Madame Muckraker

Ida Tarbell's dogged demand for facts set the standard for investigative reporting.

By Kathleen Brady

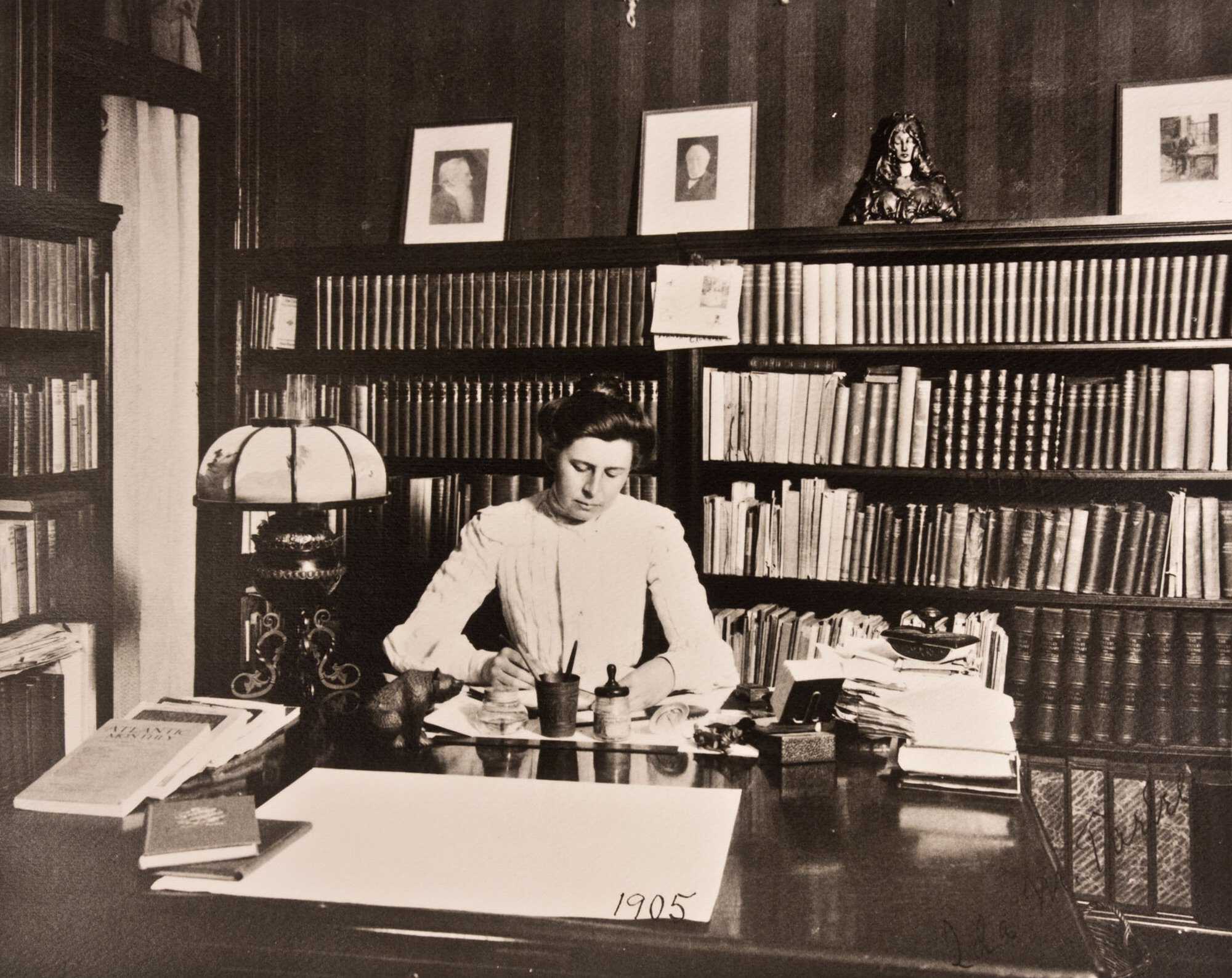

It is worth remembering that the journalist who pioneered investigative reporting at the turn of the 20th century grew up wanting to be a scientist. Born in Western Pennsylvania in 1857, Ida Tarbell was fascinated by geology, by the various kinds of rocks and how they were formed, and by the motion of the planets and the vast expanse of the universe. When Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution cast doubt on the Biblical story of creation, the adolescent studied botanical specimens under her microscope to see if she could prove the existence of God.

Later, she would use the scientific method of gathering and testing evidence in her work as a journalist. Author of The History of the Standard Oil Company, an investigation into the business practices of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Ida Tarbell would become the torchbearer of the intrepid journalists Teddy Roosevelt called “the Muckrakers.” And she did all this at a time when she, as a woman, couldn’t even vote.

After graduation from Allegheny College in 1880, Tarbell took a teaching post, one of few career paths for women. She intended to save money for future scientific study, but she hated teaching and abandoned it. The one opportunity open to her was with The Chautauquan, the magazine of a local but growing religious and educational movement. She discovered that she loved writing, and followed her passion to Paris, where she freelanced for several years.

