Scientific Investigation of the 1918 Flu

Despite recent advances in microbiology, early 20th-century scientists struggled to understand the source of the deadly 1918 influenza epidemic and how best to prevent it. Some thought it might develop from a germ planted by Germans trying to get an edge in World War I. Others tried to protect themselves from the flu by drinking noxious homemade elixirs. It was not until the late 1990s that researchers armed with the latest technology and a greater understanding of molecular biology were able to uncover some of the hidden mysteries surrounding the strain of influenza virus that triggered such a devastating epidemic in 1918.

In 1997, the Molecular Pathology Division of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) identified genetic material from the 1918 influenza in the frozen remains of a Native Alaskan victim of the disease, buried for nearly 80 years in Brevig Mission, Alaska. AFIP scientists identified two more positive cases in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples from the AFIP archives. Both archival cases were autopsies of U.S. servicemen who died during the pandemic — the first in Fort Jackson, SC, the second in Camp Upton, NY. While all of the virus’ genetic material – the RNA – was fragmented into tiny pieces, the scientists were able to use the latest molecular techniques to identify complete gene structures of the virus.

In 1999, the AFIP reported that after completely analyzing a critical gene from the 1918 influenza virus their researchers had determined that the 1918 virus apparently evolved in mammals, either humans or pigs, over a period of years before it matured into a virus strong enough to kill millions. Ann Reid, a molecular biologist with the AFIP and the main author of the study, told the Associated Press that the gene probably “was adapting in humans or in swine for maybe several years before it broke out as a pandemic virus.” Reid added, “We can’t tell whether it went from pigs into humans or from humans into pigs.” Through this investigation, Reid was able to map a gene called the hemagglutinin, which is key to allowing the influenza virus to take hold. Reid reported that the hemagglutinin closely resembles mammal genes.

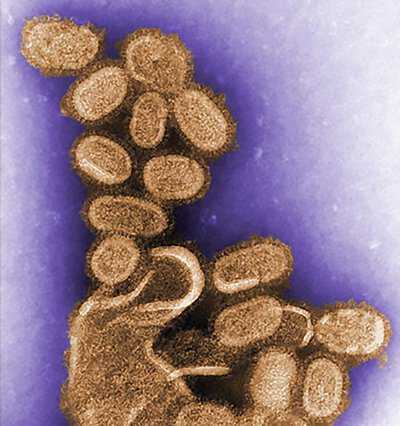

In 2005, researchers from the CDC, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and the U.S. Department of Agriculture successfully collaborated in sequencing and reconstructing the 1918 influenza virus. According to their research findings, the virus not only proved deadly to mammalian specimens, but also proved virulent against chicken embryos. The team, including Ann Reid and Jeffery Taubenberger, concluded that polymerase genes found in the 1918 reconstructed flu are more similar to those found in avian flu viruses than those found in other mammalian flu viruses. These findings have swung the scientific community pendulum back to attributing the 1918 influenza virus to an avian source rather than that of a swine. Since the publications of these findings, other members of the scientific community have debated and disputed these conclusions. It seems that despite advances in science and technology, many of the puzzles of the 1918 influenza virus may forever be clouded in mystery.