Building Boulder City

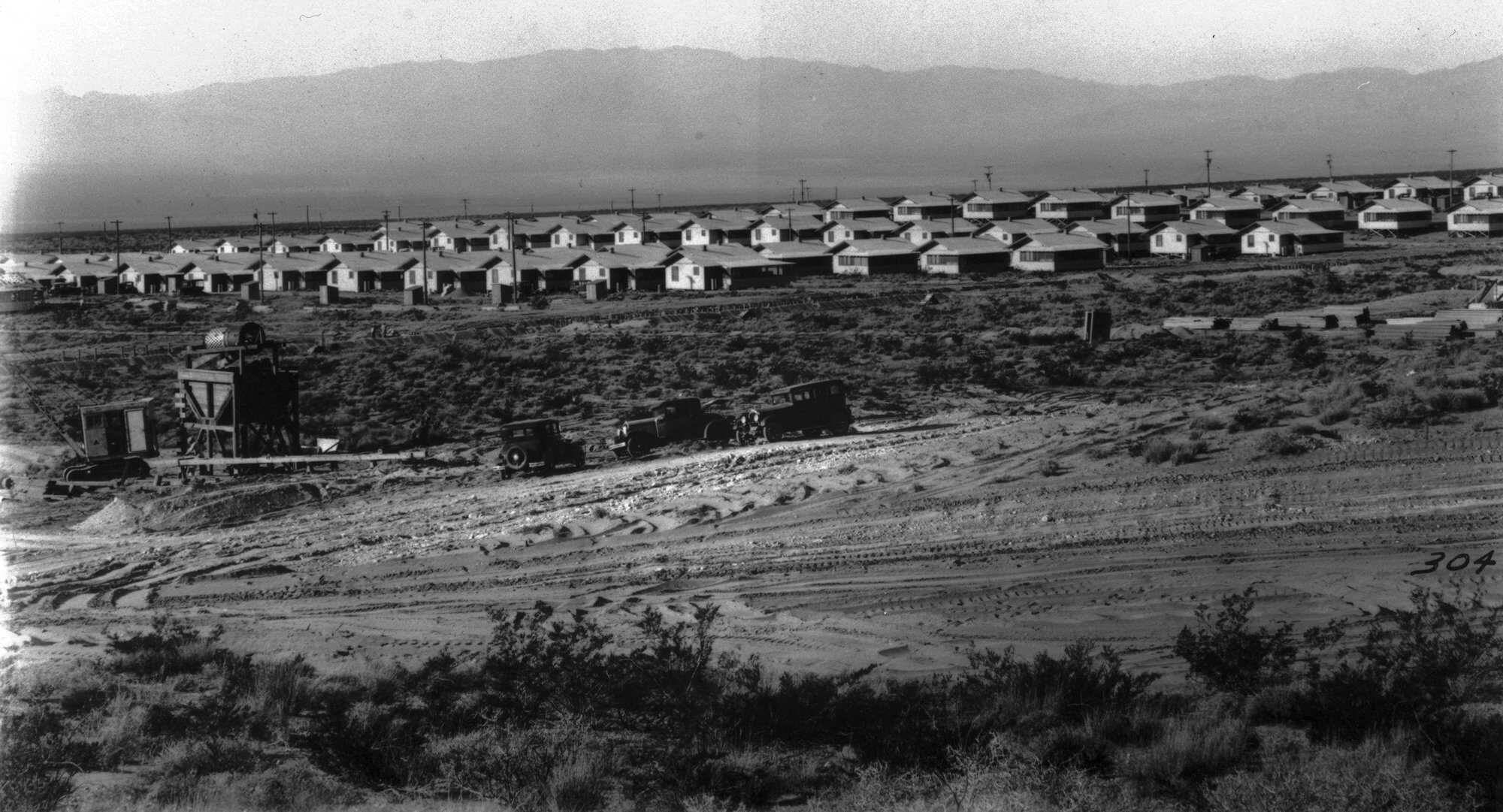

For citizens shaken by the tumultuous effects of the Great Depression, the Hoover Dam project provided two essentials that were in short supply: work and housing. At the project’s start, those who were lucky enough to be hired on as laborers were forced to hunker down, families and all, in a dry and barren spot called Ragtown. Ila Clements-Davey, the daughter of a dam worker, recalls the place: “There was just nothing. There was no facility. Nothing. There was nothing green around here. Everything was baked, hot, and brown.”

By 1932, however, dam workers’ living conditions improved as Boulder City, located on a broad ridge above Hemenway Wash, neared completion. Boulder City was essentially a government reservation, constructed under the jurisdiction of the Reclamation Service. It had large dormitories for single men, and one-, two-, and three-room cottages for families. An enormous mess hall served 6000 meals a day. Every week, 12 tons of fruit and vegetables were shipped in along with five tons of meat and two-and-a-half tons of eggs. For $1.50 a day, a man received three square, all-you-can-eat meals. As the construction project wore on, Boulder City expanded. Its landscape was said to have changed so rapidly that it was common for a man to come home after his shift and walk into the wrong house.

Despite providing the valued comforts of shelter and sustenance, there was no mistaking Boulder City for anything less than a fortified camp. The security gate at its entrance, erected during a period of labor unrest in 1931, was there to remind all who entered that there were rules to be followed. Banned was any hint of the gambling, drinking, or prostitution that flourished down the highway in Las Vegas.

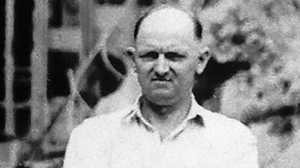

Overseeing the operation of this model town was a 69-year-old former newspaper editor and Justice Department employee named Sims Ely. Ely possessed all legal, moral, and judicial power in Boulder City. He was both known and feared as an “iron-fisted gentleman.” Boulder City resident Mary Ann Merrill remembered Ely as “a hard man.” “I guess he was fair in a lot of ways, but he had his own ideas and he put them into practice. And you had to go by his rules. He thought of it as his town,” Merrill went on to say.

While Boulder City provided plenty of order, it lacked any formal education system or adequate health care. The U.S. government provided no funds to set up schools within the town, and the small amount of money donated by Six Companies was only enough to set up makeshift schoolhouses. Six Companies did underwrite a hospital, which opened in 1932, but it provided care only for dam workers. Their spouses and children were left to fend for themselves. Such exclusion was not unheard of in Boulder City. Despite the emergence of an interdependent civic life, complete with a library and church, Boulder City’s sense of community excluded minorities. African American, Native American, and Hispanic dam workers were not allowed to live within the gates of this makeshift desert oasis.