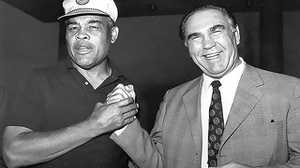

Joe Jacobs (1898-1939)

The boxing manager Joe Jacobs, born in New York's East Side before the turn of the century, was the son of Hungarian Jews. In his most famous client's description, he "spoke a mishmash of English and Hungarian as if he had just stepped off the boat. He knew nothing about boxing, but he knew how to negotiate and get his man the best deal possible. And he was as nice as he was clever."

"I received a letter from the Reich Ministry of Sports. They want me to split from Joe Jacobs, my manager since 1928.... I really need Joe Jacobs. I owe all my success in America to him." — Max Schmeling to Adolf Hitler, 1935

Local Connections

Andre Routis, a boxer in Jacobs' stable, introduced Jacobs to max Schmeling. Schmeling had a contract with Arthur Bülow, but Bülow, a fellow German, did not know the American scene and Schmeling realized he needed someone with local connections. In switching managers, Schmeling ran afoul of boxing authorities, but Jacobs graciously agreed to forego his own fees and let Bülow collect his percentage for the remainder of Bülow's contract with Schmeling.

Energetic Promoter

Jacobs set to work, inventing a ridiculous nickname -- "The Black Uhlan of the Rhine" -- for his new fighter, arranging fights and endlessly promoting him: "You need publicity. Not a single day can go by without your name being in the papers." Jacobs arranged for Schmeling to be photographed on skyscrapers, with politicians and at parties. Schmeling managed to make the socializing unnecessary with his performances in the ring; after a string of victories, boxing fans knew his name quite well.

Canny Investment

After Schmeling's introduction to the American boxing scene, Jacobs, Schmeling and his trainer Max Machon traveled to Germany, triumphant. On the trip, Jacobs discovered a lucrative side business. Prohibition had inflated the black market price of a bottle of champagne to $50, and when Jacobs saw that a shipboard bottle cost only $3, he bought the ship's entire stock — 20,000 bottles.

P.R. Success

Jacobs was an unstoppable public relations dynamo. For Christmas in 1929, Jacobs rented a hall in one of Berlin's working class neighborhoods. There Schmeling and Jacobs fulfilled the wishes of a few hundred children who came to visit. In his memoirs, Schmeling writes, "What moved me most was the modesty of their requests: usually a few crayons, a top, a pencil case, or a bathing suit... I was especially touched by a five-year-old girl... whose wish — that her father stop drinking — we couldn't fill. But the idea was a great success, and Joe Jacobs came up to me afterwards and asked, 'How did we do that?' For once, he took the giant cigar out of his mouth."

A Title for His Charge

For Schmeling's 1930 championship bout against Jack Sharkey, Jacobs had arranged to donate a portion of ticket sales to the Hearst Milk Fund, a favorite charity of the wealthy publishing family, guaranteeing coverage by the Hearst newspapers. Schmeling won the heavyweight championship by default after Jack Sharkey was disqualified for hitting below the waist. It was not how Schmeling had imagined claiming the title; in fact, it would be the only time the championship was decided on a foul. Jacobs had to cheer his boxer up afterwards, as the public began calling Schmeling the "low-blow champion." "Defend the title in your next fights! Then you can show them whether you deserve it or not!"

The Rematch

The two boxers met again in 1932 for another title fight. After Sharkey won a controversial decision in the rematch, Joe Jacobs uttered his most famous line: "We was robbed!" He went on, "They stole the title from us!"

A Jew's Salute

Jacobs went to Germany for Schmeling's 1935 fight against Steve Hamas in Hamburg. Ever since Adolf Hitler's rise to Chancellor in 1933, Germany had been swept up in a militant nationalism, and anti-Semitism was on the rise. Immediately after Schmeling won the fight, the 25,000 spectators spontaneously stood and sang the Nazi anthem with hands raised in the Nazi salute. Schmeling recalled that Jacobs, congratulating his fighter in the ring, didn't seem to know what to do. Then he raised his right hand, with its omnipresent Havana cigar, and joined the salute. "After a few seconds he turned to me and winked." The scene did not go over well with the Nazi brass. As writer David Margolick explains, "It was a moment of high Wagnerian pageantry... It made the Nazis unhappy because here was this Jew giving the Nazi salute and not only that, he had a cigar in his hand, which they thought was a terrible impertinence."

Political Fallout

Photographs of a saluting Jew smiling ironically with cigar in hand were published around the world. Back in the U.S., they caused outrage. In the New York Daily News, Jack Miley wrote, "Up in the Bronx the good burghers agreed that the little man with the big cigar was no credit to their creed. in the Broadway delicatessens and nighteries... the waiters were conspiring to slip Mickey Finns in his herring." The German Minister of Sports called Schmeling and insisted that the boxer spend more time in Germany, with German associates. Schmeling had no intention of giving up Jacobs and asked Adolf Hitler for an audience. Hitler received Schmeling and ostentatiously ignored the fighter, making small talk with his actress wife instead. Schmeling got the message and chose to emulate the Führer by ignoring the Sports Minister's entreaties.

Suspended

Unwelcome in Germany, Jacobs continued to work hard for his fighter in America. He arranged a fight with Joe Louis, but backroom deals kept him from arranging a title shot against Jimmy Braddock. Once Louis became champion, Schmeling was granted a rematch — but the Boxing Commission had temporarily suspended Jacobs for one of his public relations stunts. Jacobs had had one of his fighters, Tony "The Walking Beer Barrel" Galento, photographed with a keg in the ring. The terms of Jacobs' suspension prevented him from sitting in Schmeling's corner or even visiting his locker room. Schmeling mentions Jacobs' absence as one of the factors contributing to his nervousness before the fight, and he lost quickly to the revenge-hungry Louis.

"He Made Us Laugh"

In 1939 Jacobs died of a heart attack, at the age of forty-one. Although others blamed the cigars and alcohol, Schmeling considered Jacobs a victim of his own character. "How often had he made us laugh with his constant state of excitement -- gesticulating, voice cracking, never finishing a sentence, working on his cigar, gasping for breath. That's what Joe Jacobs died of."