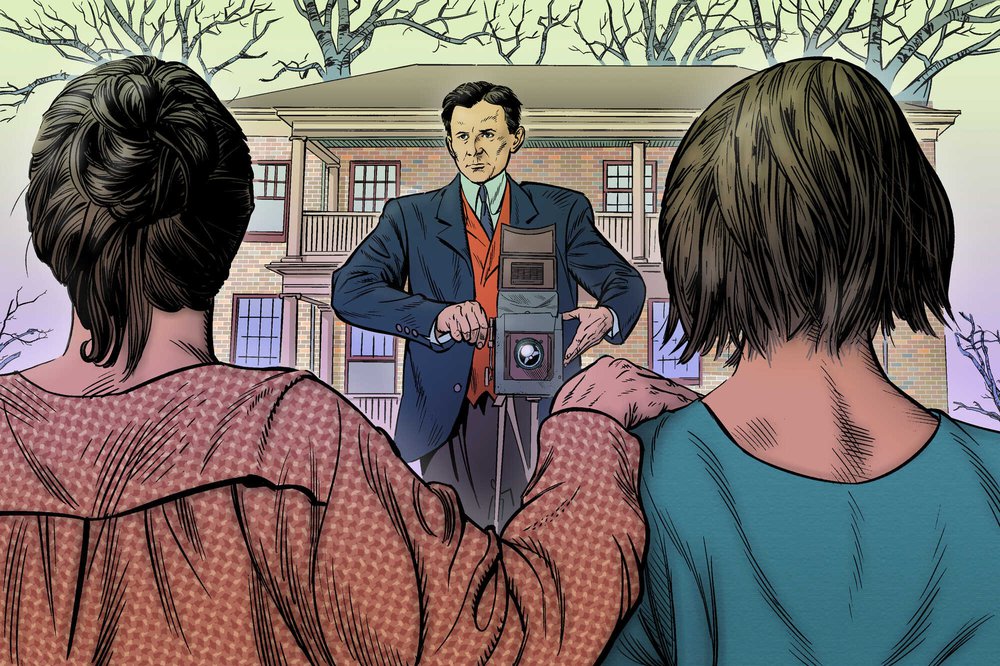

Carrie is in her 70s and not in good health when reporters and interested scholars start showing up. One of her visitors is Paul Lombardo, a law student at the University of Virginia. Lombardo arrives at the state-operated residence where Carrie is living just after Christmas in 1982. She and Charlie had been brought there after being discovered suffering from malnutrition and exposure in their Charlottesville home. Now, Lombardo finds Carrie reading newspapers and assisting a friend with crossword puzzles. Other residents consider her pleasant and intelligent. Staff note her devotion to her husband Charlie, whom she cares for the best she can. Carrie’s conversation with Lombardo is brief, but she confirms that the pregnancy that sent her to the Virginia Colony was the result of a rape. She tells others that she never wanted a big family, but she had wanted “a couple children.” She was angry, she says. “They done me wrong. They done us all wrong.”

A few weeks after visiting Carrie, Lombardo sees her obituary in the local paper. He attends her funeral on a cold day in January. By happenstance, Carrie is buried in the same cemetery as her only daughter, Vivian, who was taken away from her as a baby. Vivian died at eight years old from a stomach infection.

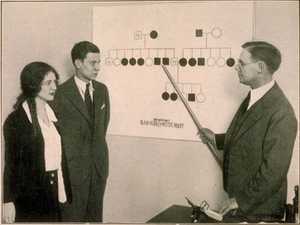

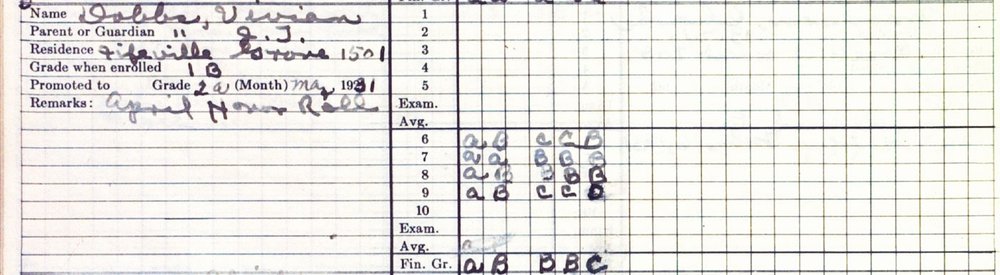

Lombardo will become a leading expert on the case of Carrie Buck. He tracks down Carrie’s grade school report cards, which show that she was a perfectly average student before the Dobbses took her out of school. He also uncovers satisfactory report cards belonging to Carrie’s daughter, Vivian, who even made the honor roll. Years later, he discovers the photographs of Carrie and Emma, and the one of Vivian, tucked away in the files of Arthur Estabrook. Finally, he restores Carrie’s surviving letters, which have been preserved on barely legible microfilm.

The letters paint a new portrait of Carrie in her own neat cursive script — one in which she is not a feeble-minded threat to society, but a thoughtful, hardworking woman, with a fierce devotion to the people she loved.

* * *

In 2002, Paul Lombardo sponsored a historical marker memorializing the story of Carrie Buck and the Supreme Court decision that changed her life.

Sources for this article include Paul Lombardo’s book Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court and Buck v. Bell, and Adam Cohen’s book Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck.

Learn more about eugenics. Watch the American Experience film The Eugenics Crusade.