Damming the American West

Do ideas from the past offer new ways of thinking about the environment?

Earlier this month the nation’s second largest reservoir hit a landmark low water level. If Lake Powell loses just 30 more feet of water, Glen Canyon Dam will no longer be able to generate electricity for the five million residents of six western states and the Tribal Nations who rely on the dam for water and power. The water crisis in the arid Southwest may soon spark an energy crisis.

When Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1966, it was the culmination of a decades-long effort to use large dams to control the flow of the West’s riverways. Like its predecessors, Hoover Dam (1936) and Grand Coulee Dam(1942), it was considered an engineering marvel. Today, it has come to stand as a symbol of mid-20th-century attitudes about harnessing nature to human needs. Now, however, as a “megadrought” punishes the region, policy makers and engineers are debating whether or not Lake Powell can survive and if its dam should be decommissioned.

To better understand the current water crisis in the arid West we need to go back in time to chart the evolution of ideas about water as a resource. Revisiting the history of water technology in the region also helps us better understand how European settlers viewed nature differently than the region’s original inhabitants.

Indigenous people in the West worked hard to manage their water resources long before the arrival of European or Anglo settlers. Across the land base that became the states of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and California, Indigenous people constructed sophisticated irrigation ditches, canals, earth barrier dams, and storage systems to sustain them during dry periods. The ancestors of residents of the Laguna Pueblo in present day New Mexico, for instance, built reservoirs by constructing earthen dams as early as 1370.

In what is today Los Angeles, the Tongva created a thriving settlement—dating back 1000 years—next to what is now called the Los Angeles River, carefully calculated on how many people the water supply could support. When the Spanish arrived in 1769, they found a community of over 200 people living just west of the river. The Spanish established a settlement on the river nearby. But while the river made both settlements possible, they, like the Anglo-American settlers who would follow, believed they could bend nature to their will.

In the 1850s and 1860s, when white settlers arrived in the area near where Glen Canyon Dam now sits, near the Utah-Arizona border, they immediately sought information about water from Indigenous people. Paiutes taught them, for instance, how to locate water by finding willow trees away from riverbeds. Willows, Salix lasiolepis, are native to the West and grow best in rmoist soils. The surveyors and explorers sent by the federal government to map the Colorado River and the surrounding plateau also sought Indigenous knowledge and hired Indigenous guides to help them navigate the region, find food supplies and learn more about the land’s potential resources. Indigenous guides proved essential to the success of these missions – which also sped up the processes of Indigenous dispossession. The white surveyors and settlements also marked a change in how people on the plateau would think about nature. As Zuni elder Jim Enote explained, whereas Indigenous people looked at land and water as part of a larger cosmological whole, European and American settlers viewed land and water primarily as commodities that could be leveraged to build communities and wealth. There were, however, different ideas about how those communities should take shape.

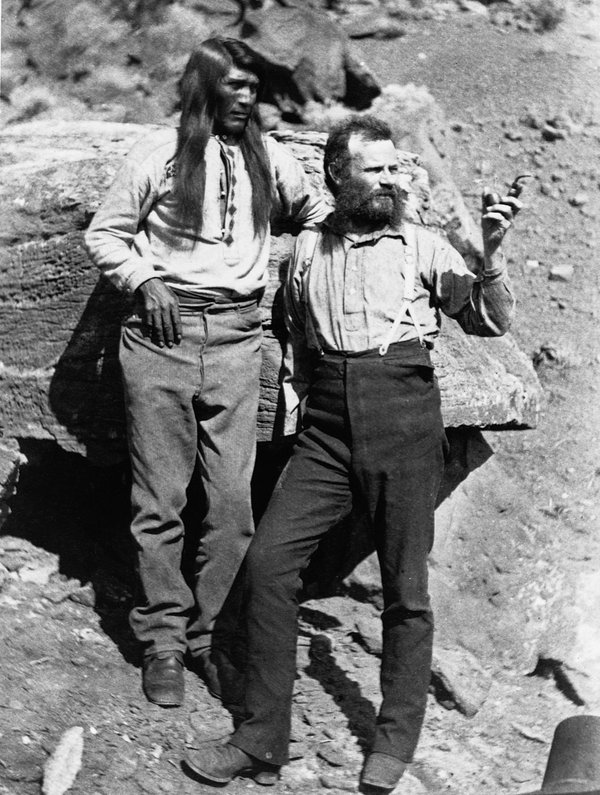

In late May 1869, a 35-year-old veteran of the Civil War, John Wesley Powell, headed an expedition to map nearly 1,000 miles of the Colorado River and its tributaries through present-day Colorado, Utah, Arizona and Nevada. With the help of Paiute guides, Powell produced detailed descriptions and valuable maps as his team navigated the entirety of the Grand Canyon. Two years later, Powell retraced much of his original journey and published his results in a popular account.

