Politics and the March on Washington

The son of Alabama sharecroppers, John Lewis became a major leader in the civil rights movement, and later a representative from Georgia in the U.S. Congress, where he still serves. He participated in seminal events including the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and the Selma-to-Montgomery march. As chair of SNCC he coordinated voter registration and community activities of Freedom Summer in Mississippi. Deeply involved in the planning of the 1963 March on Washington, Lewis at age 23 was one of the day's keynote speakers, delivering an address that was carefully calibrated by his colleagues to avoid inflammatory rhetoric. Here Lewis describes the process of editing that speech.

by John Lewis

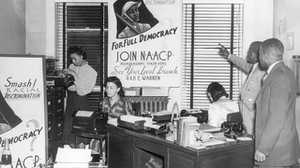

During the early discussions about the march, it was never our design to come to Washington to support any particular piece of civil rights legislation. But before the march, by the time we got to Washington, some of the people, particularly the representatives of the Urban League, the NAACP, and maybe a segment of organized labor, wanted the march to support proposed legislation. We in SNCC took exception to that. In one part of the speech I had prepared with my colleagues, I suggested that we could not support the Kennedy legislation because it did not guarantee the right of black people to vote. President Kennedy and his administration took the position that if you had a sixth-grade education you should be considered literate and then you should be able to register to vote. We disagreed with that; we felt that the southern states had denied people a right to a decent education and now it's wrong for them to come back and say you must be able to pass a literacy test in order to be able to register to vote. SNCC, and I think the southern wing of the movement, took the position that the only qualification for being able to register to vote should be that of age and residence.

During the time leading up to the preparation of my speech, there was an article in the New York Times with a picture of a group of women in Rhodesia who had signs saying, "One man, one vote." In my speech I said something like, "One man, one vote, is the African cry. It must be ours too." Some of the people objected to that.

In another part of the speech we suggested that there was very little difference between the major political parties, that the party of [moderate Republican Senator Jacob] Javits is the party of [conservative Republican Senator Barry] Goldwater, that the party of Kennedy is the party of [segregationist Democratic Senator James] Eastland. Then I raised the question, "Where is ourparty?" I suggested that as a movement we could not wait on the president, on members of the Congress, we had to take matters into our own hands, and I went on to say that the day might come when we would not confine our marching to Washington, that we might be forced to march through the South the way [Union general William Tecumseh] Sherman did, [but] nonviolently. Some people suggested that was inflammatory, that it would call people to riot, and you shouldn't use that type of language.

From Hampton, Henry, and Steve Fayer, Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s (New York: Bantam Books, 1990), pp. 165-166.