Julia Dent Grant

In her later years, Julia Grant tended to portray her childhood as something out of a dream. And although her real-life marriage to Ulysses S. Grant would deliver all the romance and adventure she could ever have wanted, she would have to suffer loneliness and hardship along the way.

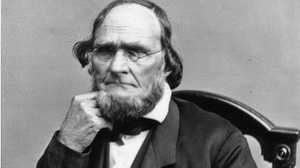

Born in 1826, Julia was one of seven children born to Frederick and Ellen Wrenshall Dent. Her father, known as Colonel Dent, owned a plantation called White Haven, 12 miles from St. Louis, Missouri. While Julia probably enjoyed a pleasant childhood, she tended to depict it as perfect, ignoring the fact that her mother disliked living on a farm.

In February 1844, Julia met Ulysses S. Grant during one of his frequent visits to White Haven. Grant and Julia's older brother Fred had recently graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point. The two men had been roommates in their final year. Although she was not pretty, Julia quickly won the heart of the ruggedly handsome Grant. Ulysses admired her spirit, and Julia shared his love of horses.

After just four months of courtship, "Ulys," as Julia called him, proposed marriage, and Julia accepted. For a year, the two kept their engagement a secret, but in 1845 Ulysses officially asked Colonel Dent for his daughter's hand. The Colonel approved the match, but the wedding had to wait. Trouble was brewing on the U.S. Mexican border. Soon, Ulysses would be fighting in his first war.

Although Julia must have worried for her beloved's safety, he wrote her regular letters. In them he told her about the things he saw before and during the Mexican War. He also reminded her how much he loved her. After a four-year separation, Grant returned to White Haven. At last, on August 22, 1848, Julia and Ulysses were married. They honeymooned in Louisville, Kentucky, on the first trip Julia had ever taken from her family home.

In November 1848, Julia left White Haven to become an Army wife. On May 30, 1850, she gave birth to her first child, a boy she and Ulysses named Frederick Dent Grant. The next few years were happy ones for Julia. It wasn't the places the Grants lived -- army bases in Detroit and Sackett's Harbor, New York — that made Julia happy. It was the fact that she and Ulysses were together. But soon, they faced another separation.

Ulysses spent two years stationed on the Pacific Coast. When Ulysses resigned from the Army in 1854 and returned home, Julia was probably glad to see him — and to present him with their second son, Ulysses, Jr., who was born while he was away. But it would be some time before she would enjoy anything close to happiness again.

In the world outside the Army, Ulysses failed at everything he did. He tried his hand as a farmer, and as a rent collector. He failed at both. When the Grants' farm and a job in St. Louis failed, Julia moved with Ulysses and their children to Galena, Illinois. There, Ulysses took a job in his father's harness shop.

Julia may have resigned herself to a life of struggle, but the Civil War changed everything. Her husband Ulysses became a national hero. And this time, Julia spent as much time as she could in camp with her husband. Both Grants were reluctant to face the separations they'd endured in the past. Julia's presence helped keep Ulysses on an even keel — and helped him stay away from alcohol, which had been an enemy since his days on the Pacific Coast.

After the war, Julia enjoyed the prosperous life she had always longed for -- first as wife of the commander of the armed forces and then as the First Lady. She was well liked in that role, and journalists remarked on her "propriety and dignity." During Ulysses' two terms in the White House, Julia entertained lavishly, playing hostess to dignitaries from around the country and the world. She enjoyed a meaningful friendship with Julia Fish, wife of secretary of state Hamilton Fish, who helped Julia overcome her country manners. And she endured the pain when corruption in her husband's administration damaged his reputation.

Julia dreaded leaving the White House at the end of Ulysses' second presidential term. But the glory days were not yet over. Just two months later, in May 1877, she and Ulysses embarked on a trip around the world. In country after country, enthusiastic crowds mobbed them. The Grants met the world's political leaders, and served as guests of honor at state banquets. After all the Grants had endured, it must have seemed a dream.

The Grants returned to the U.S. in 1879. But the high living soon came to an end. The Republicans failed to nominate Ulysses for a third term in office. Grant's investments in a financial firm co-owned by his son Buck were stolen by Buck's partner, a swindler. In desperation, Grant signed a lucrative contract to write his memoirs, but by then, he was already dying of throat cancer. Julia stayed beside Ulysses until he died, on July 23, 1885.

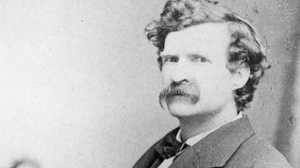

As the widow of one of the century's most famous men, Julia worked hard to make sure people remembered her husband fondly. The publication of Ulysses' memoirs, arranged by Mark Twain, provided her with a large sum of money, and she moved to Washington, D.C., the city that she loved. Julia's daughter Nellie and three grandchildren came to live with her there. Like her husband, the former first lady wrote her memoirs, but they would not be published until 1975. Julia Grant died in Washington on December 14, 1902, at the age of 76. She was laid to rest in Grant's Tomb in New York, alongside her husband.