People Of The Civil Rights Movement: Part 2

Malcolm X (1925-1965)

A street hustler who became a black nationalist leader, Malcolm Xconverted to Islam while in prison. Born Malcolm Little to parents active in Marcus Garvey's movement, Malcolm rejected "Little" as a family name given to him by an ancestral slave owner. After his 1952 release from prison, he joined the Nation of Islam (NOI) in Detroit, trained personally under its leader Elijah Muhammad, and became a minister. Malcolm X organized NOI temples, developed the organization's newspaper, and was named its national spokesman. Malcolm X offered an alternative to Martin Luther King, Jr., refusing to endorse non-violence and telling black audiences their goal should be separation from white society, not integration into it.

Malcolm's fiery comments and growing popularity led to an estrangement from the NOI leadership. Increasingly, Malcolm X rethought his politics, becoming attuned to the black freedom movement and liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Towards the end of his life, Malcolm became involved with a militant wing of the U.S. freedom movement, including leaders like Fannie Lou Hamer and Gloria Richardson; and he insisted the fight for equality was a human rights struggle. He called for a united front with leaders such as James Farmer of CORE and Martin Luther King Jr., and journeyed to Selma, Alabama to speak in support of Dr. King in February 1965. Malcolm X was assassinated by members of the NOI in New York City just a few weeks later.

Rhody McCoy (1924-?)

Born and educated in Washington, DC, Rhody McCoy graduated from Howard University and New York University, before teaching in New York for 18 years and becoming an acting principal. He was chosen to serve as superintendent of the Ocean-Brownville school district in 1967. An experiment in school decentralization, the district was to be run by a governing board with more representation from parents and community organizations. The teacher's union fought McCoy's efforts to bring in three new principals of color and remove 19 teachers and administrators, calling a strike in September 1968. Amid mounting tensions and allegations of anti-Semitism by the district, the New York Board of Education rescinded McCoy's decisions and disbanded the governing board.

Arthur McDuffie (1946-1979)

Arthur McDuffie was an African American Marine Corps veteran and insurance salesman savagely beaten by white Miami policemen during a traffic stop in December 1979; he died four days later. Four officers were tried in Tampa by prosecutors from the office of future Attorney General Janet Reno, and acquitted by an all-white jury in May 1980. Miami's African American community, already frustrated by a lack of economic opportunity and a sense of being passed over in favor of Hispanic immigrants, was outraged. The night the verdict was announced, riots erupted in the section of Miami known as Liberty City; 18 people died.

James Meredith (1933-)

In September 1962, Air Force veteran James Meredith, armed with a federal court order, attempted to register for classes at the previously all-white University of Mississippi. Blocked by state officials and violent mobs, Meredith was only able to enroll after the Kennedy administration sent in federal troops and marshals. Meredith graduated in 1963, and in June 1966, he began a "march against fear" from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. After segregationists shot and wounded Meredith during his march, CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC took up the march, which was successfully completed later that month. Meredith later got a law degree from Columbia University and worked for conservative North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms.

Mamie Till Mobley (1921-2003)

After Emmett Till's murder, his 33-year-old mother Mamie made sure that the world knew what had been done to her son, insisting on an open-casket funeral that thousands attended in Chicago. A picture of Emmett's disfigured corpse appeared in Jet magazine. African Americans across the country were outraged by the sight -- and the speedy acquittal of Emmett's murderers. Mamie lectured about her son's killing across the country, helping spur increased membership in the NAACP. Her public presentation of this dramatic case helped lay the groundwork of changes in national public opinion and fostered the awakening of a new generation of civil rights workers. She would go on to teach for 25 years in the Chicago public school system.

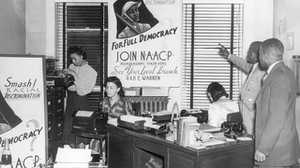

Constance Baker Motley (1921-2005) and Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993)

Thurgood Marshall was only 30 years old when he replaced his former professor Charles Houston as special counsel for the NAACP in the late 1930s. In that era, the NAACP was considered a radical left-wing organization. Under Marshall's leadership, the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund took aim against segregation, winning the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing segregated schools in 1954, the 1956 Browder v. Gaylelawsuit that abolished segregation on Alabama buses, and the 1955 case admitting Autherine Lucy to the University of Alabama (though the University later found a way to avoid admitting Lucy).

