Before the Civil Rights Movement

Journalist and author John Egerton was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1935. In his award-winning writings, which span five decades, Egerton has explored many aspects of Southern history and culture. His Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (1994) explores topics like sharecropping between the wars, the impact of World War II, and anti-Communism. In these excerpts from the book's prologue and epilogue, Egerton explains his personal relationship to the story and talks about the era.

The title of his book is taken from this 1955 quote from author William Faulkner:

"We speak now against the day when our Southern people who will resist to the last these inevitable changes in social relations, will, when they have been forced to accept what they at one time might have accepted with dignity and goodwill, will say, "Why didn't someone tell us this before? Tell us this in time?"

by John Egerton

In the August 15 [Atlanta] Constitution, under the headline CITY THUNDERS INTO POSTWAR ERA, celebrating Atlantans expressed their elation at the end of a long war (three years, eight months, and seven days, [editor Ralph] McGill reminded them) and their nervous anticipation of what lay ahead. The war had interrupted the New Deal programs aimed at rescuing the nation — and especially the South — from economic quicksand, said one observer; now it was time to face the challenges of peace.

Those challenges took many forms. The economic stimulation that the war had brought to the depressed South in the form of military bases and defense industries had to be converted to the peacetime creation of consumer goods and services. Per capita income in the region was still under four hundred dollars a year (closer to two hundred dollars for blacks), and that was barely more than half the national average.

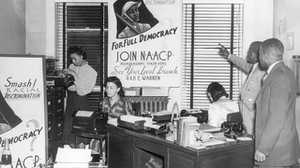

...The black thirty percent of the region's thirty million citizens were especially hungry for change; in the view of Atlanta-born Walter White, leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the victory for freedom and democracy abroad was a prelude to the battle for those ideals at home.

In the blissful aftermath of that historic conquest, the American people reached a rare state of consensus that momentarily obscured the age-old barriers between them. They were, in that fleeting instant, truly We the People, eager to from a more perfect Union, and the Southerners among them were as caught up in that contagious spirit of righteousness and invincibility as any of their countrymen.

Here surely, was a rare and momentous turning point in American history, and especially in the checkered history of the South: a crossing from darkness into light, a hinge of time swinging shut on a constricted past and opening to an expansive future. Yesterday — an almost endless ordeal of reconstruction, colonial exploitation, caste and class divisions, segregation, isolation, poverty, depression, and wartime sacrifice — was finally on the wane, if not yet altogether finished. Tomorrow — an age of opportunity, growth, prosperity, recovered self-esteem, national parity, and full citizenship — seemed ready and waiting to be born.

In the cities and towns as in the cotton fields and piney woods, the South was still caught in the paralyzing grip of the Great Depression. To make matters worse, the states were plagued with a bumper crop of political demagogues adept at turning the region's misery to their personal advantage...

...In the "separate but equal" operation of hospitals, schools, housing projects, and public transportation, whites got the lion's share of funds that were in reality pitifully inadequate for one system of services, let alone two.

...Atlanta was also a hotbed of the Ku Klux Klan, and thousands of white men (including, it was reported, a majority of the police force) belonged to the secret society as proudly as to the Masons or the Shriners or the Rotary — looked upon it, in fact, as a charitable organization dedicated to the perpetuation of Victorian morality and white Protestant supremacy, two of the prevailing dogmas of the time.

...Against these currents of reaction, Mayor James L. Key battled to make progressive improvements... I knew none of this, of course, being only an infant at the time.

Television was coming, and jet airplanes, and air-conditioning, and a sparkling showcase of consumer goods, from high-powered V-8 Fords and Chevrolets to electric "iceboxes" with inside lights, and nylon hose with seams up the back.

...The South had a multitude of chronic ills — Mr. Roosevelt himself had called the region in 1938 "the Nation's No.1 economic problem" — but its people, white and black, looked to the postwar period as the long-awaited time of salvation and redemption, the time when second-class citizenship would finally end. At long last, the South had a future worth striving for.

One of the things I have come to see in retrospect is how favorable the conditions were for substantive social change in the four or five years right after World War II. It appears to have been the last and best time — perhaps the only time — when the South might have moved boldly and decisively to heal itself, to fix its own social wagon voluntarily. But it didn't act, and the moment passed, and all that has happened in the tumultuous decades since — the federal court decisions, the minority quest for civil rights, the actions of presidents and congressional bodies, of governors and legislatures, of mayors and city councils and law-enforcement officials — has followed from that inability to seize the time and do the right thing, not simply because it was right, but because it was also in our own best interest.

...in 1932, a political initiative launched in response to a desperate economic crisis brought hope to a beleaguered populace mired in colonial dependency. At the end, in 1954, a union of two hallowed American constitutional principles — equal justice under the law and the right of citizens to petition their government for a redress of grievances — brought to robust life a movement toward freedom that now, forty years later, still energizes people and nations around the world.

... [After the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision,] public opinion in the South was mixed but cautiously moderate, even quietly hopeful. In only four states — Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia — were bluntly hostile and defiant words spoken by senators and governors in response to the Brown ruling, and even a few of them showed some respect for "the edict of the court."

...In Atlanta, the Southern Regional Council, feeling vindicated and invigorated by the court's action, looked ahead to an era of growth and progress. In Nashville, a grant from the Ford Foundation's Fund for the Advancement of Education allowed a board of educators and newspaper editors to organize the Southern Education Reporting Service, an independent agency to monitor and document the school desegregation process.

But these tiny shoots of new growth heralded a false spring. The white South could perhaps have been persuaded to obey the law of the land, but it lacked the voices of responsible leadership to ensure that outcome...

...Governors, legislators, city and county politicians, and state and local school officials fell dutifully, often enthusiastically, in line with the Washington-based advocates of white power. Businessmen sounded the alarm, and labor officials echoed it. The bar associations of almost every Southern state and city failed to speak out in defense of the rule of law, and some even went so far as to condemn the Supreme Court and defy its ruling. With each passing day, more and more ministers and academicians and editors who dared to affirm the integrity of federal judiciary were ostracized and silenced.

The Washington journalist I. F. Stone summed up this latest manifestation of the America dilemma:

There is a sickness in the South... To the outside world it must look as if the conscience of white America has been silenced, and the appearance is not too deceiving. Basically all of us whites, North and South, acquiesce in white supremacy, and benefit from the pool of cheap labor created by it....The American Negro needs a Gandhi to lead him, and we need the American Negro to lead us.

Two months later, in Montgomery, Alabama, a black Gandhi with a voice like Southern thunder answered the call.

From Egerton, John, Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), pp. 10-11, 615-618, 623.