Activists and the News Media

Daniel Schorr spent two decades covering the Cold War for CBS News before reporting on the Civil Rights Movement beginning in 1966. By 1974, he would become the network's chief correspondent for the Watergate scandal.

Here, the award-winning journalist recalls how the media helped dictate the messages of protesters and activists, in an era when there were only three commercial television networks and limited broadcast slots for news.

by Daniel Schorr

Access to television is competitive, but is has always been feasible for those with recognizable names, faces, and settled roles in society. For those outside the charmed circle of authority -- minorities, advocates of causes, protesters, radicals -- access to television was, at first, harder to come by, and often impossible. Impossible, that is, until they learned that television was susceptible to manipulation, if they found the right levers to press. Some groups learned by a process of trial and error that menace worked better than meekness.

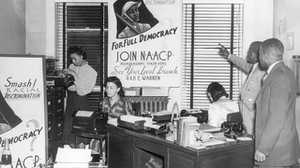

In the late 1960s, with urban unrest part of my assignment, I came slowly to realize how the television news process — from which I do not exempt myself — placed a premium on the rhetoric of violence. Black leaders who talked thoughtfully, at press conferences, about hopes and plans for peaceful change tended not to make it on the evening news; those who warned of riots and destruction often had greater success. In the rivalry of rhetoric, H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael had a decided edge over Roy Wilkins and the Reverend Andrew Young. By giving the extremists exposure, we helped to gain them support. There developed, between TV news and black extremists, a tacitly agreed mutual manipulation. To questions of "Do you think this situation is likely to lead to violence?" there were ready and willing answers. On a dull day one needed only to stake out Carmichael's store-front headquarters in the Washington ghetto, and wait to be favored with an assortment of hair-raising threats of ruination.

Just as the "ins" learned to gear their activities to media events — visually appealing episodes arranged in convenient places at times convenient for evening news deadlines — so the disinherited and the disaffected learned their own techniques for media manipulation. At first, they used demonstrations, and developed something called "guerrilla theater." The Poor People's Campaign of 1968, which Martin Luther King planned but did not live to lead into Washington, was designed as a media event. Mule carts brought the poor to an encampment called "Resurrection City" near the Lincoln Memorial. When its novelty began to fade, when its tents began to sink into the mud under dismally steady rainstorms, when television began to turn its back on this microcosm of poverty, the organizers wrote more action into the script of their guerrilla theater. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy and the Reverend Jesse Jackson led mass sit-ins in government buildings, confrontations with Cabinet secretaries, and, finally, a march up Capitol Hill to be met by police with bullhorns and predictable arrests — a sure-fire "winner" for the evening news. With Jesse Jackson as their leader, they chanted over and over again, "I am somebody!" It was an assertion of identity, and one convincing way to get confirmation of identity was to see it recognized on the evening news.

The urban riots of the 1960s presented a serious problem for television. On the one hand, the medium loves the action-packed thud of fists and policemen's clubs. There are few more exciting pictures than a fire-bombed building in living color. Networks found it difficult to resist film of riots until they were forced to take account of the effect of these pictures on the imitative and suggestible. Compelled, for once, to come to terms with its own potency, television belatedly laid down limitations on coverage of riots for fear that the epidemic would rage out of control.

From Schorr, Daniel, Clearing the Air (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), pp. 295-297.