In the last half of the 19th century, America underwent a series of changes. The Civil War brought tensions over slavery to a head, and resulted in thousands of deaths. Following the conflict, America's frontier saw new towns spring up along ever-expanding railway lines. A technological revolution had taken hold in the country's cities, with new factories employing thousands of Americans as well as a new influx of immigrants. Newly emancipated blacks in the South began to exercise their right to vote, but with the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, their rights and liberties began to crumble under the threat of violence. Amidst all of this, James Garfield was elected president, bringing hope to Americans of all backgrounds across the nation.

-

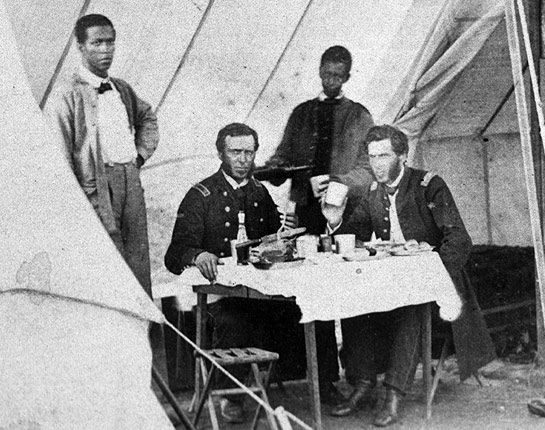

Weeks after Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the state of South Carolina voted to secede from the United States. Other southern states soon followed, and before Lincoln took office in February of 1861, the Civil War had begun. That August, James Garfield joined the Union Army and was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 42nd Ohio Infantry.

Credit: Western Reserve Historical Society -

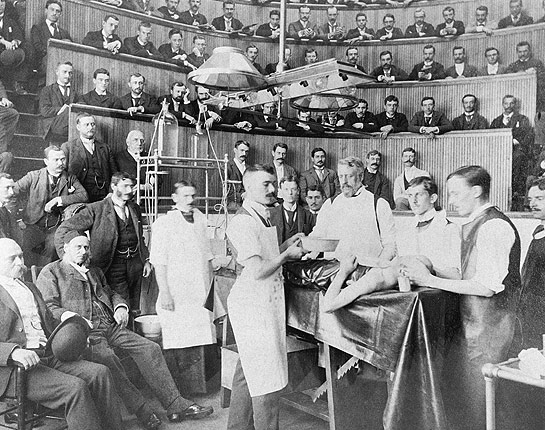

The Civil War was fought before the introduction of antiseptic medicine, and infection among wounded soldiers was common. But when methods of hand-washing and sterilization were introduced years later by Joseph Lister, battlefield surgeons like Dr. Willard Bliss, an acquaintance of James Garfield from Ohio, did not readily accept the new techniques.

Credit: National Library of Medicine -

More than 750,000 men died in the Civil War. Americans felt the profound loss deeply, and James Garfield was no different. He would later recall that when he came upon a group of men that looked as if they were sleeping, something went out of him that never came back – "the sense of the sacredness of life and the impossibility of destroying it."

Credit: Library of Congress -

By 1861, Americans were deeply divided on the issue of slavery. While some in the Union Army fought primarily to prevent the nation from being torn apart, James Garfield fought principally for emancipation. Though he considered himself rational in most matters, on the issue of abolition Garfield said that he had "never been anything else than radical."

Credit: Library of Congress -

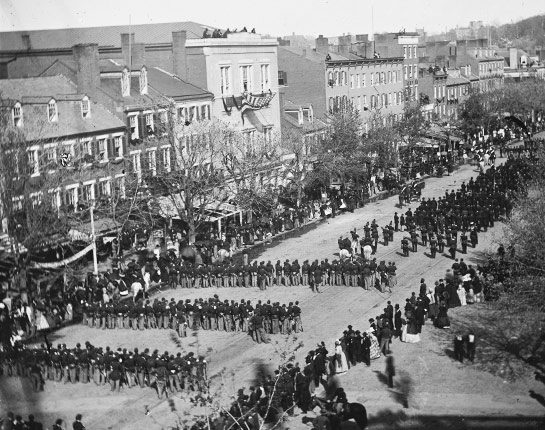

On April 15, 1865, Abraham Lincoln became the first President of the United States to be assassinated. Seen by many as a final chapter in the Civil War, the murder of a president shocked the nation. James Garfield, visiting New York at the time, wrote his wife Lucretia: "My heart is so broken with our great national loss that I can hardly think or write or speak…"

