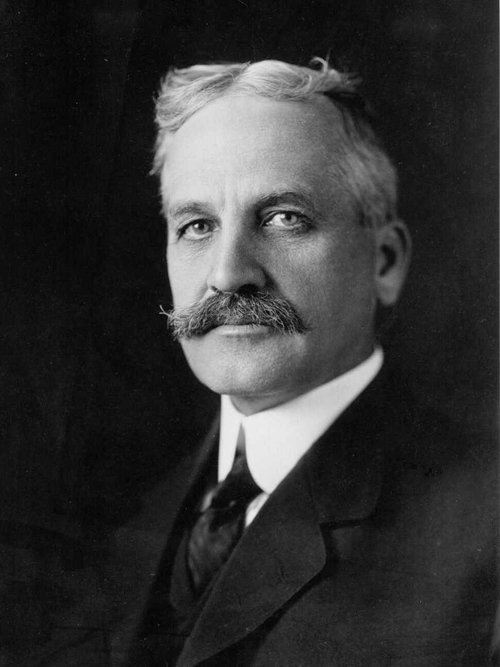

LeRoy Percy

LeRoy Percy ran both his law practice and plantations with a vengeance, and by the early 1900s he controlled plantations exceeding 20,000 acres.

LeRoy Percy may have been born into Mississippi Delta aristocracy, but by the time he took the reins of the family business at age 28, Percy had already made a name for himself in his own right. After receiving his bachelor's degree from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, LeRoy Percy followed in his father and grandfather's footsteps at the University of Virginia Law School. Unlike his forebears, however, he sped through three years of courses in just one year and returned swiftly home to Greenville, Mississippi, to establish himself. Percy ran both his law practice and plantations with a vengeance, and by the early 1900s he controlled plantations exceeding 20,000 acres. His power and prestige in the area was unparalleled.

LeRoy Percy's influence didn't stop at the Mississippi border. A hunting partner of President Theodore Roosevelt and a poker mate of the United States Speaker of the House, Percy had friends on the Supreme Court, in the United States Senate and in the executive office. With his position as governor of a Federal Reserve Bank and as a trustee of both the Carnegie and Rockefeller Foundations, Percy was on close terms with the major industrialists of his day. A skilled lawyer and back-room politician, he relentlessly pursued his interests in the corridors of Washington and in the boardrooms of Chicago, New York and London.

In the Mississippi Delta, nothing was more vital to the success of Percy's empire than labor. Although he tried repeatedly to lure Northern farmers and immigrants to Washington County, no one but African Americans came in large numbers or stayed long in the area. Guided by a combination of noblesse oblige and calculated self-interest, Percy was determined to convince his workforce that they had a future in the Delta. As a result, conditions for his tenants were among the most favorable in Mississippi. At a time when African Americans in the South were disenfranchised, lynched and chased off their land, Percy saw to it that they received loans for mortgages to buy farms in the Delta. Washington County had African American policemen, judges and mailmen, and the best schools for African Americans in the state. Percy's patrician liberalism paid off. Greenville prospered, and Washington County was an island of comparative civility in the Jim crow South. In 1910, Percy was appointed to fill a vacant seat in the United States Senate, achieving the highest public office ever held by a member of the Percy family.

Percy's victory was, however, short-lived. His agenda clashed with the populist forces outside the Delta. His greatest rival was the governor of Mississippi, James K. Vardaman, who tapped into populist racial politics and publicly supported white supremacy. When Percy came up for re-election in the Senate, Vardaman's allies came out in full force and crushed Percy in the election. Vardaman won the Senate seat, and his supporters, including the Ku Klux Klan, gained a foothold in the Delta.

Although he had been defeated by racists in his Senate race, Percy would not allow the Klan to take over Washington County. It was vital that he succeed; his wife was Catholic, his partner a Jew and his empire depended on African American labor. In 1922, Percy publicly opposed the Klan, and despite threats on his life, refused to back down. His lone defiance of the Klan caused a national sensation, made Percy a hero, and kept the Klan out of Greenville.

Yet the delicate balance LeRoy Percy had maintained between the black and white communities in Washington County was soon washed away by the Great Flood of 1927. Percy, whose son Will Percy headed the relief effort in Greenville, turned a blind eye to the brutal treatment of the African American laborers and their families during the crisis. When the floodwaters receded, the bond between the Percy family and their tenants would never be the same again. With their homes destroyed and their crops ruined, there was no reason for the sharecroppers to remain in Washington County. As if to fulfill LeRoy Percy's worst nightmare, thousands of African Americans cleared out of the area, most of them for the North. Within a year, 50 percent of the Delta's black population had already departed. Heartbroken by the demise of his empire and the subsequent death of his wife, Senator Percy died in Greenville, Mississippi, of a heart attack on December 24, 1929.