To understand the people who've profoundly impacted history, we're exploring the books that profoundly impacted them. Here, Andrew Carnegie biographer David Nasaw tells us about the industrial titan’s love of a Scottish poet, interest in American history, and devotion to a surly English philosopher.

By David Nasaw as told to Cori Brosnahan

He came to this country in 1848 at the age of 13. He’d spent a couple of years in elementary school, but no more than that. And he was voraciously curious. He came from Scottish artisans who were very involved in politics and social questions. In Scotland, he’d listened to his father and his friends debate chartism and socialism. When he got to this country, he took up a debate with his cousin about the benefits of American democracy versus the British commonwealth, the monarchy. And he just began reading. One of his lifelong commitments was to libraries, because without libraries he would never have been able to educate himself.

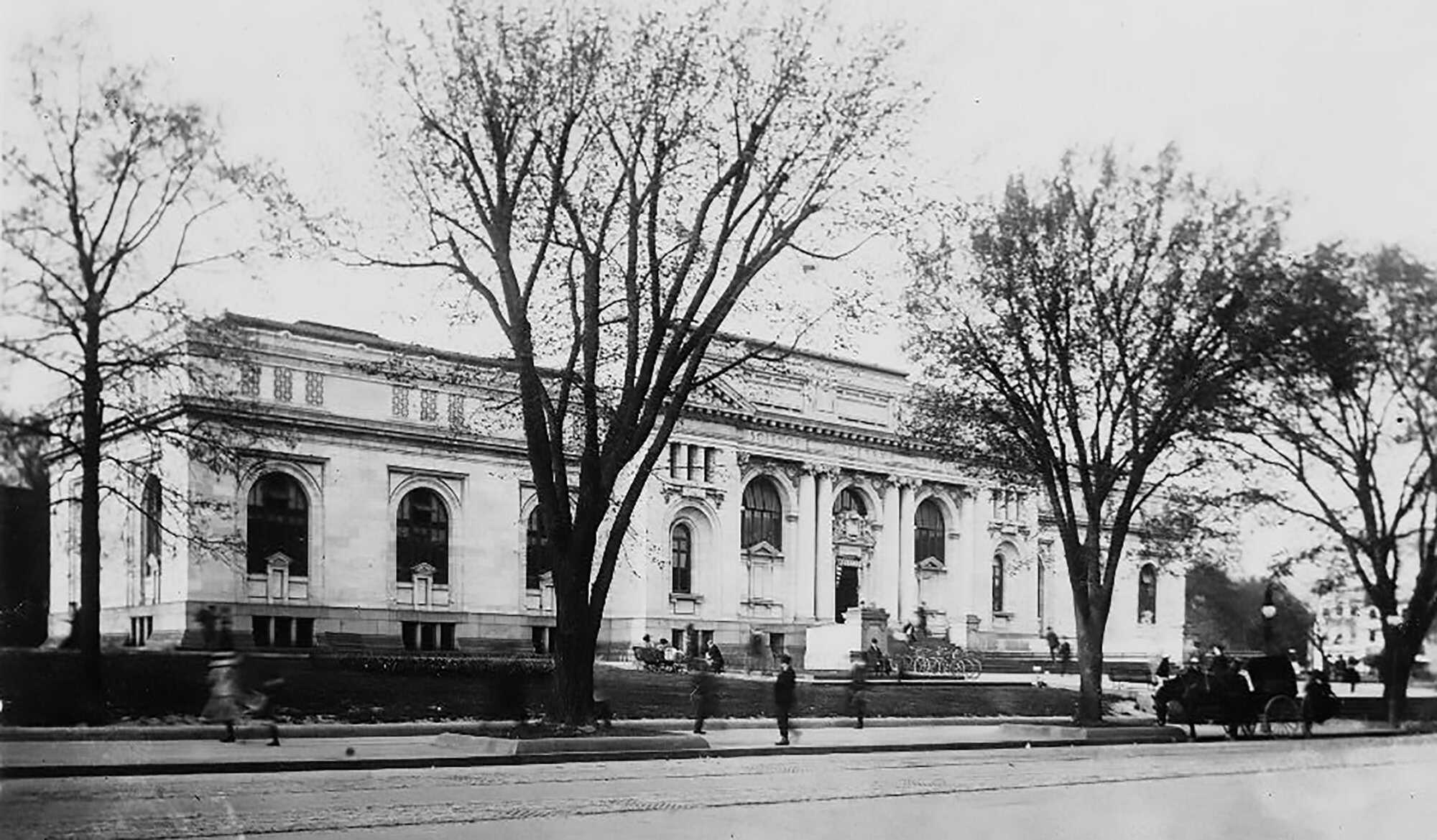

There’s this remarkable story I tell in my book about how the only real open library in Pittsburgh at the time was an “apprentice’s library.” It was in a private home. Carnegie was turned away because although he was 17 years of age, he wasn’t an apprentice — he had a real