The Mississippi River Commission and the Army Corps of Engineers

Mississippi River Commission’s “Levees only” policy failed to tame the Mississippi River and prevent flooding.

Ten thousand River Commissions, with the mines of the world at their back, can not tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or confine it, can not say to it, Go here or Go there, and make it obey. — Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi

Native Americans told the first European explorers to expect the Mississippi River to flood every 14 years. Since then, every generation of settlers to the region has attempted to control the river by building levees, or protective, raised embankments, alongside it. Prior to 1882, Mississippi Delta planters had to rely on their own efforts to build and maintain levees. But local efforts were not always effective. They needed a more advanced levee system, and for that they turned to the federal government.

In 1879 Congress created the Mississippi River Commission to oversee federal funds for flood control. The Commission was a response to the long-standing dispute between James Buchanan Eads, an influential civilian engineer on the Mississippi River, and Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, Chief the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, over how best to control the river. At the same time, Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to participate in levee building on the Mississippi if matters of navigation were involved. Although the Commission was supposed to combine the ideas of both civilian and military engineers, in practice it was controlled entirely by the Corps.

Up until the 1830s, the only place to receive training in engineering was at West Point, and only the very best cadets were tapped to join the Army Corps of Engineers. In the succeeding decades a cadre of highly trained civilian engineers emerged as well. The Army and civil engineers clashed repeatedly, especially over Mississippi River flood control policy. Although there was extensive scientific debate over flood control policy for the river, and many prominent engineers warned of the dangers of excessive reliance on levees, over time the Mississippi River Commission solidified its commitment to levees.

In 1885 the Mississippi River Commission adopted a "levees only" policy. This policy was based on the theory that by containing the river with levees, the force of the high water would scour out the floor of the river, deepening the channel sufficiently to carry any flood water straight out to the sea. The use of manmade reservoirs, outlets and cutoffs for runoff were rejected time and time again. For the next 40 years, the River Commission stuck to this policy, not only refusing to build any manmade outlets for flood waters, but also actively sealing up the river from many of its natural outlets.

The Army engineers working on the levees were soldiers, not scientists, and the "levees-only policy" remained uncontested within the Corps of Engineers. In reality, the levees caused the river to rise, requiring higher and higher levees to contain the waters. It was a vicious cycle: levees built in 1850 to a height of seven feet had to be raised to as much as 38 feet -- the height of a four-story building. With each passing year, as the levees grew taller and stronger, so did the force and volume of the river, and the consequences of a levee break grew ever more dangerous. When levees broke, the Mississippi River Commission and the Army Corps of Engineers blamed flooding on substandard building techniques. They never questioned the "levees only" policy.

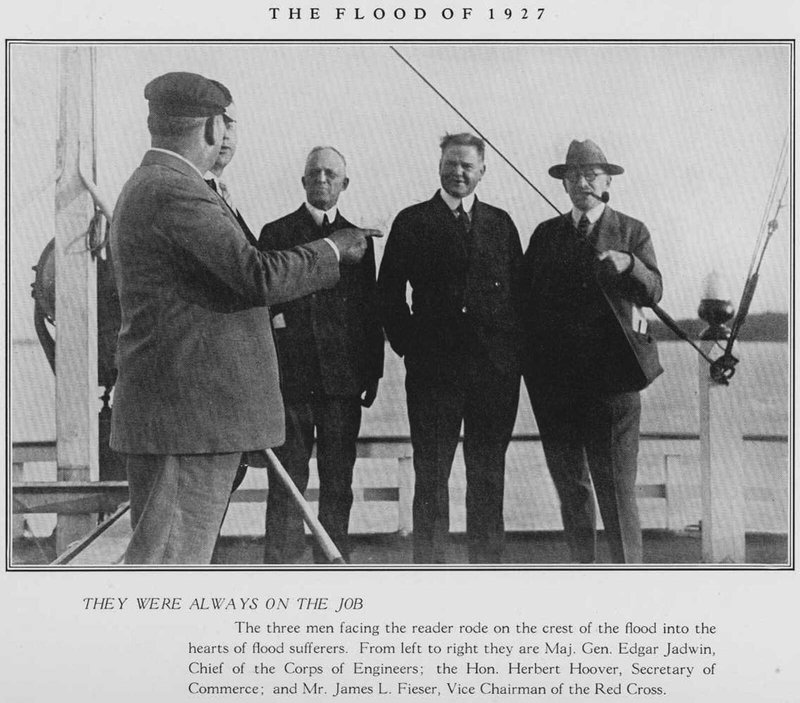

The Mississippi River Commission remained confident in their policy, and in 1926, the Army Corps of Engineers asserted that the levees were strong enough to contain the river and prevent any future flooding. One year later, the Great Flood of 1927 would prove just how wrong they were.