Credit: Library of Congress -

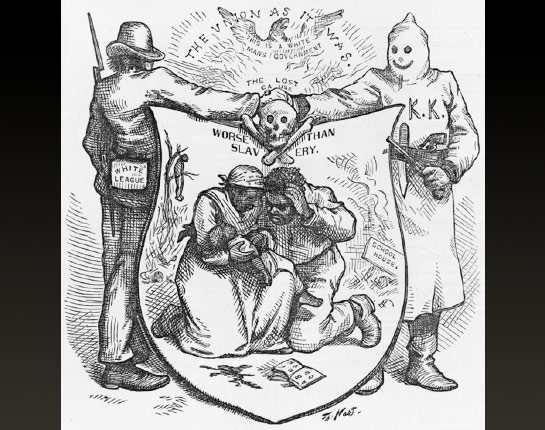

Following the Civil War, Garfield continued to fight in Congress for equality and opportunity for freed slaves. However, with the withdrawal of federal troops enforcing Reconstruction in 1876, the voting rights and liberties of freed blacks began to crumble under threat of violence.

Credit: Library of Congress -

With only 38 states in 1880, the United States was still a nation with a massive frontier. As pioneers pushed westward, immigrants helped increase the American population from 31 million in 1860 to more than 50 million in 1880. James Garfield grew up on the edge of the frontier in a log cabin in Ohio.

Credit: Getty Images -

After the Civil War, the United States was convulsed with change. A technological revolution was taking place, and miles of new railroad tracks connected the nation as never before. As historian Kenneth Ackerman observed: "the energy of war was now channeled into building railroads, factories, and mines."

Credit: Library of Congress -

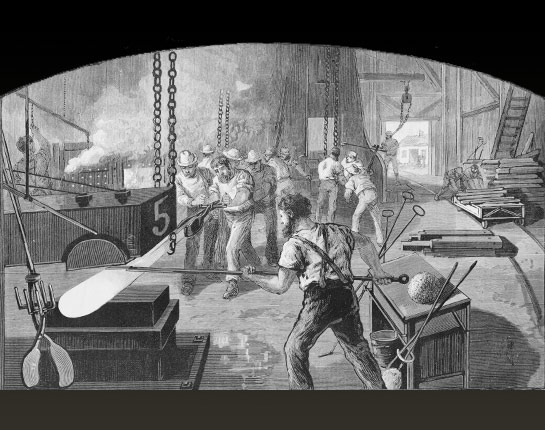

The burgeoning factory system boomed in the cities. For the first time, more Americans were living in cities than on farms. In the newly industrialized economy, millions of Americans worked in factories where fourteen-hour days, harrowing conditions, and starvation wages were common.

Credit: Corbis -

Though Garfield had grown up not in a city but on the frontier, he knew well what it was like to be poor. As the story of his rise from abject poverty came to be widely admired, Garfield wrote a friend, "I lament sorely that I was born to poverty…Let us never praise poverty."

