What Came Next

The Freedom Rides represented a major evolution in the tactics and strategy of the Civil Rights Movement. Movement leaders at the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Southern Christian Leadership Coalition (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) saw that nonviolent direct action could deliver results, even when met with determined and violent opposition from white supremacists inside and outside of local government. Thanks in large part to the phone calls and calm diplomacy of Nashville Student Movement leader Diane Nash, the Rides, initially a CORE project, became a coalition greater than any single organization's agenda — other groups knew the stakes of what CORE had put in motion and would not allow the campaign to fail. The Rides also marked an unprecedented level of engagement with the federal government and the beginning of a personal rapport between Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and movement leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Rides were an escalation in a nonviolent war, and that escalation would only continue. Efforts such as the SCLC's successful Birmingham Campaign of 1963, which curtailed segregation of public facilities in Bull Connor's Birmingham, AL and the SNCC and SCLC 1965 Selma to Montgomery Marches, calling for the passage of national voting rights legislation, used many of the same techniques as the Freedom Rides — pitting sympathetic activists (including children, in the Birmingham campaign) against violent segregationist foes while the world looked on.

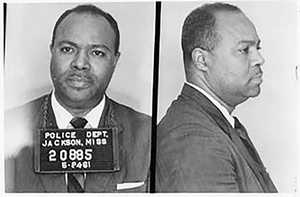

But the greatest impact of the Rides may have been the people who came out of them. In 1961, when Mississippi officials jailed Freedom Riders at Parchman State Prison on breach-of-peace charges, they hoped that the harsh conditions would break the Riders' spirits and squelch their movement. Instead, the experience proved to have the opposite effect — as prison became a crucible and training ground for the next generation of activists. John Lewis spoke at the March on Washington in 1963, played a pivotal role in organizing the Selma to Montgomery marches, and was elected in 1986 to the U.S. Congress. Stokely Carmichael became president of the SNCC in 1965 and would later coin the term "Black Power." Catherine Burks-Brooks was active in the Mississippi voter registration movement. These are just three names among many whose experiences on the buses and in jail prepared them for the Civil Rights struggles to come.

"We allowed the spirit of history to use us," said John Lewis in 2001, by demonstrating the willingness "to give a little bit of blood to redeem the soul of America."

In the years to come, greater prizes would be won: passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing racial discrimination in public and private facilities, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawing discriminatory voting practices, and with them the end of legally enforced segregation as a way of life. The cost would grow as well: more beatings, more jail time, and the murder of activists such as James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964 and Viola Liuzzo in Alabama in 1965. The Freedom Rides were a template and a training ground, forging new ties between groups and organizations while providing tangible evidence of what personal sacrifice could achieve.