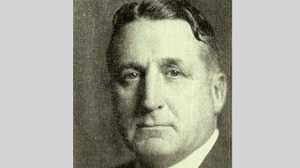

Chief engineer: Frank Crowe

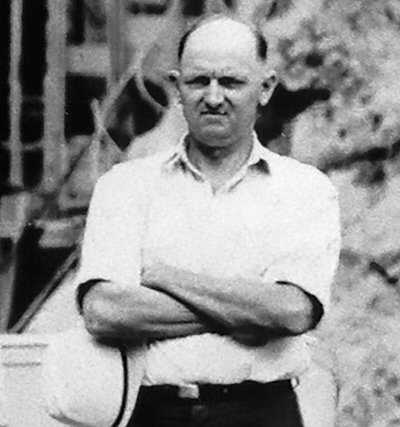

Frank Crowe had a motto: Never my belly to a desk. The testimony of the loyal workers who followed him from construction job to construction job indicated that he was true to his word. Saul “Red” Wixson, a worker on the Hoover Dam project, remembered seeing Crowe roaming the work site at two a.m. “He didn’t want to listen to what was going on down there. He wanted to see it with his own eyes.”

Born in Trenholmville, Quebec in 1882, Crowe lived his early days in New England. While studying civil engineering at the University of Maine, Crowe became intrigued by the romantic image of the American West painted by a guest speaker from the United States Reclamation Service. By the end of the speaker’s presentation, Crowe had signed on for a summer job surveying the drainage basin of Yellowstone River near Glendive, Montana. That summer job marked the beginning of a 20-year career with the Reclamation Service during which Crowe developed a reputation as the government’s best construction man.

He was especially skilled at devising time-saving, efficient construction methods and pioneered the use of numerous pieces of new equipment. In 1911, while working on construction of the Arrowrock Dam in Idaho, Crowe developed two practices that proved pivotal in the building of superdams. The first was a pipe grid used to transport cement pneumatically, the second was an overhead cableway system employed to deliver concrete rapidly to any point on a construction site. By 1924, Crowe was working as general superintendent of construction for the Reclamation Service. He was responsible for construction projects in 17 Western states. Crowe’s enthusiasm for his job was dampened by the government’s decision to use private contractors to build dams. Crowe then made a decision of his own. He quit his government job and signed on with the construction firm of Morrison-Knudsen, which had recently joined forces with Utah Construction to build dams. Freed from his desk job, Crowe would now be in his element. He supervised construction of the Guernsey Dam in Wyoming, the Coombe Dam in California, and the Deadwood Dam in Idaho, among others. Then along came Hoover.

“I was wild to build this dam,” Crowe would later recall. “I had spent my life in the river bottoms, and (Hoover) meant a wonderful climax—the biggest dam ever built by anyone, anywhere.” Author and engineer Donald Wolf describes Crowe as “a commander, a field commander. Everybody knew he was good at this work. Everybody knew he was firm and fair and consistent.”

When the government opened bidding on the Boulder (Hoover) Dam project to private contractors, the newly formed entity called Six Companies put their faith in Frank Crowe to crunch the numbers and come up with the winner. Crowe did not disappoint them. His bid of $48,890,955 was just $24,000 shy of the estimate arrived at by the Reclamation Service’s own engineers. Six Companies was awarded the contract and Frank Crowe prepared to embark on the greatest adventure of his life.

Crowe had been charged with commanding a ragtag army of unemployed men and turning them into the builders of the greatest monument of industrial might of the day. Fighting a brutal climate and an unyielding deadline, Crowe used innovation, motivation, and inspiration to get the job done. Worker Elton Garrett recalled, “Frank Crowe was a genius for organized thinking and for imparting organized thinking to other people… He not only was an engineering genius, he was a people genius. That went a long ways.” It went far enough to ensure that the job was completed two years ahead of schedule.

But in August 1931, workers went out on strike to protest a pay cut and demand better work conditions in compliance with state mining safety laws. Crowe stood firm during the eight day strike with his Six Companies’ bosses, and rejected the workers’ demands. His ultimatum for them to go back to work or leave the project and the reservation split the strikers and eventually broke the strike.

Frank Crowe walked away from his accomplishment at Hoover Dam with a $350,000 bonus. He went on to build four more dams, but Hoover would stand as his crowning achievement.