job as a messenger boy. But he protested. He wrote letters to the newspaper until he was finally allowed to borrow books from this library. Anyway, he read extensively in literature — but more than that, in politics and in history, trying to figure out how and why American democracy came to be.

All his life, he believed in reading. And he was most enthusiastic about getting working people — the people that worked for him — technical educations. He believed that in order to better themselves, metal workers had to know about metallurgy, about engineering, about physics. And they needed access to the best scientific journals that were available. So attached to his first iron mill, he set up a library.

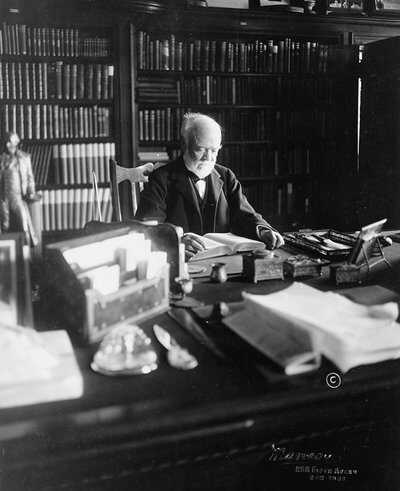

He moved to New York, and by the time he was in his 40s, he was a millionaire. Very early in his life he went into a kind of semi-retirement. He joined all sorts of literary salons and made good friends with the intellectuals in New York. He believed that if a man devoted himself only to business, he wouldn’t be very good at business and he wouldn’t be a very good man. I’m sure he read everyday. He probably read not only the newspapers, but the important journals of the day — the equivalent of our New Yorker, and The Atlantic, and Harper’s.

