The John Lewis I knew

Historian and biographer of the Freedom Riders remembers the civil rights icon

As a civil rights historian who has studied Lewis’ long career, I know how much he has meant to the ongoing fight for civil and human rights in the United States. For more than half a century, despite numerous beatings and arrests, he has been a rock of strength, a singular moral force prodding Americans of all colors, classes and faiths to live up to the professed national ideal of liberty and justice for all.

I know this, in part, because I have had the rare privilege of observing him up close and in person, on several occasions listening to his strong and penetrating voice as he explained why and how he committed his life to the nonviolent freedom struggle once led by his idol, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I regard these conversations as a gift from a great man who, without a hint of pretense or self-importance, offered me a life-affirming glimpse of his plan to “redeem the soul of America.”

Our initial meeting took place at his Washington office in the fall of 2000. Two years earlier I had begun researching a book on the Freedom Rides of 1961, and much of my early work involved locating and arranging interviews with as many of the 436 Freedom Riders as I could find. Congressman Lewis, the most famous of the original 13 Freedom Riders, was my first interviewee. Sensing my nervousness — I had never been in a congressman’s office before, much less the office of a civil rights icon — he immediately put me at ease. “Just call me John,” he said. “Everyone does.” We both smiled, launching a friendship that would last until his death 20 years later.

Listening to him as he recounted his experiences as a Freedom Rider, and gazing at all the historic photographs and other mementos of the movement that covered the walls of his office, I was transported back to a time of glorious and courageous struggle — ”good trouble,” as he called it. Speaking softly but with emotion, he described the power of nonviolence and his lifelong search for the “beloved community.”

After an hour or so of truth-telling, he sent me on my way, but not before asking me to help him find the “lost” Freedom Riders whom he feared would miss the upcoming 40th reunion scheduled for the following spring. In return, he offered me a special invitation to the reunion, assuring me there would be potential interviews galore during the three-day event.

The reunion featured a festive re-creation of part of the original Freedom Ride that left Washington on May 4, 1961, bound for New Orleans and two weeks of testing compliance with two Supreme Court decisions that outlawed racial segregation in interstate bus travel. After a day of rousing reminiscence-filled speeches in Washington, plus a reprise of the famous Chinese dinner the original 13 Riders had eaten on the evening before their departure (known as the “Last Supper” in Freedom Rider lore), the gathering flew to Atlanta to begin a multi-city bus tour that would wind its way to Anniston, Birmingham and Montgomery — the three Alabama communities where the Riders had encountered violent white supremacist resistance 40 years earlier.

The return to these historic cities, where bombings and beatings had tested their courage and commitment, was emotionally wrenching for many of the Riders, especially for those who had not been back to Alabama for decades. But with Lewis leading the way, the Riders somehow managed to balance pride and pathos, sustaining a joyous mood of celebration while neutralizing the fearful ghosts of Jim Crow violence.

As I watched the drama of reengagement with the ideals of their youth, Lewis’s humane and inspiring influence was seemingly everywhere, in his unreserved embrace of his fellow Riders, in his stirring references to “the beloved community,” and in his clarion call for continued struggle against discrimination and inequality. His unblinking assessment of how far the freedom struggle had come and how far it still had to go had the ring of truth, reinforcing his uncommon authority as a leader.

While all of this was going on, he could easily have forgotten the historian on the bus. But he didn’t. Treating me like an honored guest, he introduced me to dozens of Riders, always encouraging them to talk with me at length about their experiences. The resultant interviews and friendships provided an indispensable foundation for the research that would dominate my life for the next five years.

There would be many more interviews — more than 200 in all — some conducted at other Freedom Rider gatherings in Mississippi, Louisiana and California. But it all began with Lewis’ gracious nurturing in 2001. He had published his own memoir, Walking with the Wind, in 1998, but he sensed that a broader and deeper history of the Freedom Rides, especially one informed by extensive oral testimony, would help sustain the legacy of what had happened in 1961. He wanted the empowering story of the Rides to become part of historical education for a broad swath of Americans, especially for younger Americans born too late to experience the civil rights upheavals of the 1960s.

After the book Freedom Riders finally appeared in print in 2006, no one took more delight in its popular reception and widening influence than Lewis. At several public appearances, he thanked me for validating the pivotal importance of the Freedom Rides as a template for the citizen politics of the ‘60s and ’70s. But, of course, the preponderance of the debt went the other way. Without his help and inspiration, the book project might have foundered in the early stages.