Credit: Library of Congress -

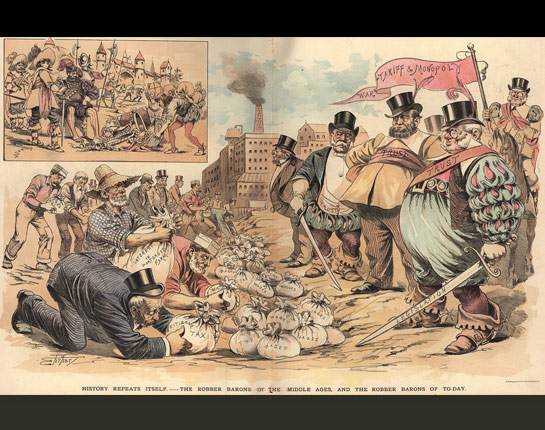

Factories were channeling unimaginable wealth to a growing aristocracy. By 1880, the inequalities of capitalism were so vast that they threatened democracy itself. This cartoon from the time likens the industrial leaders' exploitation of workers and influence over politicians to the robber barons from the Middle Ages.

Credit: Public Domain -

The widespread corruption of public officials was a common theme of political cartoons in the late 19th century. This cartoon portrays Roscoe Conkling pouring a power-drunk President Ulysses S. Grant a second term, a reference to Grant's bid to be the Republican nominee in the 1880 election.

Credit: Cornell University Library -

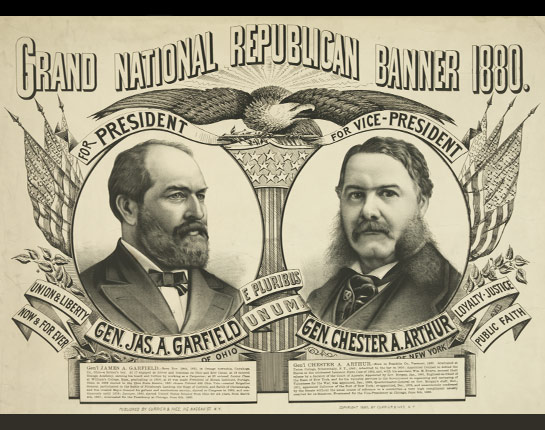

With rifts within the party on full display, the Republican National Convention of 1880 was the longest convention in Republican Party history. Garfield was not even a stated candidate until the 34th ballot was taken and delegates from Michigan put forward his name. Two ballots later, Garfield secured the nomination with 399 votes.

Credit: Library of Congress -

Hours later, Chester A. Arthur was officially chosen as Garfield's vice presidential running mate. Selected to appease the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party, Chester Arthur had never run for elected office prior to his nomination.

Credit: Library of Congress -

To many, Arthur and his fellow Stalwarts represented the corruption of the spoils system. Garfield, on the other hand, was seen as a presidential candidate who could and would reform what people saw as a broken system of government.

Credit: Corbis -

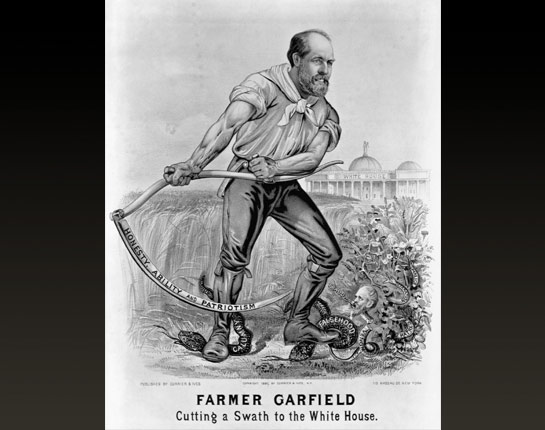

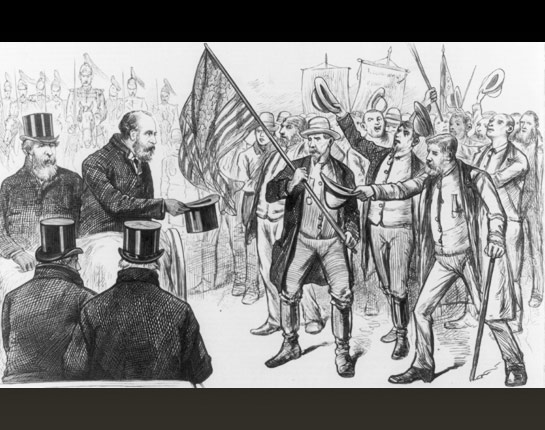

As was custom at the time, Garfield did not campaign much on his own behalf, instead, he spent time on his farm in Mentor, Ohio, where people from across the nation would come to talk with him on the porch. After Garfield's nomination, a group of black voters gathered to celebrate on his lawn.

