Joe Louis (1914-1981)

"Joe Louis is the hardest puncher that I've ever seen... He's a good man. Anyone who plans on beating him had better know what they're doing."— Max Schmeling, before the first Louis-Schmeling fight

Joe Louis Barrow was born on May 13, 1914, in Alabama, the seventh of eight children, a grandson of slaves and one quarter Cherokee. When the boy was just two years old, his father, Munroe Barrow, was committed to an asylum. His mother Lily, a religious woman, worked hard and raised her children to have manners. She married again, to a widower named Pat Brooks with eight children of his own. Looking for a better life, Pat and Lily followed the path of many southern black families, and moved their new family up to Detroit, where factory work was plentiful.

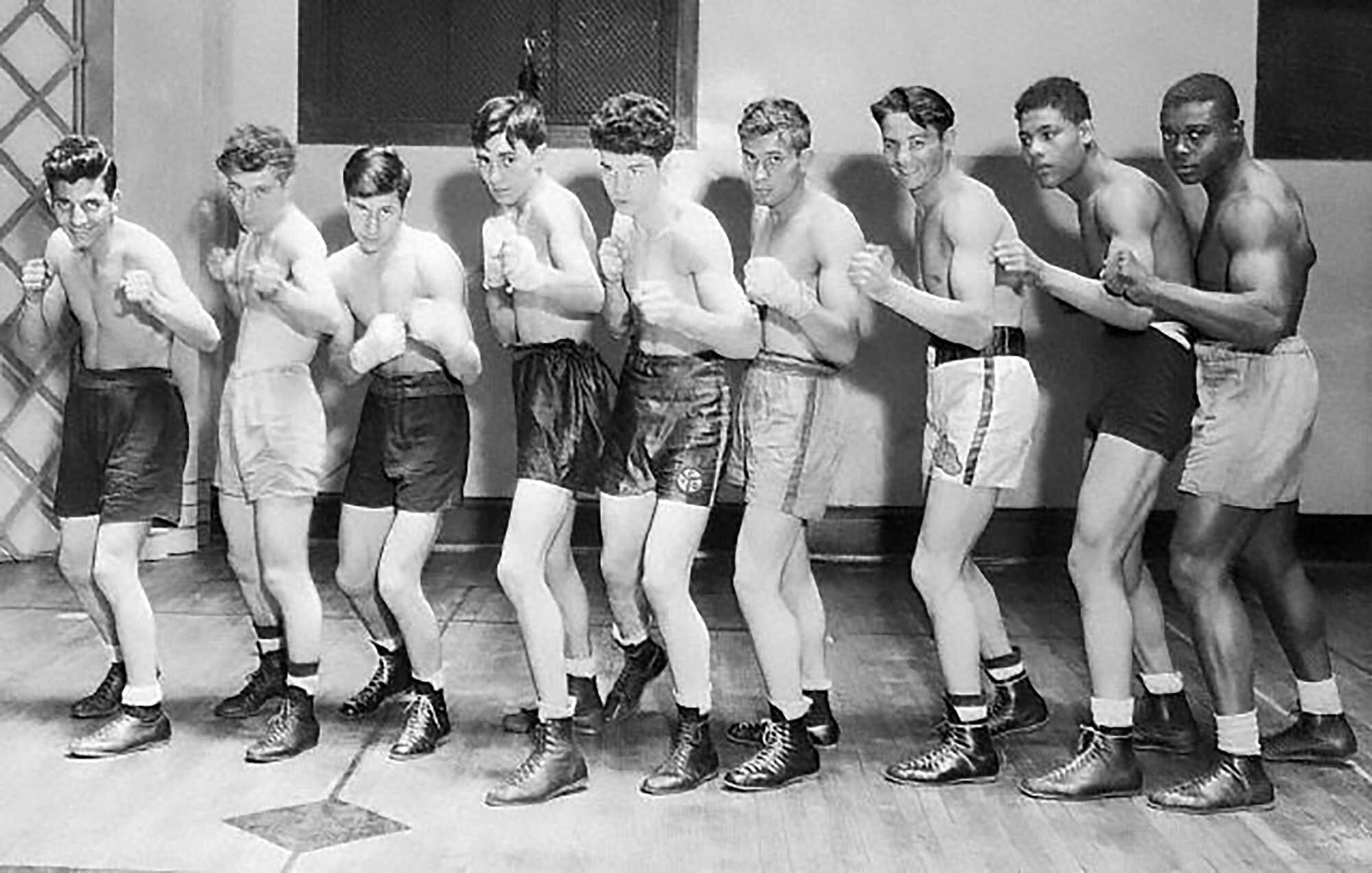

Shy Boy

Joe was shy, quiet, and uninterested in school, and so was often mistaken for being dumb. A friend took him to Brewster's East Side Gymnasium and introduced him to boxing. He fell in love with the sport. He shortened his name to Joe Louis so that his mother wouldn't find out, but she caught on eventually. "At first [Momma] looked unhappy," Louis recalled. "But she said that if any of us kids wanted to do something bad enough, she'd try to see that we got a chance at it. 'No matter what you do,' she said, 'remember you're from a Christian family, and always act that way." It was in the early days of the Depression, and his stepfather and mother accepted the $7 checks Louis brought home.

