Freedom to Travel

The victory won by the Freedom Riders was decisive and unambiguous, expanding the freedom of African-Americans to travel through the United States.

Since the institution of Jim Crow laws at the close of the 19th century, African-Americans in the South had been forced to endure substandard, segregated conditions while traveling on railways and buses. Blacks were forced to sit in the back of the bus and forced to use separate waiting rooms, drinking fountains, and rest rooms. In addition to the humiliation of segregated facilities, the threat of violence was always present for black travelers.

"You didn't know what you were going to encounter," said Freedom Rider Charles Person. "You had night riders, you had hoodlums. You could be antagonized at any point in your journey. Most of the time it was very, very difficult to plan a trip."

On July 16, 1944, Irene Morgan was arrested by the sheriff of Middlesex County, Virginia, after refusing to give up her seat on a Greyhound bus while traveling home from Baltimore, MD. The legal staff of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took up her case, and on June 3, 1946, the U.S Supreme Court ruled in her favor, striking down racial segregation on interstate buses as a violation of the interstate commerce clause. In December 1960, Boynton v. Virginia expanded the Morgan decision, outlawing segregated waiting rooms, lunch counters, and restroom facilities for interstate passengers. However, both rulings were largely ignored in the Deep South.

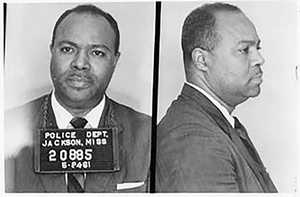

On May 4, 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began a racially integrated Freedom Ride through the South on Greyhound and Trailways buses as a way to test whether buses and station facilities were compliant with the Supreme Court rulings. The ride was met with unprecedented violence, including the burning of a bus in Anniston, AL and riots in Birmingham, AL and Montgomery, AL. Further Rides followed, organized by various groups and individuals, as a way to draw national attention to the harsh reality of segregation and put pressure on the federal government to enforce the law.

On September 22, 1961, after six months of protests, arrests, and press conferences by the Freedom Riders, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) finally outlawed discriminatory seating practices on interstate bus transit and ordered the removal of "whites only" signs from interstate bus terminals by November 1. Activists vowed to step up the pressure to enforce the ruling. While pockets of racist resistance persisted for several years, even segregationist Birmingham, AL had conceded the issue by January 1962.

The signs came down. More than simply a moral victory or a public relations coup, the victory won by the Freedom Riders changed the everyday lives of black travelers throughout the South, through the remainder of the 1960s and beyond.