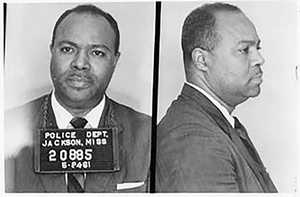

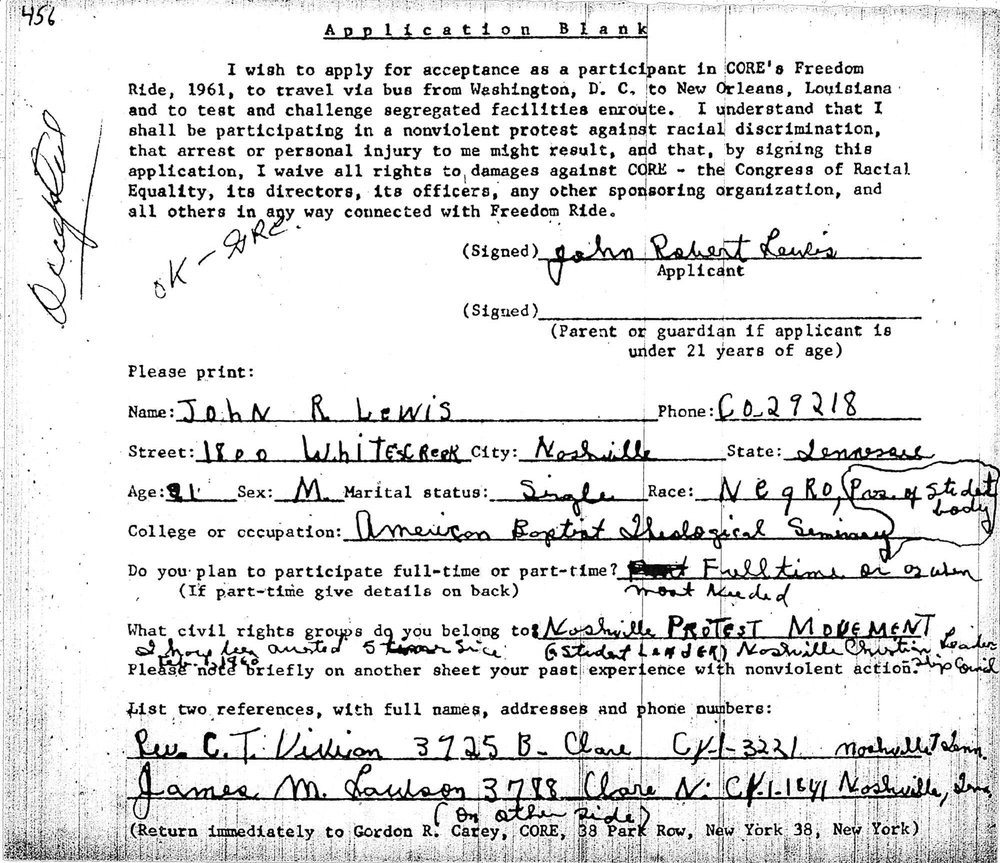

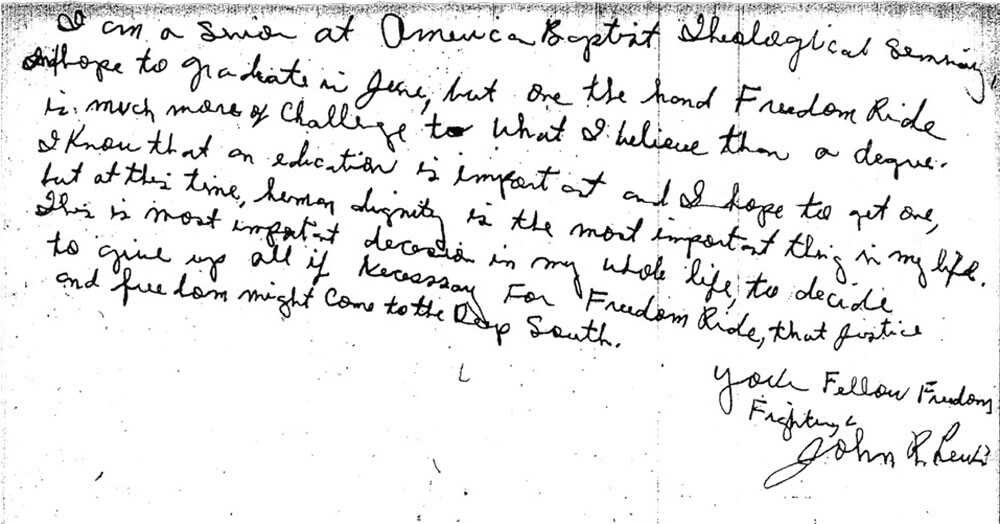

Later, when the book became the basis for an Emmy winning American Experience documentary directed by Stanley Nelson, Lewis appeared in and promoted the film, which ultimately spread the Freedom Rider saga to millions of viewers around the world. In one of the film’s opening frames, he reads from his original application to become a Freedom Rider, stating his willingness to drop out of college to join the Ride: “I know that education is important. But at this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life, that justice and freedom might come to the Deep South.”

The national broadcast of the documentary on PBS in May 2011 coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides. This time the reunion would be in Chicago, where Lewis and 180 other Freedom Riders gathered for an appearance on Oprah Winfrey’s popular television show. With the Riders filling the studio, Oprah interviewed several individuals, including Lewis and a former Klansman, Elwyn Wilson. At age 19, Wilson had attacked Lewis outside a bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The local police interrupted the assault, preventing serious injury, but the young Freedom Rider from Nashville refused to press charges, puzzling Wilson and his Klan cohorts.

Wilson soon left the Klan and later felt guilty about what he had done. But he did not act upon his contrition until January 2009, when he noticed Lewis sitting behind President Barack Obama on the inaugural stage. A tearful phone call and apology to Lewis followed, and to Wilson’s surprise the congressman invited him to Washington for a private conference.

Meeting in Lewis’s office, the two men prayed together and talked about life, hope and redemption. Emerging as friends, they kept in touch until Oprah’s search for a dramatic reconciliation story brought the two men together in front of a national audience.

Nervous and unaccustomed to speaking in public, a noticeably frail and tearful Wilson appeared to be on the verge of breaking down until Lewis reached out and took his hand, announcing to the audience: “He’s my brother.” I was sitting just a few feet away, and this supreme act of kindness took my breath away. This is the John Lewis that I will always remember.

This article is adapted from an essay originally published in the Tampa Bay Times

.

Raymond Arsenault, the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida, is currently writing a biography of John Lewis that will be published in Yale University Press’s forthcoming Black Lives series.

A new AMERICAN EXPERIENCE collection, currently featuring a selection of our award-winning films from Stanley Nelson (Firelight), documenting pivotal moments in the 20th century civil rights movement— along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with race, democracy and justice.