Influenza Across America in 1918

March 11

At Fort Riley, Kansas, an Army private reports to the camp hospital just before breakfast complaining of fever, sore throat, and headache. He is quickly followed by another soldier with similar complaints. By noon, the camp’s hospital has dealt with over 100 ill soldiers. By week’s end, that number will jump to 500.

July 22

Public health officials in Philadelphia issue a bulletin about the so-called Spanish influenza.

August 27

Sailors stationed onboard the Receiving Ship at Commonwealth Pier in Boston begin reporting to sick-bay with the usual symptoms of the grippe. By August 30, over 60 sailors were sick.

Soon, Commonwealth Pier was overwhelmed and 50 cases had to be transferred to Chelsea Naval Hospital. Flu sufferers commonly described feeling like they “had been beaten all over with a club.”

Early September

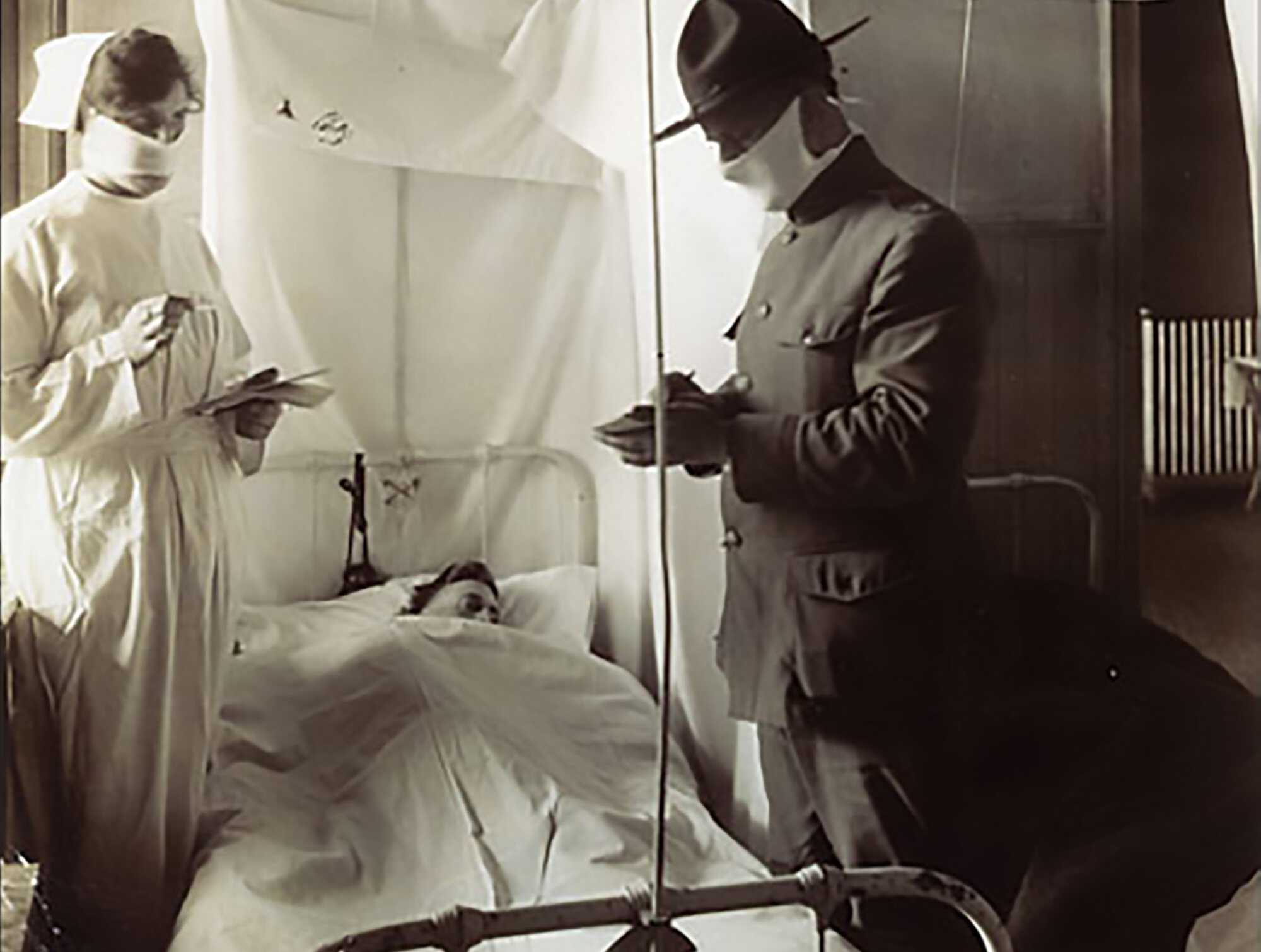

Dr. Victor Vaughan acting Surgeon General of the Army, receives urgent orders to proceed to Camp Devens near Boston. Once there, what Vaughan sees changes his life forever:

“I saw hundreds of young stalwart men in uniform coming into the wards of the hospital. Every bed was full, yet others crowded in. The faces wore a bluish cast; a cough brought up the blood-stained sputum. In the morning, the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cordwood.”

