Not Just a Normal School Yearbook

Photos capture the experience of Leland, Mississippi’s first integrated high school class.

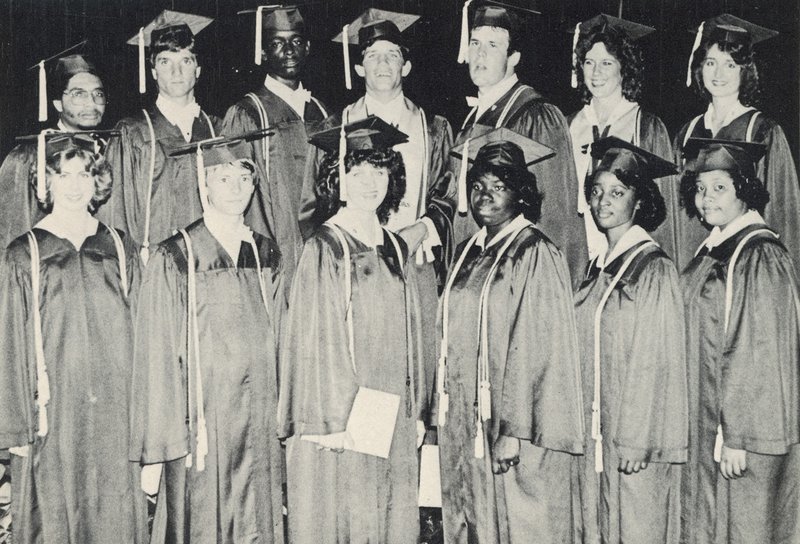

In the fall of 1970, a new class of Leland, Mississippi children entered the first grade. They were pioneers in a radical social experiment—mandated by the Supreme Court’s 1969 Alexander v. Holmes ruling—that saw the first fully interracial cohort in that small southern town attend the same public schools. Over the next 12 years, those children were together in the classroom and on the playing fields, in clubs and in the cafeteria. In addition to the customary trials and triumphs of growing up, they navigated a complicated social order within and outside of school. Many of them observed that while court rulings had made segregation illegal, invisible and unspoken divisions persisted beyond the school’s walls.

