The Panic of 1873

Since the end of the Civil War, railroad construction in the United States had been booming. Between 1866 and 1873, 35,000 miles of new track were laid across the country. Railroads were the nation's largest non-agricultural employer. Banks and other industries were putting their money in railroads. So when the banking firm of Jay Cooke and Company, a firm heavily invested in railroad construction, closed its doors on September 18, 1873, a major economic panic swept the nation.

Jay Cooke's firm had been the government's chief financier of the Union military effort during the Civil War. The firm then became a federal agent in the government financing of railroad construction. The railroad industry involved a huge amount of money — and risk. Building tracks where land had not yet been cleared or settled required land grants and loans that only the government could provide.

The nation's first transcontinental railroad had been completed in 1869. Entrepreneurs planned a second, called the Northern Pacific. Cooke's firm was the financial agent in this venture, and poured money into it. On September 18, the firm realized it had overextended itself and declared bankruptcy.

Mirroring the firm's collapse, many other banking firms and industries did the same. This collapse was disastrous for the nation's economy. A startling 89 of the country's 364 railroads crashed into bankruptcy. A total of 18,000 businesses failed in a mere two years. By 1876, unemployment had risen to a frightening 14 percent.

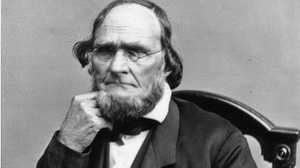

An economic cloud settled over Ulysses S. Grant's second term, and he tried to find a solution that would drive it away. Workers and businesspeople argued over what should be done. Grant — setting a course that would become the hallmark of the Republican Party -- sided with eastern business leaders, and adopted their ideas for easing the crisis. But when Grant left office in 1877, the cloud remained.

That same year, the depression set off railroad strikes. Workers all over the country, in response to wage cuts and poor working conditions, struck and prevented trains from moving. President Rutherford B. Hayes was forced to send federal troops to more than a half dozen states to stop the strikes. In the end, the fighting between strikers and troops left more than 100 people dead and many more injured.

Southern blacks suffered greatly during the depression. Preoccupied with the harsh realities of falling farm prices, wage cuts, unemployment, and labor strikes, the North became less and less concerned with addressing racism in the South. White supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, which had been suppressed through punitive Reconstruction legislation starting in 1868, resumed their campaign of terror against blacks and Republicans. Violent conflicts erupted, including 1873's Colfax Massacre in Louisiana. By the time the depression lifted in 1879, southern whites would already be regaining power.