Marshall's colleague Constance Baker Motley helped write the legal brief for Brown and took the lead in the 1962 Meredith v. Fair lawsuit that won James Meredith's admission to the University of Mississippi. Both NAACP lawyers achieved significant "firsts": Motley was the first African American woman appointed to the federal judiciary, and Marshall rose to become the nation's first black Supreme Court justice.

Diane Nash (1938-)

A Chicago native who had never experienced segregation in public accommodations before moving to the South, Diane Nash first attended workshops on nonviolence as a student at Nashville's Fisk University. Along with John Lewis, she formed the Nashville Student Movement, which aimed to desegregate the city's lunch counters. Nash organized the sit-ins that began there in 1960, eliciting a televised admission from Mayor Ben West that segregation was wrong. Nash participated in the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and picked the group of students from Nashville who joined the 1961 Freedom Riders. Nash later became active in the antiwar movement.

Huey Newton (1942-1989)

Named for populist Louisiana politician Huey Long, Huey P. Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with college friend Bobby Seale in October 1966. Newton, who was attending law school and was well versed in constitutional rights, became the party's minister of defense and participated in monitoring an Oakland police force notorious for its brutality towards African Americans. Newton would be shot in the stomach by those he dubbed "pigs" early in the morning of October 28, 1967, and tried for murder in the death of a police officer. The resulting "Free Huey" movement was successful; Newton's manslaughter conviction was overturned and he was released in 1970. At its zenith Newton's Black Panther Party ran a phenomenal number of community programs providing free breakfast, clothing, shoes, housing, health, education, job training and legal aid to people in need. Newton's life ended in violence; an Oakland drug dealer gunned him down in 1989.

Rosa Parks (1913-2005)

On December 1, 1955, at the age of 43, Rosa Parks, a civil rights activist who worked as a seamstress, refused to vacate her seat for a white passenger on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. That state imposed Jim Crow segregation laws, and Parks was arrested. In response, the leader of the Women's Political Council, a local English professor named Jo Ann Robinson, and E. D. Nixon, a former Garveyite and a president of both the local Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the local NAACP branch, helped organize a mass bus boycott by the black working people of Montgomery, especially female domestic workers. The boycott lasted for 381 days, until the Supreme Court struck down the bus segregation law. It also brought a young local minister named Martin Luther King, Jr. to national attention. Fired from her job, Parks moved to Detroit and found work with a Michigan Congressman. After Parks died in 2005, she was the first woman to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

James Earl Ray (1928-1998)

In spring 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. went to Memphis to support striking black sanitation workers. On April 3, his standard speech came with a new ending: "I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land." The next night, King was shot outside of his motel, and died in hospital. Two months later, a white American named James Earl Ray was arrested in London and extradited to the United States. Ray confessed to the murder but later recanted his confession. Aside from three days as an escapee, Ray spent the rest of his life in prison. Some, including members of King's family, have questioned whether Ray was involved in the death of King or whether conspiracies remain to be uncovered.

Ronald Reagan (1911-2004)

Ronald Reagan, one of the most popular politicians in recent history, embodied the American conservative movement of the late 20th century. However, many people found his conservative ideals directly opposed to programs that benefited minority groups.

As governor of California (1967-1975), Reagan clashed with activists like the Black Panthers in Oakland, and encouraged the firing of University of California professor Angela Davis. In the presidential campaign of 1980, he invoked "states' rights" which some heard as a code phrase for racism. As America's 40th president (1981-1989), he tried to eliminate the Department of Education and cut back on loan and assistance programs that helped underprivileged students get a leg up. Throughout his political career, Reagan undercut anti-poverty programs and urban assistance while cutting taxes, widening the gap between rich and poor. In support of business, his administration failed to enforce the Community Reinvestment Act, which outlaws racial discrimination in home loans, and made many federal contractors exempt from Affirmative Action programs.

However, during his presidency, Ronald Reagan signed the bill that declared the third Monday in January a national holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bobby Seale (1936-)

Bobby Seale, an Air Force veteran and standup comedian, worked for years in student and community politics in the San Francisco Bay area. He was a member of the Afro-American Association, the Soul Student Advisory Council, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, the NAACP, and the Revolutionary Action Movement. In the aftermath of a race riot involving police brutality in September 1966, Seale, then working at an Oakland anti-poverty center, co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with Huey Newton, taking the panther symbol from the Lowndes Country Freedom Organization that Stokely Carmichaelhad helped create.