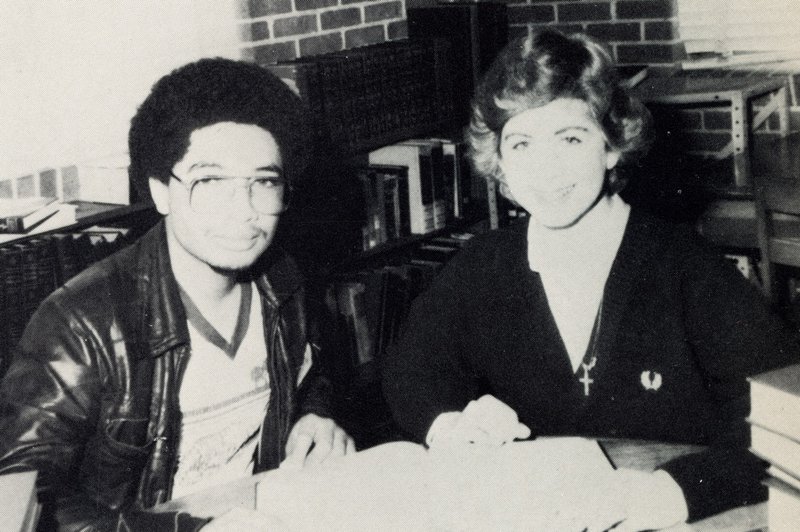

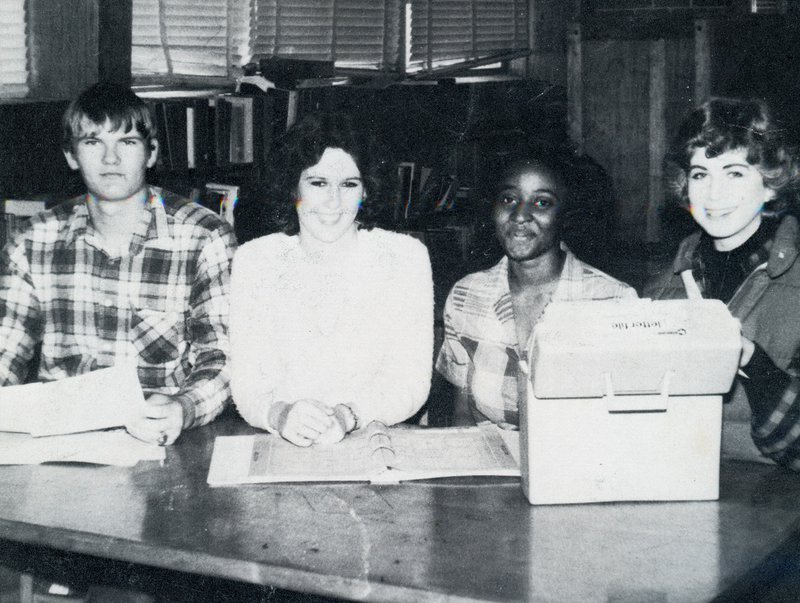

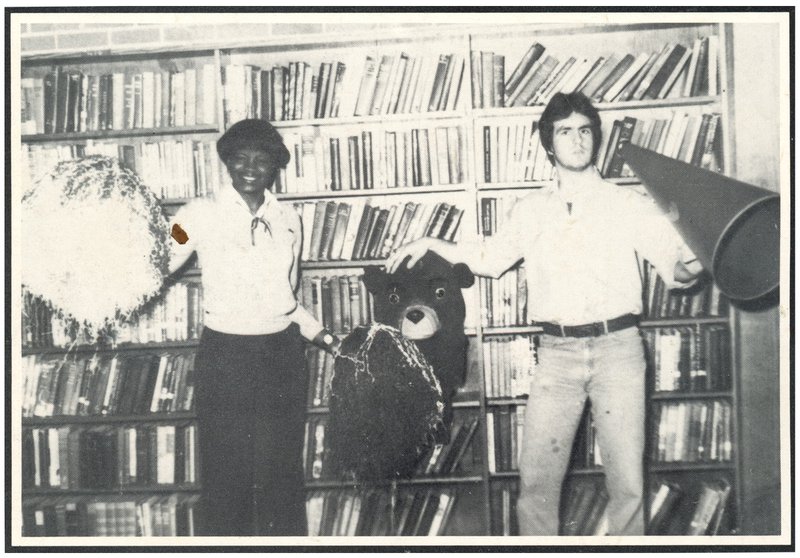

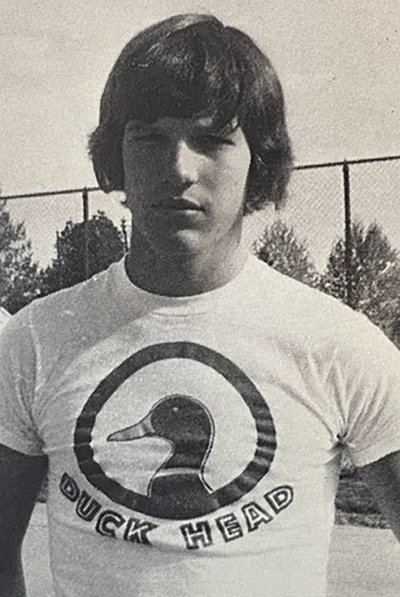

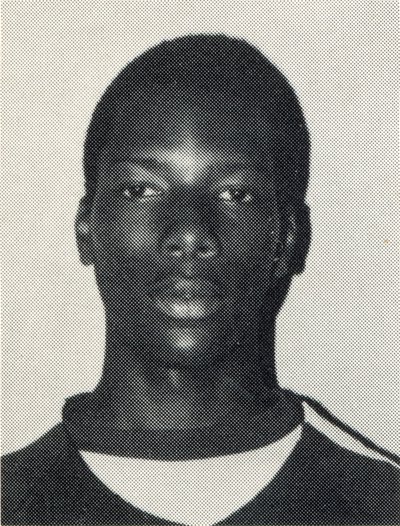

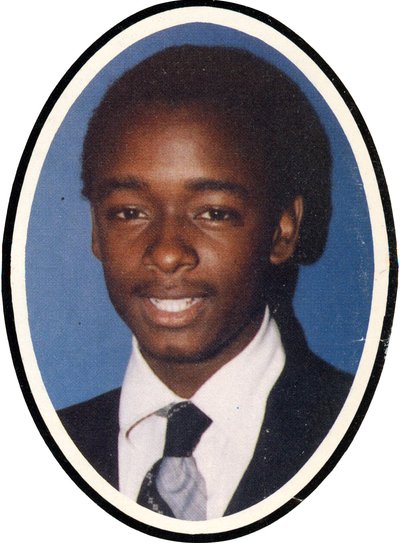

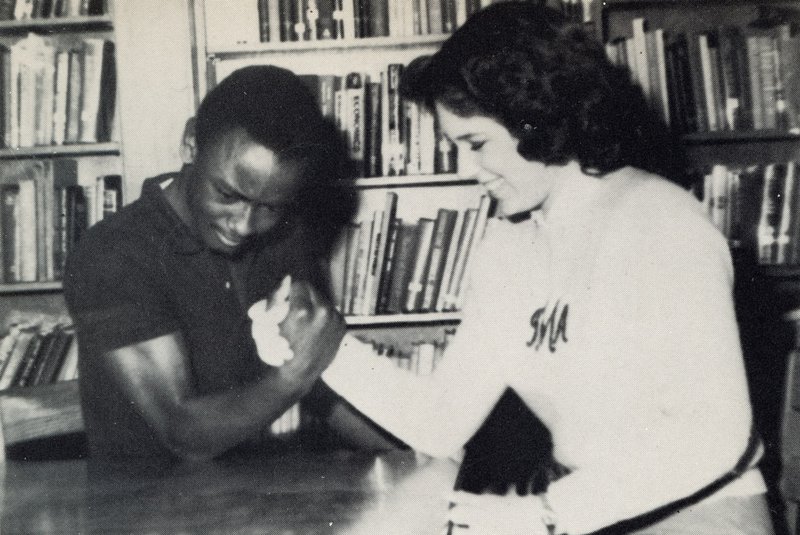

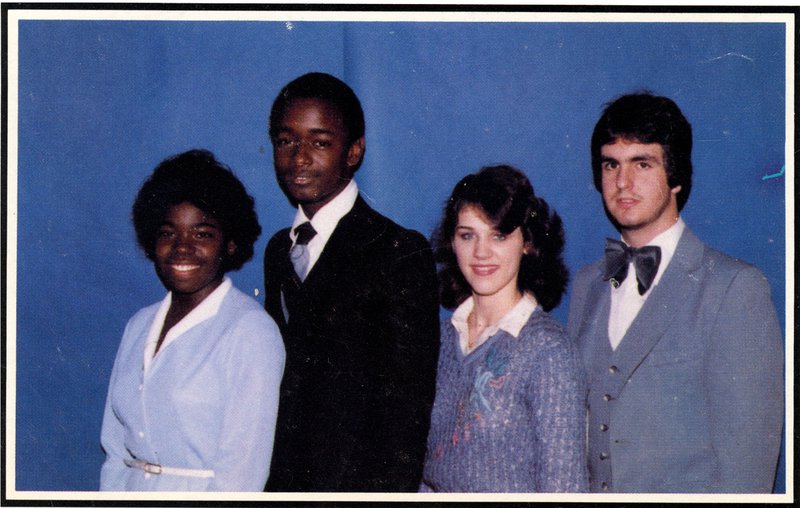

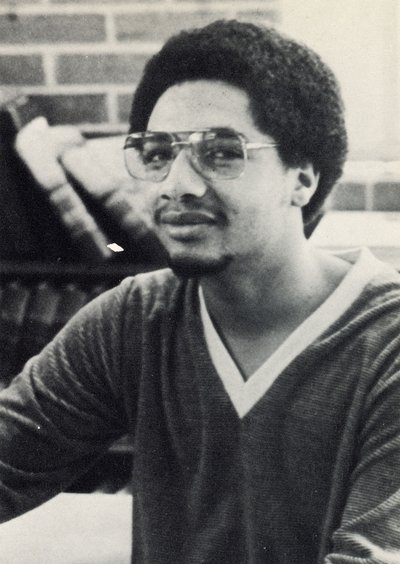

Despite their extraordinary scholastic circumstances, Leland students experienced the same rituals as their peers all across the country—homecoming, school plays, prom—as documented in their school yearbooks. The following is a selection from some of those yearbook images, juxtaposed with Leland High School graduates’ words. Together they form an intimate portrait of these former students’ experiences, while also capturing a particularly American educational story, in all of its complexity.

There were wonderful social relationships between 8:15 and 3:30 and at football games and working on homecoming floats and whatever else. But they didn’t extend beyond that between Black kids and white kids. And it didn’t seem to be because white kids said, “Well I don’t want to do anything with you after school.” Or Black kids, “I don’t want to do anything…” It was just the way it was. School was out and the bell rang and we went home. — Pam Pepper, Leland High ‘82

My best friend was a Black kid my age….We’d hang out together in a school room for hours sometimes. I remember wanting to have him over for my birthday. And I can’t say someone said, “No, you can’t do that,” but it was heavily frowned upon. — John McCandlish, Leland High ‘83

I know that we had separate parks for years and Lions Park we always called it the white folks park, because it was for mainly whites. It was a city park I think, but it was being run by the Lions Club. We had our park over at Breisch High School, so you stay on your side of the track we’ll stay on ours, so to speak. — Billy Barber, Leland High ‘83

What we didn’t really do a lot of is socialize. I might have gone to another white person’s house, but I can count on one hand maybe the number of times because it’s just for whatever reason it was not a thought that that’s something that we did or should do. — Van Poindexter, Leland High ‘82

The children were ready to evolve, and it was a challenge…For the most part, we taught our parents. We taught our parents that we were determined. We taught our parents that we were together. We taught our parents even when they really gritted their teeth about our position of being a community, a true community. And that we were relentless and determined to do that. — Jessie King, Leland High ‘82