The Mexican American War

In 1844, President James K. Polk ran on a Democratic platform that supported manifest destiny, the idea that Americans were predestined to occupy the entire North American continent. The last act of Polk's predecessor, John Tyler, had been to annex the Republic of Texas in 1845. Polk wanted to lay claim to California, New Mexico, and land near the disputed southern border of Texas. Mexico, however, was not so eager to let go of these territories.

Polk started out by trying to buy the land. He sent an American diplomat, John Slidell, to Mexico City to offer $30 million for it. But the Mexican government refused to even meet with Slidell. Polk grew frustrated. Determined to acquire the land, he sent American troops to Texas in January of 1846 to provoke the Mexicans into war.

When the Mexicans fired on American troops in April 25, 1846, Polk had the excuse he needed. He declared, "[Mexico] has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil," and sent the order for war to Congress on May 11.

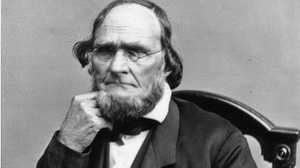

The act was a questionable one. Many Northerners believed that Polk, a Southerner, was trying to gain land for the slaveholding South. Other Americans simply thought it was wrong to use war to take land from Mexico. Among those was Second Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant. Although during the war he expressed no reservations about it, he would later call the war "one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory."

Despite arguments over whether the war was right, Americans had tremendous success on the battlefield. Young officers like Grant and Robert E. Lee, who would later lead armies against one another in the Civil War, had their first combat experiences in Mexico. Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott won a series of remarkable victories against the Mexican armies. This success was in spite of the fact that Mexican troops outnumbered the Americans in most cases. In September of 1847, after a masterful overland campaign, American troops under Scott captured Mexico's capital, Mexico City, and the fighting ended.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo sealed the American victory in 1848. In return for $15 million and the assumption of Mexican debts to Americans, Mexico gave up its hold over New Mexico and California. The enormous territory included present-day California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado and Wyoming. Mexico also agreed to finally relinquish all of Texas, including the disputed area along the border. The U.S. Congress approved the treaty on March 10.

Although the Mexican War had been won, the conflict over what to do with the vast amounts of territory gained from the war sparked further controversy in the U.S. The question over whether slavery would spread to these new territories would drive North and South even further apart.