Big Purses

Louis' success in Detroit's amateur boxing tournaments drew the attention of John Roxborough who became his lifelong manager. Roxborough enlisted a friend from Chicago, Julian Black, who had some experience promoting fighters, and they hired Jack Blackburn as a trainer. Louis kayoed Jack Kracken in his first professional fight on July 4, 1934. Through the end of 1935, he earned $371,645 in professional purses --about 300 times the average annual salary.

A Young Comer

The heavyweight championship was in reach, as long as Louis' team could secure a fight with James J. Braddock, the title holder in 1935. The path required that Louis beat other contenders for the title to prove himself a worthy opponent, and to demonstrate that his name could sell tickets. As boxing historian Herb Goldman described this period, "Louis was going through the heavyweight division like Sherman through Georgia." He took Max Baer in four rounds; Primo Carnera in six. Former heavyweight champion Max Schmeling was on the same path to reclaim his title. The Schmeling and Louis camps agreed to a bout in 1936, with a contract providing that they would not schedule any other fights for six months beforehand. In the interim, Louis took up golf. His remarkable record of victories had bred complacency.

An Idol Falls

Louis had won his first 27 professional bouts, 23 by knockout -- and was the 10-1 favorite in the fight against Schmeling. Yet Schmeling stunned Louis and American fight fans with a knockout in the 12th round. "An idol fell," wrote the New York Post, "and the crashing was so complete, so dreadful and so totally unexpected that it broke the hearts of ther Negroes of the world." Louis' friend Walter Smith would recall, "Everybody was sick. Usually after Joe Louis got through fighting, everybody would be out in the streets, driving, honking their horns... And not only in Detroit. Philadelphia, New York and Chicago, everywhere. Not that night, no... it was a sad night... it was like a funeral."

Renewed Purpose

After his first professional loss, Louis returned to training with a renewed purpose -- to defeat Schmeling. Schmeling and Braddock had arranged a title match, but as Adolf Hitler made headlines and threatened war, anti-Nazi groups and unions promised a boycott, scaring off the promoter. Braddock's management found they could make more money with less controversy by setting up a match with Louis. In fact, they were promised 10% of Louis' earnings for the next ten years, a tidy sum. On a knockout in the eighth round, Louis became the new heavyweight champion of the world. But it was not until his 1938 rematch against Schmeling, when he quickly knocked out the German boxer, that Louis truly felt like the undisputed champion.

Patriot and Morale Booster

Louis held the world heavyweight title for 12 years, through 24 bouts, longer than anyone before or since. When the United States entered World War II, Louis enlisted in the Army. "Might be a lot wrong with America but nothing Hitler can fix," he said. He fought exhibition matches to raise money for the Armed Services and boost morale for the troops. He made donations to military relief funds. Historian Jeffrey Sammons says, "Joe Louis set a stunning example through his acts of patriotism, and even the South responded appreciatively."

Penniless Champion

In 1949, Louis retired as the undefeated champion. He made a failed comeback attempt a few years later, in large part because of an enormous tax bill. He had always been generous to his family, paying for homes, cars and education for his parents and siblings. He was magnanimous to strangers, too, handing out $20 bills to anyone who asked. He invested in a number of businesses -- the Joe Louis Restaurant, the Joe Louis Insurance Company, a softball team called the Brown Bombers, Joe Louis Milk Company, Joe Louis Punch (a drink), the Louis-Rower P.R. firm, a horse farm and more. All eventually failed. He gave liberally to the government as well, paying back the city of Detroit for any welfare money his family had received, and donating huge sums earned from his exhibition boxing to the war effort. Despite all the money he had made, Louis, like most other boxers, did little to protect himself financially, and wound up owing a tremendous amount of back taxes. As he would later put it, "When I was boxing I made five million and wound up broke, owing the government a million. If I was boxing today I'd make ten million and wind up broke, owing the government two million."

Women and Children

Louis' personal life was as active as his professional life. He married Marva Trotter just hours before his fight with Max Baer in 1935. They divorced and remarried and were divorced again in 1948. In 1955 Louis married Rose Morgan, a successful Harlem businesswoman; their marriage was annulled in 1958. In 1959 he married an attorney, Martha Jefferson. He had affairs with celebirities like Lena Horne, Sonja Henie, and Lana Turner, and dalliances with showgirls and other women. His managers had warned him against being seen with white women for fear that it would taint his reputation; from this Louis had learned discretion. He fathered two children with Marva — Jacqueline and Joe Louis Barrow, Jr.— and adopted three more children.

Comfortable Old Age

Toward the end of his life, Louis took a job as a greeter for a Las Vegas casino. The government agreed not to collect on the back taxes, and he lived comfortably among friends. He died on April 12, 1981. President Ronald Reagan allowed Louis to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery with military honors. At the end of his memoir, Louis wrote, "I almost always did exactly what I wanted to do."