Credit: Hiram College Archives -

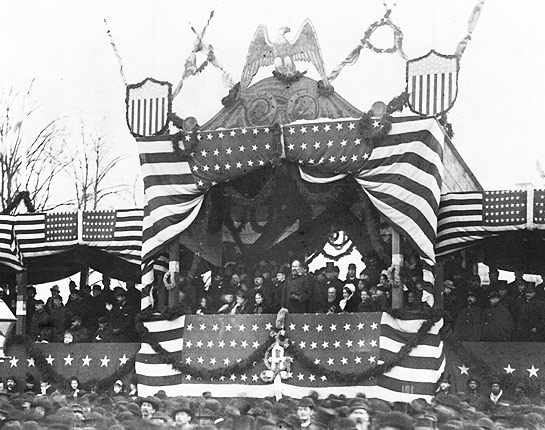

James Garfield became the 20th President of the United States on March 4, 1881. His mother Eliza, who gave him $17, her life savings, to go to school in 1848, became the first mother of a president to attend her son's inauguration.

Credit: Library of Congress -

Garfield's presidency gave a voice to the common man. Poor people, freed slaves, even Confederate soldiers, depicted here saluting President Garfield, felt a kinship with Garfield. As biographer Candice Millard wrote, "Although he had been elevated to the highest seat of power, he was still, and would always be, one of their own."

Credit: Library of Congress -

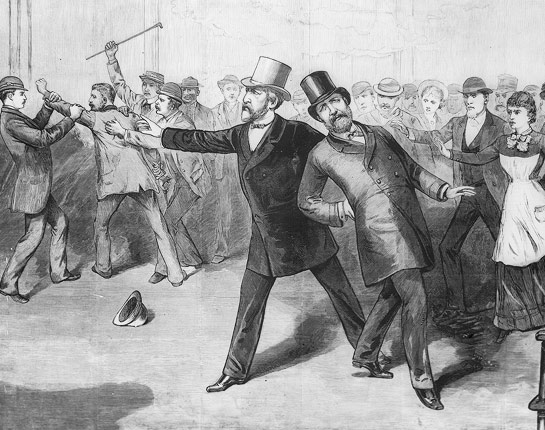

On July 2, 1881, Charles Guiteau shot President Garfield in a train depot in Washington, D.C. At the time, neither Americans nor their presidents believed that presidential protection was necessary. They believed that political violence was unnecessary in a democracy where people had the chance to voice disapproval with their vote.

Credit: Library of Congress -

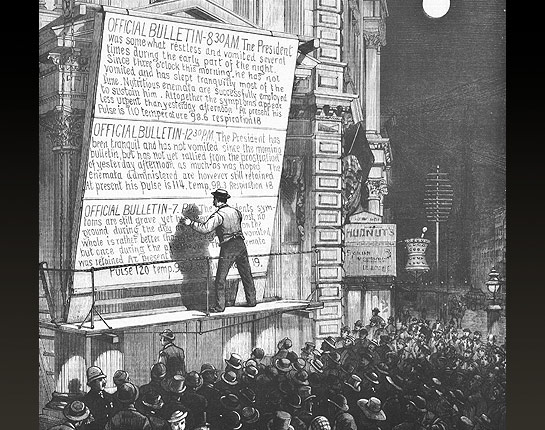

Lying on the floor of the station, Garfield dictated a telegram to Lucretia. The telephone, invented only five years earlier, was not yet a part of daily life, but with advances in the telegraph and improved printing technologies, news traveled faster than ever before. Americans, reeling from the attack, expected regular updates on Garfield's condition.

