Biography: Ulysses S. Grant

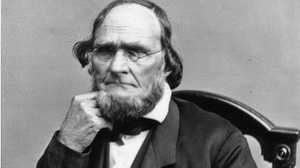

For much of his life, Ulysses S. Grant failed at every occupation he tried. But in the United States Army, his remarkable talents as a soldier and leader saved his country from falling apart.

Born April 27, 1822, Hiram Ulysses Grant, as he was named, grew up in Georgetown, Ohio. His childhood was, he recalled, an "uneventful" one. He went to school, did chores, ice skated, fished, and rode horses, like other children on the American frontier. Grant's father, Jesse Root Grant, owned a tannery, but his son hated the horrible stench and the filth of the family business. From a very young age, Hiram showed a remarkable talent for working with horses. His father allowed him to earn his keep by plowing, driving teams to haul wood, and performing other chores.

Jesse Grant realized early on that Hiram would never make it as a businessman. In 1839 Jesse sent the boy to the United States Military Academy at West Point, ignoring the fact that the small, skinny 17-year-old did not want to go. Upon his arrival at West Point, Grant discovered that there was no one by his name listed as a new cadet. But there was a U. S. Grant on the list. Rather than risk refusal, young Grant changed his name on the spot. Ulysses S. Grant was born.

U. S. Grant showed little promise at West Point. Although relatively well educated, he studied little. He stood out in mathematics and horsemanship, which had always been his best subjects, as well as in art. He earned his lowest marks in French. Ulysses graduated 21st out of 39 cadets in his class. Like many graduates, he planned to resign from the military after serving his tour of duty.

After graduation, Grant was stationed in St. Louis, Missouri. There, he visited a West Point roommate, Frederick Dent. Soon, Grant began courting Julia Dent, Fred's sister. The two quickly fell in love. In 1844 Julia accepted Ulysses' marriage proposal. But before they could marry, Ulysses went off to war for the first time.

In later years, Grant wrote that the Mexican War was "one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation." Officially, he served as a quartermaster, efficiently controlling the movement of supplies. But he also saw action, and showed bravery under fire. Grant also took the opportunity to study generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor carefully, learning from their successes and their failures.

For a time after the war, Grant, his wife, and their firstborn son, Fred, enjoyed happiness. But in 1852, when Ulysses was transferred to Fort Vancouver in what is now Washington State, trouble began. He missed Julia and their two young sons, one of which he had never seen. Grant lost money in business ventures. He grew despondent and began to drink. A transfer to a post in California did little to raise his spirits. On April 11, 1854, Grant resigned from the Army.

Ulysses moved with his family to Missouri, and began to farm land given to him by Julia's father. Grant called the farm Hardscrabble, a name that fit. He built a modest house there, planted potatoes, corn, and oats, and struggled to survive. By 1857, after several bad years, the farm had failed. Grant moved to St. Louis, where he failed at several pursuits. Ulysses then moved his family to Galena, Illinois, where he took a job as a clerk in his father's leather goods shop.

Shortly after the Civil War started in 1861, Grant once again became a soldier. As a battlefield commander, he won the Union's first major victory, capturing Fort Donelson in Tennessee and demanding the rebels' unconditional surrender. He successfully turned back a surprise Confederate attack at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. His capture of the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi on July 4, 1863, after a drawn-out siege, broke the Confederate stranglehold on the Mississippi. Grant had finally found an arena where he could shine: the battlefield.

In March 1864, a grateful Abraham Lincoln appointed Grant commander of all the U.S. armies, with the rank of lieutenant general. No soldier since George Washington had held the rank. As commander, Grant worked to constantly occupy Robert E. Lee's rebel army in the East, while Union troops struck at the heart of the South, destroying homes, farms, and factories — and Southerners' willingness to fight. Grant's plan worked, and on April 9, 1865, he accepted Lee's surrender. Four bloody and tragic years of Civil War ended, and Grant was the hero who had achieved the victory.

In 1868, with the nation still struggling to heal the wounds of war, Grant accepted the Republican presidential nomination. Running under the slogan "Let Us Have Peace," Grant defeated Democrat Horatio Seymour. During two terms in office, Grant worked hard to bring the North and the South together again, contending with an emerging white supremacist group called the Ku Klux Klan, and violent uprisings against blacks and Republicans. He met with Native america leaders, including Red Cloud, trying to develop a peace policy in the West. He also took steps to repair the damaged economy. But his two terms as president are best remembered for financial scandals among members of his party and his administration.

In 1877, after he left office, Grant traveled with Julia on a round-the-world tour. He was the most famous American of his time. In city after city, Grant was welcomed by cheering mobs — and by world leaders, including Queen Victoria and the Emperor and Empress of Japan. After returning to the United States, the Grants moved to New York. There, Ulysses began to put his money into Grant and Ward, a Wall Street investment firm co-owned by his son Buck. Ulysses didn't know that Ferdinand Ward, the firm's other partner, was stealing investors' money. In 1884 the firm went bankrupt. So did Ulysses S. Grant.

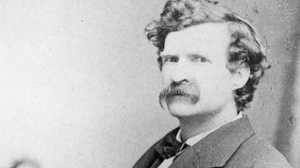

Desperate for money, Grant turned to writing his wartime memoirs as a way to support his family. He began by selling short magazine articles, then negotiated a book contract with a publishing company owned by his friend, the novelist mark Twain. Published as a two-volume set, Grant's memoirs sold some 300,000 copies and became a classic work of American literature, but Grant never saw any of the profits. Shortly after he had begun to write, Grant had been diagnosed with throat cancer. He died on July 23, 1885, just two months after the book went to press, and was honored with an enormous funeral procession in New York City.