Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

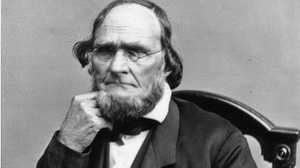

As a soldier, General Ulysses S. Grant had depended upon the able assistance of Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian. As president, Grant tried with little success to ensure peaceful relations with Native Americans. Many Americans saw Indians as little more than animals that stood in the way of progress, and favored their extermination. But not Grant. At his inauguration, Grant said that he would "favor any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship."

After taking office, Grant named Parker head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He received a delegation of Native Americans at the White House, including the Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud. He advanced a policy of peace. Grant also abided by the provisions of the second Fort Laramie Treaty, which gave the Lakota Sioux possession of much of Montana, Wyoming, and what is now South Dakota. But when gold was discovered in those hills, whites rushed to the territory, and clashes between Native Americans and whites began. The man who started it all was a career soldier named George Armstrong Custer.

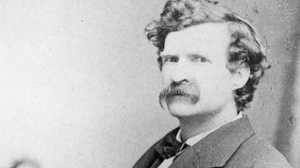

Custer had already gained a reputation for getting into trouble. He graduated from West Point last in his class. Just after his graduation, he was court-martialed for failing to stop a fight between two cadets. But by then the Civil War had broken out, and the Army needed all the officers it could get. Custer went unpunished.

Custer distinguished himself in several Civil War battles. After the war, he went West, where he led the Seventh Cavalry in a successful campaign against the Southern Cheyenne Indians. In 1867, Custer was court-martialed again, this time for leaving his post without permission. The Army suspended him for a year without pay. But as trouble with the Indians grew, he was returned to duty.

In 1874 Custer led an expedition in Lakota Sioux territory, in the Black Hills of Dakota. There, he confirmed the presence of gold -- and started a gold rush, which would soon cause trouble between Native Americans and white miners. Grant tried to honor the Treaty of Fort Laramie, but miners pressured him to let them search for gold in the sacred hunting grounds of the Sioux and Cheyenne.

Grant gave in to the pressure. The federal government issued an order requiring all Indians to move onto reservations by January 31, 1876, or be considered hostile. But many Indians did not hear the order or simply ignored it. Grant decided to send troops under generals John Gibbon, George Crook, and Alfred Terry to Dakota to fight the Sioux. At first, Custer was not included as part of the force.

Grant's reason for avoiding Custer was political. Custer had testified about corruption in Grant's Indian affairs offices, so Grant removed him from command. But Grant's wartime friend Phillip Sheridan persuaded him to send Custer West. For Custer, the move would prove fatal.

In June 1876, as sightseeing crowds flocked to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, U.S. troops in Montana and Dakota began a multi-pronged attack on the Indians who had not gone to reservations. Custer arrived in Indian Territory first. Instead of waiting for forces under Generals Crook and Terry, Custer led little more than 200 men in an attack on the Sioux Chief Sitting Bull's camp on Montana's Little Bighorn River.

In the fight that followed, a force of thousands of Sioux killed Custer and all of his men. Shock and outrage over what was called "Custer's Last Stand" hastened the government's campaign against the Indians. By the following year, the Sioux had been forced to retreat into Canada. In death, Custer became a hero, the subject of songs, books, and poems. Ironically, the man who had led an attack on a peaceful Sioux village was remembered as the victim of a massacre.

Consideration of Native Americans's rights would not reawaken until the 1880s, when leaders like Mary Bonney took up the cause.