Max Schmeling (1905-2005)

I had nothing personally against Max, but in my mind, I wasn't champion until I beat him. The rest of it -- black against white -- was somebody's talk. I had nothing against the man, except I had to beat him for myself."— Joe Louis

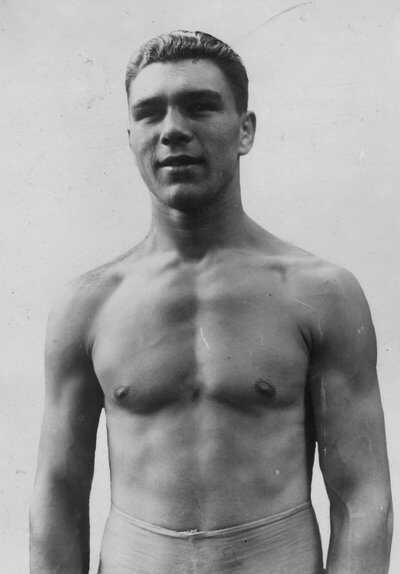

Max Schmeling was born on September 28, 1905, in rural northeastern Germany, the son of a ship's navigator. Boxing was virtually unknown in Germany at the time, but Schmeling's father had seen the sport in his travels. In his early teenage years, Max saw a film of a heavyweight championship fight between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier. He was hooked. Leaving home to find like-minded enthusiasts, Schmeling went to western Germany and began fighting in amateur tournaments. The young man drew the attention of Arthur Bülow, editor of Boxsportmagazine.

European Champion

Schmeling turned professional in 1924 and maintained a good win-loss record thanks to his powerful right hand. Frustrated with managers who did not prioritize his career, Schmeling moved to Berlin, hoping Bülow would be able to help him. Bülow agreed to finance his training and Schmeling came under the wing of Max Machon, who would be his trainer until the end of his career. In 1927, he won the European championship, the first German to do so.

Seeing the World

His mentors took him on his first trip outside of Germany. Schmeling watched a world championship bout in London. The high society in the audience made an impression on the young man, and so did the fierce concentration of the American Mickey Walker as he pummeled his challenger.

Sizing Up Strangers

As European champion, Schmeling found himself invited into Berlin's elite society. During the era known as the Weimar Republic, boxing had become a popular spectator activity and Schmeling himself was a celebrity. He bought a tuxedo and tails and began reading more. "I said to myself, 'You're a man from a humble background, what you didn't learn in school, you'll learn now. Catch up.'" He joined a circle that included race car drivers, playwrights, filmmakers, actors and dancers. The artist George Grosz asked to paint his portrait, and the two men had thoughtful conversations during the sittings. "It occurs to me that boxers and painters have to... be able to size up the stranger facing them right away.... I have to come up with a picture, you have to come up with a fight strategy," said Grosz. Schmeling agreed, "I tried to study [my opponents] closely, which gave me the reputation of being a slow starter... You have to study his movement and reactions, and everything depends on finding out his style and habits in the first few rounds."

A Name in America

For his next challenge, Schmeling had to go to America. Bülow was not prepared for the American fight-promoting scene, however, and Schmeling replaced him with Joe Jacobs, a Jewish manager who could get Schmeling in the ring. Jacobs quickly made a name for the "Black Uhlan of the Rhine" and when Gene Tunney retired as undefeated champion, Schmeling was invited to join an elimination tournament to find a new champion. After defeating Paolino Uzcudun, Schmeling faced Jack Sharkey for the title.

Meaningless Title

On June 12, 1930 at Yankee Stadium, Sharkey came out strong. Schmeling figured that if he survived three rounds, Sharkey would tire himself out, and so he boxed defensively and paced himself. In the fourth round, Schmeling began to fight more aggressively when he was hit by a punch and went down, "as if I were paralyzed." He had been hit below the waist. Sharkey was disqualified for the low blow and Schmeling became the new heavyweight champion of the world, the only time the title was decided by a foul. "I can't accept the title!" Schmeling said to his trainer. "To win it this way doesn't mean anything to me."

Champion and Celebrity

After defending his title against Young Stribling in 1931, Schmeling was recognized as champion by all his critics. He was the first European to hold the world heavyweight title. In 1932, he married a beautiful blond movie star, Anny Ondra, and the two became Germany's most glamorous couple, even starring together in a movie.

Unfair Defeat

For the rematch with Sharkey, the referee was one of Sharkey's closest friends. The fight started slowly, and Schmeling dominated the last five rounds. Unbelievably, the referee named Sharkey the new champion on points. Former heavyweight champ Gene Tunney, New York mayor Jimmy Walker and the American newspapers were unanimous in their condemnation of the decision, but there was nothing to be done.

