The Power of the Press

The Freedom Rides were successful in large part because they were able to engage the media and gain a sympathetic national audience. A handful of reporters and photographers from the black press and one freelance writer affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) accompanied the Riders on the buses during CORE's original May 4 Freedom Ride. Other than these journalists, initial news coverage of the Rides was mixed or strongly negative. Early news accounts criticized "extremists on both sides," equating civil rights activists with their segregationist opposition. Other editorials characterized the Freedom Riders as "outside agitators," meddling in communities to which they did not belong — although many of the African-American Riders had been raised in the South.

The images and eyewitness accounts of May 14, 1961 changed the country's consciousness. Footage of a burning bus in Anniston, AL shocked the nation, as did photographs of the beatings inflicted during the riot at the Birmingham Trailways Bus Station and of the bandaged face of Freedom Rider James Peck lying in a hospital bed. These pictures were unlike anything that Americans had seen previously. Images brought home the brutality of the white segregationist regime in a way that words alone could not convey. Klan members attacked Birmingham Post-Herald photographer Tommy Langston along with other members of the media and attempted to destroy their film; miraculously, the roll of film inside Langston's smashed camera survived intact.

Similarly, the impassioned eyewitness account of Howard K. Smith, a native Southerner who had traveled to Birmingham to investigate allegations of lawlessness and racial intimidation from a neutral perspective helped shift public opinion. Just a few hours after the riot, he delivered his report over the national CBS radio network. Smith described a scene where "one passenger was knocked down at my feet by twelve of the hoodlums and his face was beaten and kicked until it was a bloody pulp." In the end, Smith abandoned journalistic objectivity, warning of "a dangerous confusion in the Southern mind" while calling for legal change and presidential action to improve the situation.

While accounts of the Freedom Rides in the white Southern press remained sharply negative and mocking, national media coverage became more favorable in the days that followed. Jim Peck gave an interview on NBC's Today Show. The June 2, 1961 issue of Time magazine featured the Freedom Rides as its cover story and was openly sympathetic in its coverage. Life magazine also chose the Freedom Riders as its "story of the week" for the June 2 issue, including powerful images from the siege of the First Baptist Church.

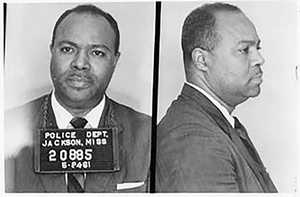

News reporters and photographers accompanied the Freedom Riders through most of the Rides' key events, from the May 21 riot and threatened mob violence in Montgomery, AL all the way to the tense National Guard escort through Mississippi on May 24 and the breach of peace arrests that followed upon the Freedom Riders' arrival in Jackson. Movement leaders of the 1960s quickly absorbed the Freedom Riders' example; the most effective and best-remembered campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement were those where the news media captured iconic images that the nation found impossible to ignore.