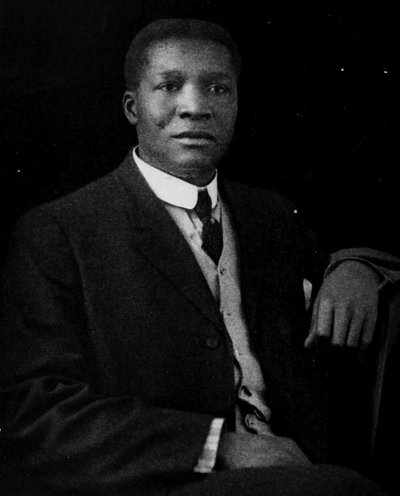

Robert Moton and the Colored Advisory Commission

Herbert Hoover appointed Robert Moton to investigate allegations of abuse in the flood area.

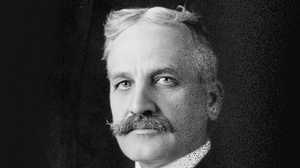

In 1922, former President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court William Howard Taft elected Robert Russa Moton to give the chief address at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial. At the time, many considered Moton to be the most powerful African American in the country. In elite, white political and financial circles, his status was unparalleled.

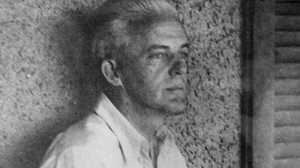

In race relations, Robert Moton advocated accommodation, not confrontation. He firmly believed that the best way to advance the cause of African Americans was to convince white people of black people's worth through their exemplary behavior. Never one to rock the boat, he didn't fight segregation or challenge white authority.

A protégé of Booker T. Washington, Moton had succeeded him as principal of Tuskegee Institute. From this position, Moton worked long and hard to win the trust of white politicians and philanthropists and secure donations for Tuskegee and other African American institutions and organizations.

His power in the country stemmed from the money he could raise from whites who appreciated his conservative views and methods. In addition to his access to leaders in Washington, Moton sat on the boards of major philanthropic organizations with the likes of Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller Jr., and his influence was considerable. When Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, provided the funding to build more than 6,000 "Rosenwald" schools for rural Southern African Americans, Moton's skills were clearly in play behind the scenes.

Over the years, Moton's words and deeds impressed Herbert Hoover, who invited Moton to visit him anytime he was in Washington. However, during the Great Flood of 1927, it was Hoover who found himself calling on Moton for assistance. Secretary of Commerce during the Coolidge administration, Hoover had his eye on the presidency. When President Coolidge placed Hoover in command of all flood relief operations during the disaster, it seemed to be the perfect vehicle to raise his national profile and revive his reputation as the "Great Humanitarian."

Drawing on lessons he had learned feeding the starving European refugees of World War I, Hoover swept into action. He cut through bureaucratic red tape, got aid to victims devastated by the flood and was dubbed a hero by the national press. There was only one thing that could tarnish Hoover's glowing image — the treatment of African Americans in the Washington County levee camps. Hoover had visited the area and had approved the local flood relief committee's decision, under the leadership of Will Percy, to keep the African American refugees on the levee. But as conditions deteriorated in the camps, word slowly filtered North, and the scandal threatened to derail Hoover's presidential ambitions.

Hoover's friends urged him to get what they called "the big Negroes" in the Republican Party to quiet his critics, and Hoover turned to Robert Moton for the job. Hoover formed the Colored Advisory Commission, led by Moton and staffed by prominent African Americans, to investigate the allegations of abuses in the flood area.

The commission conducted a thorough investigation and reported back to Moton on the deplorable conditions. Moton presented the findings to Hoover, and advocated immediate improvements to aid the flood's neediest victims. But the information was never made public. Hoover had asked Moton to keep a tight lid on his investigation. In return, Hoover implied that if he were successful in his bid for the presidency, Moton and his people would play a role in his administration unprecedented in the nation's history. Hoover also hinted that as president he intended to divide the land of bankrupt planters into small African American-owned farms.

Motivated by Hoover's promises, Moton saw to it that the Colored Advisory Commission never revealed the full extent of the abuses in the Delta, and Moton championed Hoover's candidacy to the African American population. However, once elected President in 1928, Hoover ignored Robert Moton and the promises he had made to his black constituency. In the following election of 1932, Moton withdrew his support for Hoover and switched to the Democratic Party. In an historic shift, African Americans began to abandon the Republicans, the party of Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, and turned to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Democratic Party instead.