Life Under Nazism

Back in Germany, Adolf Hitler's Nationalist Socialist Party was starting to make life very uncomfortable for the artists in Schmeling's social circle. Filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch and actress Marlene Dietrich went to Hollywood, Writer Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill emigrated to New York. But Schmeling's victories became a point of pride for Hitler's Germany, and Schmeling received favored treatment from the authorities.

P.R. for Hitler

Under the circumstances, Schmeling entered into a devil's bargain. As a representative of Germany overseas, the boxer would be useful to the Nazis as a mouthpiece. According to scholar David Bathrick, Hitler summoned Schmeling to a meeting in June 1933, and told him: "When you go to the United States, you're going to obviously be interviewed by people who are thinking that very bad things are going on in Germany at this moment. And I hope you'll be able to tell them that the situation isn't as bleak as they think it is." Sportswriter Volker Kluge continues the story: "After arriving in the States, Schmeling held a press conference. Many journalists were waiting to hear about conditions in Germany. Schmeling told them that everything was okay and quiet in his home country. He denied that Jewish people were persecuted. His assignment was to calm down the American people."

Strategy Against Louis

In anticipation of his first fight against young phenom Joe Louis, Schmeling had watched Louis beat Uzcudun. Asked for a comment afterward, the German said only, "I saw something." He studied films of Louis and confirmed that for a split second after his left jabs, Louis let his arm drop -- just long enough, Schmeling thought, for him to deliver one of his devastating right-hand punches.

The 1936 Fight

Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels had ordered Nazi newspapers to bury the story of the fight. German sportswriter Gerd Reimann says, "Hitler was annoyed that [Schmeling] was going to fight a Negro." Yet Schmeling, the 10-1 underdog, won the fight much as he had planned. The Nazis saw his victory as a victory for themselves, and their racist views. "Stayed up all night," Goebbels would report. "At 3 a.m. the fight begins. In round 12 Schmeling knocks out the Negro. Wonderful... The white man defeats the black man, and the white man was a German!"

Hitler's Hero

Schmeling flew back to Germany on a brand-new, futuristic conveyance, the airship Hindenburg. His victory had further endeared him to Hitler, who decided to release a film of the fight as a feature throughout Germany.

Aching for the Title

Schmeling had figured that by defeating Louis he had earned a right to fight Jimmy Braddock for the title, but machinations behind the scenes and anti-Nazi protests in New York made the matchup unpalatable to the American audience. Louis took on Braddock and won the title instead. Louis, however, was eager for a rematch with Schmeling and a second fight was arranged for June 1938. Louis won the bout decisively in the first round.

Compassionate and Modest

Later that year, on Kristallnacht, Schmeling took an enormous risk and hid the two teenage sons of a Jewish friend in his Berlin hotel room. The boxer claimed to be sick and did not allow any visitors. When the opportunity presented itself, Schmeling smuggled the two boys out of the country. Henri Lewin, who became a Las Vegas hotelier, credits Schmeling with his life; characteristically, the modest Schmeling made no mention of this episode in his own autobiography.

Wartime and Afterward

Schmeling fought a few more times, but without much success. When Germany went to war, he was drafted into the German Army, but unlike Joe Louis, Schmeling saw front-line combat as a paratrooper. At the end of the conflict, British authorities would clear him of any complicity in Nazi crimes. In the privation of post-war Germany, Schmeling and his wife did their best to scrape by, turning to farming, a failed return to the ring as a boxer, and then a brief career as a boxing referee. A former New York boxing commissioner who became a Coca Cola executive remembered Schmeling as a non-Nazi hero to the German people, and offered him the Coke franchise in Germany. Schmeling finally prospered, as a businessman.

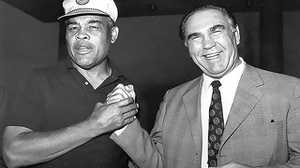

Reunions with Louis

Invited to referee a bout in Milwaukee in 1954, Schmeling first flew to New York to visit Joe Jacobs' grave. On the same trip, he drove to Chicago and found Joe Louis at home. They reminisced and renewed an acquaintance that lasted until Louis' death. The two even appeared on a popular television program, "This is Your Life," which reunited Louis with a host of people from his past. When Louis died in 1981, Schmeling helped pay for the funeral. In his later years, Max Schmeling continued to live outside his hometown of Hamburg, Germany, until his death in February 2005 at the age of 99. "I had a happy marriage and a nice wife," he would tell an interviewer before his death. "I accomplished everything you can. What more can you want?"