Unlike most American settlers, Powell believed, in essence, that the region should be defined by water and its natural movement and that people could move to be near water; not that water should be moved to supply people in far off cities and settlements. But he also advocated the removal of Indigenous people through the creation of reserves.

Powell argued that decisions about politics, economic development and settlement patterns should first account for water. Instead of the traditional 160-acre homestead plan that checkerboarded much of the Great Plains, Powell argued for the formation of small irrigation districts and pasturage farms. To support this controversial position, Powell studied the region’s rainfall patterns and immersed himself in the growing standards and seasons for agricultural production. He suggested that the residents of the region form a large cooperative body and be given collective control of water resources. His plan was never implemented in large part because he was proposing an entirely new national political system based on water availability.

Yet, the boundaries of western states and territories had already been drawn, and because Powell’s journeys coincided with a period of frenzied land development in the American West—and most of his contemporaries were buzzing about the commercial promise of the arid West—the country went a different way, perhaps missing an opportunity to live in better balance with nature. While Powell’s proposal for “hydrographic basins” was never adopted, it illustrates that there were potential alternatives to support populations across the arid West than the one the United States ultimately chose.

Instead, the states and federal government decided to use technology to move water around the region to “make the desert bloom.” By 1902, the Federal Government created the Bureau of Reclamation to support the construction of irrigation technology and other water works. State and city governments also went “all in” on large water projects, embracing the idea that it would be easier to bring water to where people had been convinced to live – due in good part to regional boosterism – than to change settlement patterns.

Los Angeles provides a key example of this mentality. Boosters and city planners decided that water technology was the answer to the natural limits of growth. In 1905, the voters in Los Angeles approved a $23 million bond initiative to support construction of an aqueduct from the Owens Valley, over 200 miles away near the edge of the Great Basin, where American settlers had displaced Paiutes a generation earlier. Under the direction of William Mulholland, head of the city’s Department of Water and Power, the monumental engineering project was built between 1908 and 1913, bringing four times as much water to Los Angeles as the Los Angeles River could offer. But it wasn’t enough. City planners and engineers still worried about the city’s future water supply. As a result, the city of Los Angeles moved to build one of the largest dams in the United States, a dam whose eventual failure marks one of the worst engineering disasters in American history.

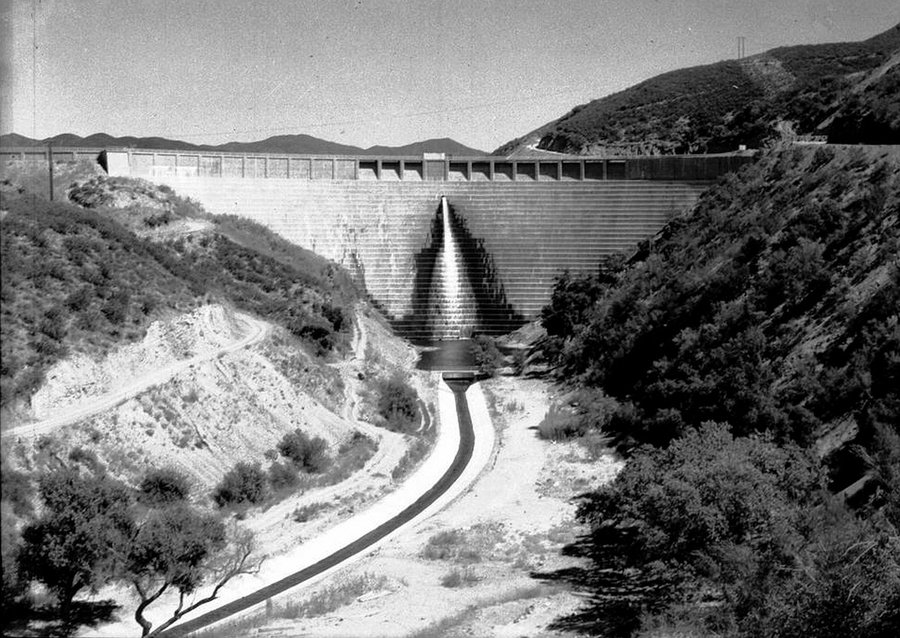

The St. Francis Dam, which stood 200 feet tall and 700 feet wide when completed in 1926, was designed to store about two years’ worth of water for the expanding city—about 12 billion gallons of water. When it collapsed in 1928, more than 400 people died and neither Mulholland nor his reputation ever recovered. The tragedy did not, however, dampen the impulse for massive dam building in the American West. Instead, it seems to have deepened the resolve of politicians, planners, engineers and citizens that massive hydro-power dams would solve water supply problems as well as providing a brighter, electrified future.

