In 1921, the American Relief Association sent food aid to Russia, where millions of citizens were suffering from a devastating famine. Browse this gallery of the human story -- see the Russians who endured and the Americans tasked with delivering salvation.

-

As food supplies dwindled in 1921, many families became refugees in hopes of finding food and help elsewhere. Here a group of adults and children huddle together.

Credit: David King Collection -

The American Relief Administration's goal in Russia was to do what it had done in postwar Europe -- feed children like these in Tsaritsyn (Volgograd). Feeding one million seemed a manageable task, but soon after they started, the ARA realized the need was far greater.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

A family stands somberly next to their dying horse, their belongings beside them. During the famine service animals like this one died, leaving people in search of food stranded.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

Retired Army officer William Haskell (right) served as the ARA's director of relief operations in Russia. His carefully crafted communications with Herbert Hoover helped secure more funding from the U.S. Congress and helped boost cooperation from the Soviet government.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

George McClintock (left) fills a citizen's bag with food while hundreds of others wait in line. A reported 25 million Russian and Soviet citizens were affected by the famine.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

Felix Dzerzhinsky (front, center) signs paperwork. Dzerzhinsky was the first head of the Cheka, the communist secret police, which temporarily diverted food supplies to favored associates.

Credit: David King Collection -

Russian women and children travel to Ufa, southeast of Moscow, to seek refuge. The ARA was unable to provide enough food for the roughly nine million residents in the Ufa-Urals district, so committees of local citizens decided who would be fed.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

Three women at Vechorova, a village east of Moscow, stand in front of a train on their way to Volga. Due to the scarcity of horses and efficient transportation, women and children were forced to deliver large heavy sacks of grain and food to their towns and families by foot.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

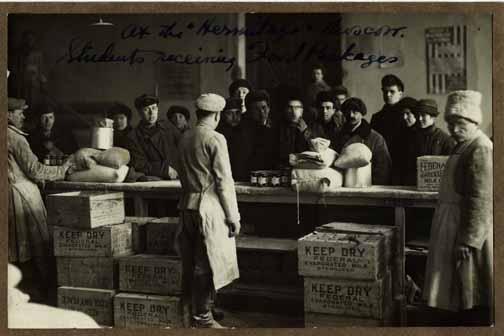

The ARA set up kitchens near school campuses so students would not go hungry. Here, students receive food packages at the Hermitage, Moscow.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

A doctor inoculates citizens in Petrograd. During the famine, many Russians crowded into unsanitary shelters, where lice often spread typhus and other diseases.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

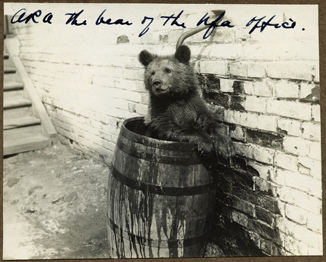

Colonel Walter L. Bell kept a pet bear at the ARA's Ufa office. The animal served as an entertainer and companion for Bell and his colleagues.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

The ARA received an extra $20 million from the United States government, so it could purchase more grain. In 1922 the ARA was feeding up to 11 million citizens a day in kitchens such as these.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

During his time in the area, Colonel Walter Bell built a special relationship with the local Muslim leaders. When the famine ended, Ufa's holy men showed Bell their ancient copy of the Koran, marking the first time the prized relic had been shared with a non-Muslim.

Credit: Hoover Institution -

Here four children enjoy a meal outside a kitchen in a former Hermitage restaurant in Moscow. With the famine over in 1923, the ARA wrapped up its work in the USSR.

Credit: Hoover Institution