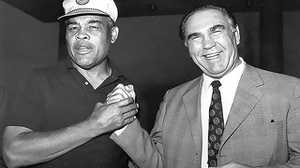

John Roxborough and Julian Black

"Roxborough and Black took care of the reporters. They told them that Schmeling got me with a 'Sunday punch' in the second round, but even with that, it took him ten rounds to take me out." — Joe Louis on the first Schmeling fight.

Young Joe Louis was fighting in Golden Gloves tournaments in Detroit when he was introduced to John Roxborough. A former basketball player, Roxborough had begun his business career as a bail bondsman. By the time he met Louis, Roxborough ran a real estate office that served as a front for his numbers operation, a popular but illegal form of private lottery. A generous and nattily dressed man who supported promising athletes and students in the neighborhood (and had a state senator for a brother) Roxborough appeared to Louis as "well encased in dignity and legitimacy." Roxborough saw in Louis the chance to make big money.

Manager's Sales Pitch

In his autobiography Louis would recall, "[Roxborough] told me about the fate of most black fighters, ones with white managers, who wound up burned-out and broke before they reached their prime. The white managers were not interested in the men they were handling but in the money they could make from them. They didn't take the proper time to see that their fighters had a proper training, that they lived comfortably, or ate well, or had some pocket change. Mr. Roxborough was talking about Black Power before it became popular."

An Example

Louis took on Roxborough as his manager. Roxborough paid for Louis' gloves and equipment, and even gave him some shirts and ties. Roxy's upper middle class life gave Louis a powerful example. As part of Louis' development, Roxborough devised a list of commandments designed to keep the young fighter from becoming like Jack Johnson, the only previous black heavyweight champion, whose flagrant disregard for the racial barriers of the day had shocked and disturbed the public. Two of the rules were never to be photographed with a white woman, and never to gloat over a defeated opponent.

Well-Connected Partner

In 1934, as Louis turned professional, Roxborough brought in another partner, Julian Black. Black was a numbers man in Chicago who had helped Roxborough through a rough patch. More importantly, Black had a stable of fighters in Chicago and was set up to launch Louis' career.

Contractual Terms

Just after he turned 21, Louis signed a ten-year contract with Black. The terms stated that twenty-five percent of the boxer's earnings from the purse, as well as half of all movie and radio broadcast profits, would go to his managers. Roxborough held another contract for twenty-five percent, for an indefinite period.

Pressure from Whites

His new managers hired Jack Blackburn as Louis' trainer and worked hard to schedule fights for their charge. The two men constantly felt pressure from the white establishment to relinquish their management of Louis. The Michigan state boxing commissioner asked them to take on a white co-manager or else forget about fighting in the state again. Roxborough would not back down.

Tough World

In New York, James J. Johnston of Madison Square Garden refused to let Louis fight in his arena on economic grounds: he didn't think a black fighter would sell tickets. But Louis' success opened up most venues to him and demonstrated that he could put fans in the seats. Prior to Louis' title fight against James Braddock, Braddock's manager had some goons pick up Roxborough on the street and drive him around town before finally delivering him to the manager's office. Roxborough was scared out of his wits, but when a deal to co-manage Louis with the white promoter was offered, he stood his ground. "You need us more than we need you. Joe can always make a buck and Braddock can't," he said, and walked out.

Finding the Right Connections

A deal with another white man would prove impossible to resist. In 1935, Mike Jacobs, one of boxing's biggest promoters, stepped in to handle Louis. Jacobs' skin color, savvy, and connection to the powerful Hearst family made what had been near impossible for Roxborough and Black seem easy. Louis's career made a meteoric rise. Though Roxborough and Black continued on as Louis' managers, a white man, Mike Jacobs, now called the shots for the fighter.

Managers' Concerns

Before the first Schmeling fight in 1936, Louis got complacent. Rather than concentrate on his training, he took up golf. "Two times Roxy chased me off the golf course -- I was dehydrating myself under that hot sun," Louis recalled. The concerns of Louis' managers and trainer turned out to have merit; Schmeling handed Louis his first professional defeat.

At Contract's End

In 1944, Roxborough was charged with running the numbers racket in a sweep that also indicted an ex-mayor. He served two and half years in jail. While one manager was in jail, Louis went to the other to borrow some money, but Black claimed he didn't have the funds. They were at the end of their decade-long contract and Louis chose to part ways with Black, signing up his wife, Marva Trotter, as manager, and also enlisting Marshall Miles, a black man from Buffalo. John Roxborough remained his co-manager. Roxborough died in 1975; Julian Black died less than six months later. Louis felt he owed Roxborough his career and regretted never making amends with Black.