Credit: University of Virginia Library, Special Collections -

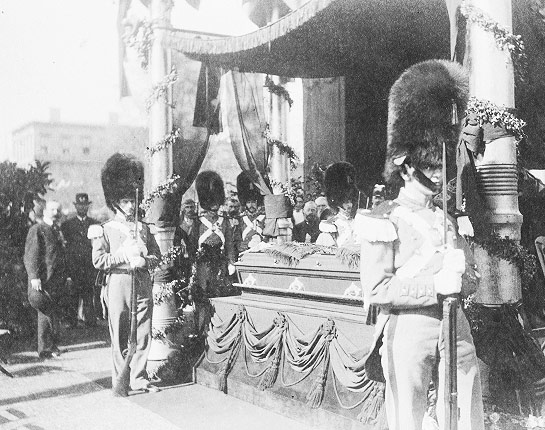

An estimated 250,000 people walked past President Garfield's coffin on display in Cleveland, Ohio before Garfield was buried there on September 26, 1881. The population of Cleveland at that time was 150,000.

Credit: Western Reserve Historical Society -

The White House, like all of Washington, was draped in mourning bunting. President Garfield's daughter Mollie wrote in her diary: "Even the shanties where the people were so poor that they had to tear up the clothes in order to show people the deep sympathy and respect they had for Papa…All persons are friends in this deep and great sorrow."

Credit: White House Historical Association -

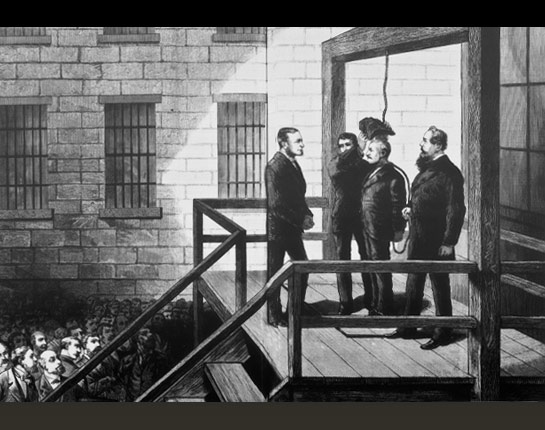

After Garfield's death, Charles Guiteau was put on trial. While his lawyers made his case one of the first to use the insanity defense, Guiteau himself blamed Garfield's doctors for the president's death. The American people had very little sympathy for either defense. Guiteau was found guilty and was executed on June 30, 1882.

Credit: Public Domain -

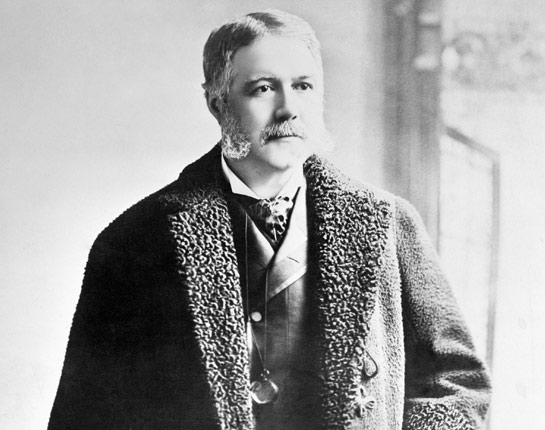

After the assassination, Americans turned their anger to the spoils system—the system that bred Guiteau's vengeance. Chester Arthur, his own career owing much to the spoils system, became an unlikely champion of reform after he became president on September 20, 1881. He signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883.

Credit: Corbis -

Dr. Bliss, whose unsterile treatment of Garfield's wound caused the infection that killed the president, never regained his reputation. In the years following Garfield's death, the American medical establishment began to accept Joseph Lister's practice of antiseptic medicine. Here, doctors demonstrate antiseptic surgery practices in 1898.

Credit: Corbis