In part, that was because politicians, boosters, agriculturalists and the government had already decided to apportion the water of the Colorado River through the Colorado River Compact of 1922. The larger plan was to divide the water of the river between the upper-basin and lower-basin states to build dams on the river and its tributaries to enable regional growth, again, moving the water to where people had settled, rather than encouraging people to settle in larger watershed states as Powell had envisioned.

The first dam to be proposed on the Colorado River was Boulder (now called Hoover) Dam. The story of Hoover Dam is one of engineering prowess. Built by the Bureau of Reclamation, the Hoover Dam was the tallest of its kind in the United States. Hubris similar to the kind that inspired St. Francis Dam was also on display at Hoover Dam. Engineers claimed that they “tamed” the wild and unpredictable Colorado River. In so doing, they facilitated the growth of the region’s (primarily white) communities as well as the industries that served regional and national interests. In his speech dedicating the dam, Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared the project had done more than create electricity for industry, jobs for people and reserve water for human use, it provided the nation with a hopeful future at a moment when things seemed especially bleak. Controlling nature with technology was a driving impulse of the era.

By the 1940s and 1950s, the Bureau of Reclamation continued to push forward bigger and bigger engineering schemes, with popular support. Architects of the Colorado River Storage Act (1956) proposed to build five additional storage dams on the Colorado River and its tributaries, all but one of which (at Echo Park), were eventually built.

In building massive dams, we used technology to dominate nature and supply the region’s cities with water and power. The cheap electricity that Hoover and Glen Canyon produced, for instance, helped fuel a building boom that made air-conditioning routine, which in turn eliminated the incentive to build passive, non-carbon producing building styles. Ironically, the storage of massive amounts of water may have even given consumers a false sense of security which, in turn, led many to overuse water in previous years. Eventually, however, most people have realized that the comforts brought by cheap electricity have also spawned decades of overconsumption of both resources and contributed to harmful climate changes, making engineers and residents of the region question both the need for the dam while simultaneously worrying about future water needs. In December of 2021, Dan Beard, for instance, who served as Commissioner for the Bureau of Reclamation from 1996-2002, and is now the Chief Administration Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives, said that “Lake Powell and Glen Canyon Dam should be scrapped and completely decommissioned.” Critics like Beard contend we do not need both Hoover and Glen Canyon Dam. One idea is that Hoover Dam could do more to serve the region. Increased investments in solar power could also help. There are definitely trade-offs that consumers will need to make if Glen Canyon Dam is either decommissioned or stopped producing electricity due to falling water levels.

Water infrastructure projects, and the ideas that helped place them on the landscape, offer lessons in unintended consequences and missed opportunities. We neglected the expansive relationship with the natural world cultivated by Indigenous people and ignored Powell’s suggestions. But might this history also offer us solutions to the current climate crisis and drought? Many scholars and policy experts now call for a new look at some older ideas. Scholars Karletta Chief, Alison Meadows, and Kyle Whyte propose engaging Southwestern Tribes in management issues as a way to move forward, noting their “respect for their ancestors and ‘Mother Earth’ speaks of unique value and knowledge systems different than the value and knowledge systems of the dominant United States settler society.” Geographer Andrew Curley (Diné), suggests that contemporary Indigenous communities can help us find new ways to think about the environment: “We need to reinvest in Indigenous approaches to science and technology, ones designed to sustain and not conquer our species in the world among our ourselves and nonhuman persons.” This seems like a prudent and necessary step as Lake Powell continues to evaporate. Perhaps by looking back, we can better chart a way forward.

Erika M. Bsumek is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Indian-made: Navajo Culture in the Marketplace, 1848-1960 (University Press of Kansas, 2008), the coeditor of a collection of essays on global environmental history titled Nation States and the Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental History (Oxford University Press, 2013) and the forthcoming, The Foundations of Glen Canyon Dam: Infrastructures of Dispossession on the Colorado Plateau (University of Texas Press, 2023).

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.