She was lured home in 1894 to work for the influential editor Sam McClure at his eponymous magazine. Tarbell’s first work for McClure’s was a short series on Napoleon Bonaparte. Unlike the ponderous tomes that had been written about the French emperor, her portrait was written, as she said, “on the gallop,” and it resulted in a fresh, lively story that made him a real person — albeit a world-changing one — that readers were fascinated to meet.

On the heels of that success, McClure assigned Tarbell to write a series of articles on Abraham Lincoln. Earlier biographers had painted a squalid picture of Lincoln’s early life; Tarbell presented him as a man of the frontier, where life was austere but meaningful. Until the close of her life, she would be known as the foremost biographer of Lincoln.

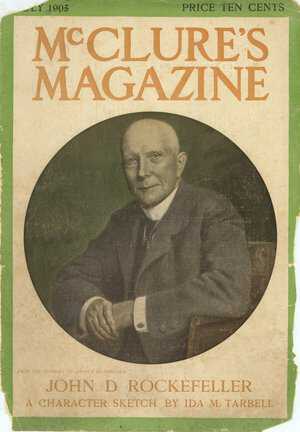

Still, Tarbell’s greatest accomplishment lay ahead of her. The ever-prescient Sam McClure had decided that the next great topic would be the rise of monopolies and the consolidation of American industries in the hands of a few businessmen. He wanted Tarbell to write about one of them: John D. Rockefeller, whose Standard Oil Company controlled 75 percent of the market.

Initially, Tarbell didn’t think there was much of a story there. She had grown up in Titusville, Pennsylvania, the center of U.S. oil production, and was so familiar with the petroleum industry that she thought its story would bore readers. Moreover, she believed research would reveal that Rockefeller had triumphed because he was better organized and more focused than the competitors he had driven from the business. Reluctantly, she agreed to write the series.

But Rockefeller’s ascension proved to be far from straightforward. Tarbell learned that the key to the story was an elusive 126-page book called The Rise and Fall of the South Improvement Oil Company. Printed by the Petroleum Producers Union in 1872, it contained congressional testimony stating that railroads colluded to give the South Improvement Company — their biggest and most powerful customer — illegal kickbacks. It also revealed that the railroads had agreed to provide South Improvement with inside information about competitors. These arrangements violated legal requirements that each railroad be a “common carrier” and treat all customers equally.

Though he always claimed that he had nothing to do with it, South Improvement was a Rockefeller corporation. It was, in fact, an early incarnation of Standard Oil. And this 30-year-old book, Tarbell believed, proved it.

But where was it? People in the oil regions told her that material damning to the magnate had been purchased and destroyed either by the Standard Oil Company or by railroad presidents who worked with the firm. Tarbell scoured offices, attics, and libraries across the oil regions, but was unable to find a copy. Finally, in desperation, and as something of a joke, she requested it at New York Public Library. To her shock, a librarian immediately produced the volume. She had her smoking gun.

Readers were riveted by the series Tarbell thought no one would read. They remembered a time not long past when industries had been controlled by many competing firms. Her story explained how the oil industry came to be dominated by one person, and how a monopoly could take control of public resources and marshall them for its own benefit. McClure expanded her assignment from three installments to six, and then to twelve.

Hungry for facts, Tarbell collected as much evidence as she could. She interviewed a host of people affected by Rockefeller in the U.S. and Europe. But even as the facts piled up, Tarbell had to acknowledge the genius of the oil baron. Although she disliked his business methods, she developed a respect for his drive, energy, and organizational skills. She wrote that his achievements would have been equally great had he followed the letter of the law.

After her series finally concluded in November of 1904, the work was published in two volumes, complete with 64 appendices of documentation, filling 241 pages. In 1906, the U.S. government, drawing on information she had uncovered in several states, brought suit against Rockefeller’s company under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. In 1911, the Supreme Court found that the Standard Oil Company constituted a monopoly and had restrained trade unduly. It ordered the company to divest itself of its major holdings — 33 companies in all.

In the end, Rockefeller’s reputation was damaged, but his power and fortune emerged unscathed. Standard Oil was broken up, but separately, the various firms generated even more money for Rockefeller than the trust had done. Still, Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States forced the Court to define and reinforce an area of previously vague law — which would become a powerful tool in later antitrust cases.

The rest of Tarbell’s professional life would be marked by a determination to show that sound business practices could benefit society and that success was not entirely a matter of greed and rapaciousness. After World War I, she published a series that criticized high protective tariffs, and she served on Woodrow Wilson’s Industrial Conference and Warren G. Harding’s Conference on Unemployment. She profiled the Italy of the 1920s for McCall’s Magazine and — always even-handed — found Mussolini himself to be impressive, even as she decried his totalitarianism. She died in 1944 at the age of eight-six.

Tarbell had hoped to see Rockefeller put out of business; when he was not, she doubted that she had accomplished very much through her historic exposé. But with her scientific, evidence-based approach, she set the standard for investigative journalism. The woman who had challenged the trust would become an inspiration for future generations of journalists looking to "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."

Kathleen Brady is the author of Lucille, The Life of Lucille Ball, and Ida Tarbell: Portrait of a Muckraker, for which she was named a Fellow of the Society of American Historians. She is a past co-director of the Biography Seminar at New York University and a former reporter for Time Magazine.

Published November 2017.