Latinos and the Consequences of Eugenics

From the Collection: The U.S. Latino ExperienceBy Natalie Lira

In February 1930, Concepcion Ruiz, a 16-year-old Mexican-American, was arrested and tried in California Juvenile Court on charges of sexual delinquency. Legal officers brought the young woman before Superior Court Judge Robert H. Scott because she ran away with a boyfriend and was allegedly “subnormal.” In the eyes of California Probation Officers, Judges, and Medical Superintendents, Concepcion’s interest in boys, her decision to run away and her lower than average IQ score were enough evidence to declare her “mentally deficient.” With this diagnosis, Judge Scott committed her to the Sonoma State Home for the Feebleminded to be sterilized. On June 15 of the same year, after several months of confinement at Sonoma, Ruiz was taken to the surgery ward where she was sterilized despite vocal protest and actively refusing consent. By November, Ruiz had gained her freedom and with the help of her sister, Sylvia, filed a lawsuit against Judge Scott, Sonoma’s Medical Superintendent and the probation officers who conspired to have her committed and rendered infertile. In the lawsuit, Concepcion highlighted the numerous ways in which legal and institutional authorities violated her constitutional rights. She was not informed of her right to obtain legal counsel, was required to testify against herself and was summarily forced to undergo an irreversible surgery without the benefit of due process. Her life would be forever changed, and for that she demanded $150,000 in damages.

Ruiz’s lawsuit did not receive national attention like the egregiously orchestrated Supreme Court trial to sterilize Carrie Buck and uphold the constitutionality of Virginia’s eugenic sterilization law (Buck v. Bell, 1927). Nor was Ruiz’s case as widely covered as the legal battle between California heiress Ann Cooper Hewitt and her mother, who had Ann sterilized on grounds of feeblemindedness and sexual waywardness in 1936. Furthermore, the outcome of Ruiz’s lawsuit is unclear. There are no known photos of her, and little is known about her life beyond the details printed in a handful of short newspaper articles from the 1930s about her case. Yet, because Ruiz resisted sterilization and fought for justice afterwards, her story survives as an illustration of how race, gender and disability converged in the era of eugenics.

Ruiz was one of approximately 20,000 people sterilized in California institutions between the 1920s and the 1950s. Between 1907 and 1937, 32 states passed eugenic sterilization laws. California was the most prolific proponent of eugenic sterilization, performing one third of the 60,000 operations recorded nationally. Under the state’s law, passed in 1909, individuals committed to any of the 11 state institutions for the “insane” or “feebleminded” could be sterilized at the discretion of institutional authorities. While young women deemed sexually wayward like Ruiz were often targets for sterilization, almost half of the people sterilized in California institutions were young men who were declared “insane,” disabled or accused of a crime. While the law did not require consent, institutional authorities often sought signatures from parents or guardians but never from patients. If consent could not be obtained, the Medical Superintendent simply acquired permission for the operation from the Director of Institutions.

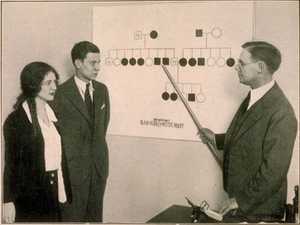

Eugenic beliefs were widespread among decision-making judges, parole officers, physicians and superintendents, who sought to prevent the reproduction of the “unfit” and were eager to play a part in creating a “better” future. Many were influenced by the esteemed California eugenicist Lewis Terman, a Stanford professor who wrote and popularized one of the most widely used intelligence tests, the Stanford-Binet. In his 1916 book, The Measurement of Intelligence, Terman, like eugenicists across the nation, declared that intelligence was not only hereditary but directly correlated to morality, crime and poverty. In order to address these social ills, he recommended institutionalization and sterilization for the “unfit.” Terman’s concepts of intelligence, heredity and fitness had distinct racial overtones. According to his studies, low intelligence was “very common among Spanish-Indian and Mexican families of the southwest and also among negroes. Their dullness seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family stocks from which they come.”

The belief that low intelligence, “feeblemindedness,” and by extension immorality, crime, and poverty were hereditary traits concentrated among people of color had serious implications for Latinos in California, especially working-class Mexican-origin women and men, who were a growing population in the state. Mexicans in California were legally considered “white,” but they were economically and socially marginalized and often cast as racially inferior foreigners, though many were born in the United States. Eugenics proponents viewed Mexicans as prone to mental defect and thus unfit to reproduce. Using IQ scores and selective family histories, Eugenicists built a medical or “scientific” language that drew on negative stereotypes of people with disabilities as immoral, criminal, incompetent, and unproductive burdens and cast Latinos as more prone to this type of supposedly hereditary defect. They also joined gendered stereotypes of Latinos—women as hypersexual and hyper-fertile and men as violent and prone to criminality—to biology and heredity. Stereotypes became “scientific truths” with grave social consequences.

During the late 19th century and into the 1920s, states established and expanded large institutions to confine the mentally, physically and socially “unfit” in order to segregate them from the public. Tens of thousands of people were warehoused in state institutions for periods ranging from days to years. Individuals who were legally committed were also deemed “incompetent,” making them susceptible to a host of treatments and procedures including sterilization. Californians across racial backgrounds were committed and sterilized in California and the majority were considered “white.” Yet, because of growing bias against Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the state, Latinos were disproportionately sterilized. Analysis of sterilization requests processed by 11 California state institutions between 1920-1945 shows that Latino men were at 23% greater risk of sterilization than non-Latino men and Latinas were at a 59% greater risk of sterilization than non-Latinas. Over 5,000 people were sterilized at Sonoma, where Concepcion Ruiz was committed. According to Sonoma sterilization records, Latino patients of both sexes represented almost 20% of all sterilizations performed between 1937 and 1948, the zenith of California’s sterilization program. According to the 1910 and 1930 census, the Mexican-origin population in the state did not exceed 6.5%.

Related Research

Despite the overwhelming power of legal officials, physicians, and superintendents to diagnose and decide the reproductive future of individuals declared “defective” or “unfit,” stories of Latino resistance, like Ruiz’s, abound. Some Latinos brought legal claims against institutional authorities. Parents and guardians often refused to sign consent forms. Others wrote letters to community leaders, priests and even the Mexican Consulate for help in preventing sterilizations. Latinos resisted in surgery rooms and even escaped from institutions. They asserted claims to civil rights in the face of eugenic efforts to classify them as unworthy and unfit.

We know so little about Concepcion Ruiz and other Latinos who were institutionalized and sterilized because available sources are largely institutional and bureaucratic, which means that they primarily tell you what eugenicists and institutional authorities thought about Latinos. Sterilization requests, for example, only mention details that justify sterilization, details like: “Mentally deficient Mexican girl, sex delinquent, had one illegitimate child.” Institutional records offer a highly reductive narrative about who the person was and why they shouldn’t reproduce. Newspaper articles about escaped patients are similar; they give very little information but just enough to get the reader to be on alert, view the escape as unjustified and suppose the escapees ought to return to the institution they fled.

These fragmentary narratives point to the long presence of Latinos in America, especially Mexican communities in the southwest. Targeted for institutionalization and sterilization in the early decades of the 20th century, Latinos asserted claims to civil rights and a will to forge futures and families. Their experiences reveal that present-day stereotypes of Latinos as criminals, rapists and social burdens in need of policing and surveillance are recycled eugenic beliefs.

Natalie Lira is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Latina/Latino Studies and Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is currently writing a book that shows how ideas about race, disability, and gender came together to shape practices of institutionalization and sterilization in California during the early to mid-20th century.

Published October 16, 2018.