Seale served as the Black Panthers' first chairman and took part in a May 1967 demonstration of the right to carry weapons at the California state legislature, for which he was arrested. He was also charged with conspiracy to incite riots as member of the "Chicago Eight" and was imprisoned for contempt of court; all charges were eventually dropped. Seale was known for his Black Power oratory with its distinct wit and imaginative humor. While Newton was in prison, Seale led the Black Panther Party from a local movement into a national organization with branches across the United States and affiliates in other countries.

Seale participated briefly in the negotiations over the Attica prison takeover in 1971 and unsuccessfully ran for mayor of Oakland in 1973. He left the Black Panther Party in 1974.

Frank "Big Black" Smith (1933-2004)

Frank Smith, who weighed 250 pounds and stood over six feet tall, served nine years in prison for robbery. In 1971 he was in New York's Attica state prison when the prisoners revolted. A charismatic man popular with inmates and prison staff, Smith guarded the negotiators sent in to settle the standoff. After state police retook the prison by force, the police meted out fierce retribution. Barefoot prisoners were made to run through broken glass while police beat them with clubs. Smith was stripped naked, his testicles were beaten, cigarettes were put out on his skin, and he was ordered to remain motionless with a football held under his chin or he would be killed. In 1974, Smith was released from prison and worked as a paralegal investigator. In 2000, Smith and about 800 other plaintiffs won an $8 million settlement against New York State; the judge singled out Smith as "a real peacemaker in the Christian sense." "Getting the money is not the whole thing," Smith said, "it's about getting justice and having the state admit that it was wrong."

Carl Stokes (1927-1996)

Former prosecutor and Ohio state representative Carl Stokes narrowly lost Cleveland's mayoral election in 1965 but tried again two years later. Unlike Richard Hatcher, running simultaneously in Gary, Indiana, Stokes was seeking office in a majority white city, and he tried not to alienate those voters. He went so far as to ask Martin Luther King, Jr., whom Stokes greatly admired, not to conduct marches in Cleveland during the campaign. "It came down to the hard game of politics," he said, "whether we wanted a cause or a victory. I wanted to win." He did win, defeating Republican Seth Taft and becoming the first black mayor of a major American city. Stokes was in office for two terms and later served as a news anchor, judge, and U.S. ambassador.

Emmett Till (1941-1955)

Raised in Chicago, Emmett Till was just 14 in August 1955 when he went to visit his great uncle Moses Wright in Mississippi. On his fourth day there, Till allegedly whistled at a white woman. A few nights later, the woman's husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother J. W. Milam kidnapped and then brutally murdered Emmett, tying his body to a 75-pound cotton gin fan and then tossing it in a river. Despite testimony from Wright, the killers were acquitted by an all-white jury. But Till's murder and his mother Mamie's decision to have an open-casket funeral galvanized the African-American community, including the NAACP and its Mississippi field secretary Medgar Evers.

Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael)(1941-1998)

Trinidad native Stokely Carmichael moved to New York at age 11 and later graduated from Howard University. He joined SNCCand participated in voter registration efforts in Mississippi and Alabama in the mid-1960s, helping form an independent black political group, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. While helping complete James Meredith's 1966 "march against fear," Carmichael issued the first call for "black power." Taking over the chairmanship of SNCC from John Lewis, Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture to reflect his African heritage and distanced himself from the civil rights movement's earlier commitment to nonviolence, making common cause with the Black Panther Party in 1968.

Ben West (1911-1974)

When sit-ins aimed at desegregating Nashville's lunch counters began in February 1960, the city's mayor, Ben West, was angry with the students leading them. The sit-ins were seriously hurting business downtown. But West's attitude changed when sit-in opponents turned to violence, blowing up the home of an attorney who had defended the students in court. Later that same day, 2,500 students marched to city hall. When questioned there by student leader Diane Nash, West said it was wrong to refuse someone service because of his or her race. The next day's Nashville Tennessean headline read, "Mayor Says Integrate Counters," and within three weeks the voluntary desegregation of those counters had begun.