On the day that Vaughan arrived at Camp Devens, 63 men died from influenza.

The Navy Radio School at Harvard University in Cambridge reports the first cases of influenza among the group of 5,000 young men studying radio communications.

September 5

The Massachusetts Department of Health alerts area newspapers that an epidemic is underway. Dr. John S. Hitchcock of the state health department warns that “unless precautions are taken, the disease in all probability will spread to the civilian population of the city.”

September 13

US Surgeon General Rupert Blue of the United States Public Health Service dispatches advice to the press on how to recognize the influenza symptoms. Blue prescribed bed rest, good food, salts of quinine, and aspirin for the sick.

Royal Copeland, the Health Commissioner of New York City, announces, “The city is in no danger of an epidemic. No need for our people to worry.”

September 18

Lt. Col. Philip Doane, head of the Health and Sanitation Section of the Emergency Fleet Corporation, speaking in Washington, D.C., fuels the rumor and speculation by blaming the Germans for the deadly influenza that was striking Americans. Said Doane: “It would be quite easy for one of these German agents to turn loose Spanish influenza germs in a theater or some other place where large numbers of persons are assembled. The Germans have started epidemics in Europe, and there is no reason why they should be particularly gentle with America.”

September 24

Edward Wagner, a Chicagoan newly settled in San Francisco, falls ill with influenza.

San Francisco public health officials had been downplaying the potential dangers posed by the flu. Dr. William Hassler, Chief of San Francisco’s Board of Health had gone so far as to predict that the flu would not even reach the city.

September 28

200,000 gather for a 4th Liberty Loan Drive in Philadelphia. Days after the parade, 635 new cases of influenza were reported. Within days, the city will be forced to admit that epidemic conditions exist. Churches, schools, and theaters are ordered closed, along with all other places of “public amusement.”

Congress approves a special $1 million fund to enable the U.S. Public Health Service to recruit physicians and nurses to deal with the growing epidemic. US Surgeon General Rupert Blue set out to hire over 1,000 doctors and 700 nurses with the new funds. The war effort, however, made Blue’s task difficult. With many medical professionals already engaged in lending care to fighting soldiers, Blue was forced to look for some recruits in places like old-age homes and rehabilitation centers.

October 2

Boston registers 202 deaths from influenza. Shortly thereafter, the city canceled its Liberty Bond parades and sporting events. Churches were closed and the stock market was put on half-days.

October 6

Philadelphia posts what will be just the first of several gruesome records for the month: 289 influenza-related deaths in a single day.

October 19

Dr. C.Y. White announces in Philadelphia that he has developed a vaccine to prevent influenza. Over 10,000 complete series of inoculations were delivered to the Philadelphia Board of Health. Whether or not the so-called vaccine played much of a role in loosening the flu’s grip on the city became a matter of great debate.

October 22

869 New Yorkers die of influenza or the resulting pneumonia in a single day. In Philadelphia, the city’s death rate for one single week is 700 times higher than normal.

October 31

The crime rate in Chicago drops by 43 percent. Authorities attributed the drop to the toll that influenza was taking on the city’s potential lawbreakers.

The month turns out to be the deadliest month in the nation’s history as 195,000 Americans fall victim to influenza.

November 11

Celebrating the end of World War I, 30,000 San Franciscans take to the streets to celebrate. There is much dancing and singing. Many people wear face masks.

November 20

In only five days, influenza leaves 72 of the 80 native Inupiat inhabitants dead in the small town of Brevig Mission, Alaska. Local survivors bury the victims in a mass grave.

November 21

Sirens wail, signaling to San Franciscans that it is safe — and legal — to remove their protective face masks. At that point, 2,122 are dead due to influenza

December 4

The U.S. public health service publishes an estimate that 300,000 to 350,000 civilian deaths can be attributed to influenza and pneumonia since September 15. The War Department records indicate that another 20,000 deaths have occurred among soldiers.

December 17

The chief clerk of the Navajo Indian reservation reports that influenza has taken the lives of more than 2,000 Navajos in Apache County, New Mexico.

December 27

Boston reports 454 new cases of influenza in a single day.

The epidemic will continue its lethal campaign into 1919, ultimately killing upwards of 600,000 people. It will be deemed the worst epidemic in American history.