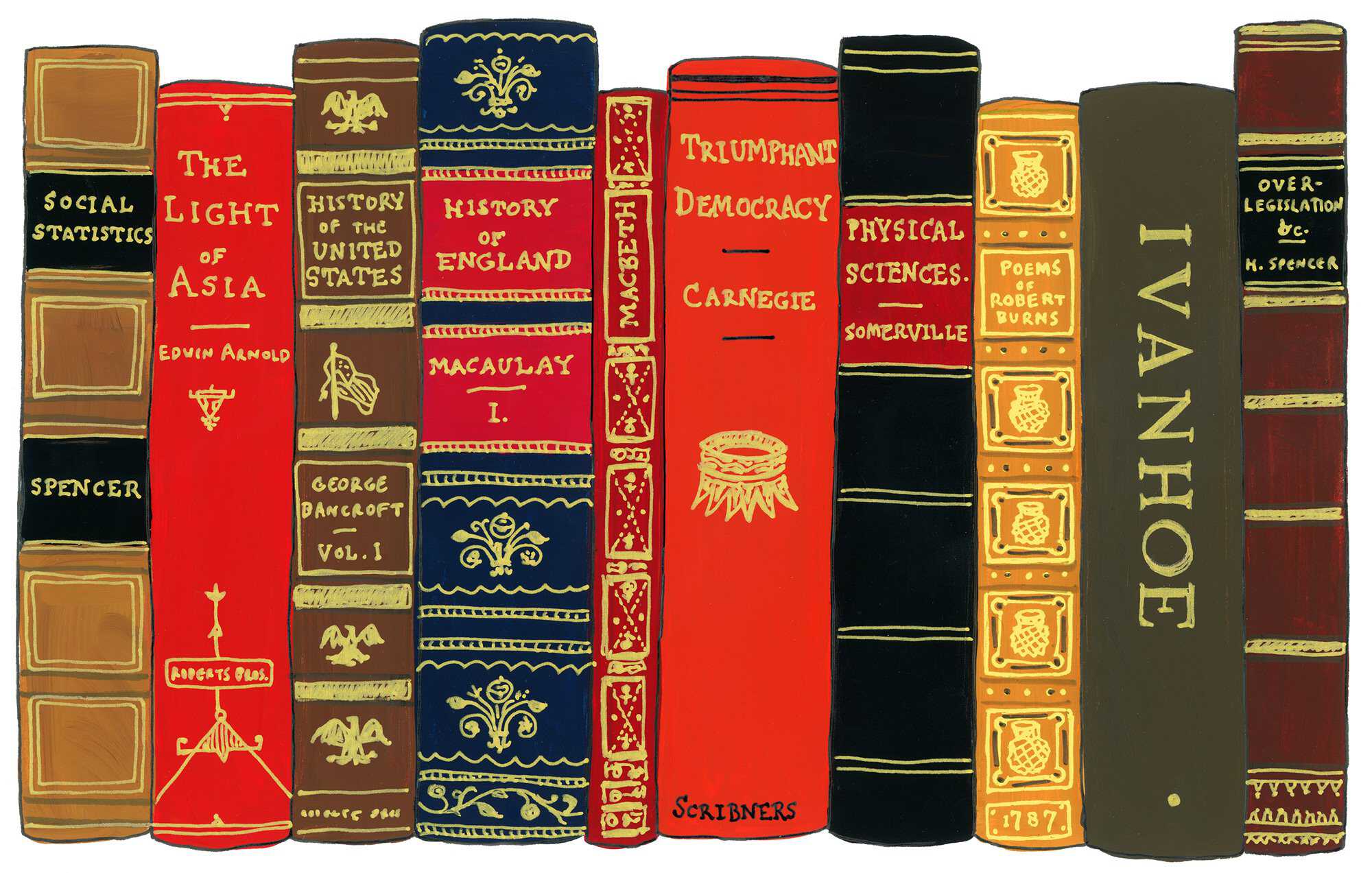

He loved poetry. He absolutely adored Robert Burns — who was like a Scottish folk hero and a rockstar. Every kid memorized some Robert Burns and some Shakespeare. And Carnegie probably knew more Robert Burns than most. It’s old-fashioned rhyme poetry — it’s very romantic. Carnegie always referred to himself as the star-spangled Scotsman. He was comfortable on both sides of the ocean.

He also loved historical fiction like Sir Walter Scott. He read people like Thackery and Bret Harte and Emerson. He knew British literature and American literature. His courtship with his wife Louise supposedly began with Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia, about the life of Buddha. They read it to one another. He also read his friends — among them Mark Twain, Matthew Arnold, and Herbert Spencer.

Spencer was a famously ugly, grumpy Englishman. He didn’t get along with anybody. Carnegie kind of wormed his way into his good graces. He bought him a piano. He tried to visit him. He flattered him. Spencer was the greatest philosopher of his time. It was he who coined the term “survival of the fittest.” He was the first social Darwinist. And he, Spencer, gave Carnegie and other millionaires a sort of rationale for their ruthless appetite for making money. Because he essentially said, only the fittest survive, and we have to let the fittest do whatever they want to do because they bring civilization forward.

Carnegie was an intellectual. He was always trying to figure out how the hell a poor guy like himself ended up with all these millions. He wasn’t a churchgoer. He didn’t believe in divine intervention. It was Herbert Spencer who really gave him an answer to his questions.

He traveled all over the world. He read about the countries he traveled to before he got there and afterwards. He wrote about those travels, too. People loved his travelogues. His later writing was not as popular because it was much harder-edged. It was about peace, the peace process, and the end of war. And it was about the responsibility that rich men had to their communities. So he pissed a lot of people off.

He thought of himself as a wise man, as a learned man. [Of the books he wrote], I think one of his favorites would have been the Gospel of Wealth and another would have been the Triumphant Democracy. But probably the Triumphant Democracy would be the one he was most proud of. He worked really hard at it. It was his gift to his inherited country. [It was about] how the future was going to be democracy — how democracy was stronger politically and economically. And he explained why.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. David Nasaw’s book Andrew Carnegie was used as an additional resource.

Published January 2018.