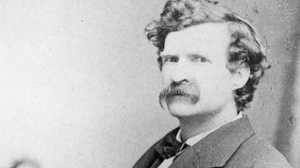

Charles Sumner

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts made a name for himself as an advocate of liberal causes. His outspoken support of abolition and the rights of emancipated blacks, and his calls for punishment of the defeated South, drew both praise and criticism -- and almost cost him his life. Such positions also made for a difficult relationship with President Ulysses S. Grant.

Born in Boston on January 6, 1811, Sumner graduated from Harvard Law School in 1833. Elected to the United States Senate in 1852, he served for more than 20 years. During the pre-war years, Sumner fought hard for abolition. He spoke out against proposals such as the Missouri Compromise, which kept the North and South at peace but allowed slavery to spread.

Sumner's opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act nearly killed him. In a Senate speech in May 1856, he blasted the bill. Sumner accused the bill's authors, Senators Andrew P. Butler and Stephen A. Douglas, of supporting slavery. Two days, later, South Carolina Congressman Preston S. Brooks, the nephew of Andrew Butler, attacked Sumner in the Senate and beat him severely with a cane. It took Sumner almost three years to recover from the beating.

After the Civil War, Grant, President Andrew Johnson, and others believed the wounds of war could be healed best by treating the South leniently. But Sumner belonged to a group called the Radical Republicans, who thought the South should be punished. Sumner proposed forcing Southern states to guarantee voting rights to African Americans before being readmitted to the Union, but could not gain enough support for his plan.

When Grant took office in 1869, Britain and the United States had not yet ironed out financial claims arising from the Civil War. During the war, Confederates had built a number of battleships in British shipyards. These ships, including theAlabama, had been used to try to break the Union blockade of the South and to harass and destroy Union merchant ships. The United States wanted Britain to pay for the damages, but negotiations had been difficult.

Sumner, then chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, insisted that the British pay not only for ships and merchandise the Confederates had destroyed, but for what he called "indirect damages" as well. Grant's secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, wanted the British to pay $48 million for the damages. Sumner's figure was more than $2 billion and he also wanted the British to apologize for their actions. In the end, Sumner only got part of what he wanted — the apology. Britain paid the United States a mere $15 million.

Sumner also clashed with Grant — this time successfully — over Grant's plan to annex the Dominican Republic. Grant saw the annexation as a way to solve two problems. The all-black nation would provide a haven where freed slaves could live in peace — without being harassed by angry Southern Whites. And the Dominican Republic not only contained valuable natural resources, but was a market for American goods as well.

Sumner vigorously opposed Grant's annexation plan. He felt that African Americans should be protected from Southern wrath instead of being forced to move away. In a scathing Senate speech, Sumner also pointed out that annexing the Dominican Republic would dissolve one of only two black-led nations in the Caribbean. It was, he said, a matter of a large, powerful nation picking on a weak defenseless one.

In the end, Sumner won out, and the Senate voted against Grant's plan. But Sumner's victory proved costly. In retaliation, Grant removed Sumner's friend John Lothrop Motley from his position as minister to London. Grant also succeeded in having Sumner removed from his post as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner continued to serve in the Senate, however, until his death in Washington on March 11, 1874.