The surprise pandemic of 1918 shook Americans’ confidence in the medical establishment that had previously found vaccines for other lethal diseases like smallpox and typhoid. People tried everything to avoid getting the virus — from gargling with mouthwash to wearing masks — but it was not until years after the pandemic was over that scientists made any real breakthroughs.

-

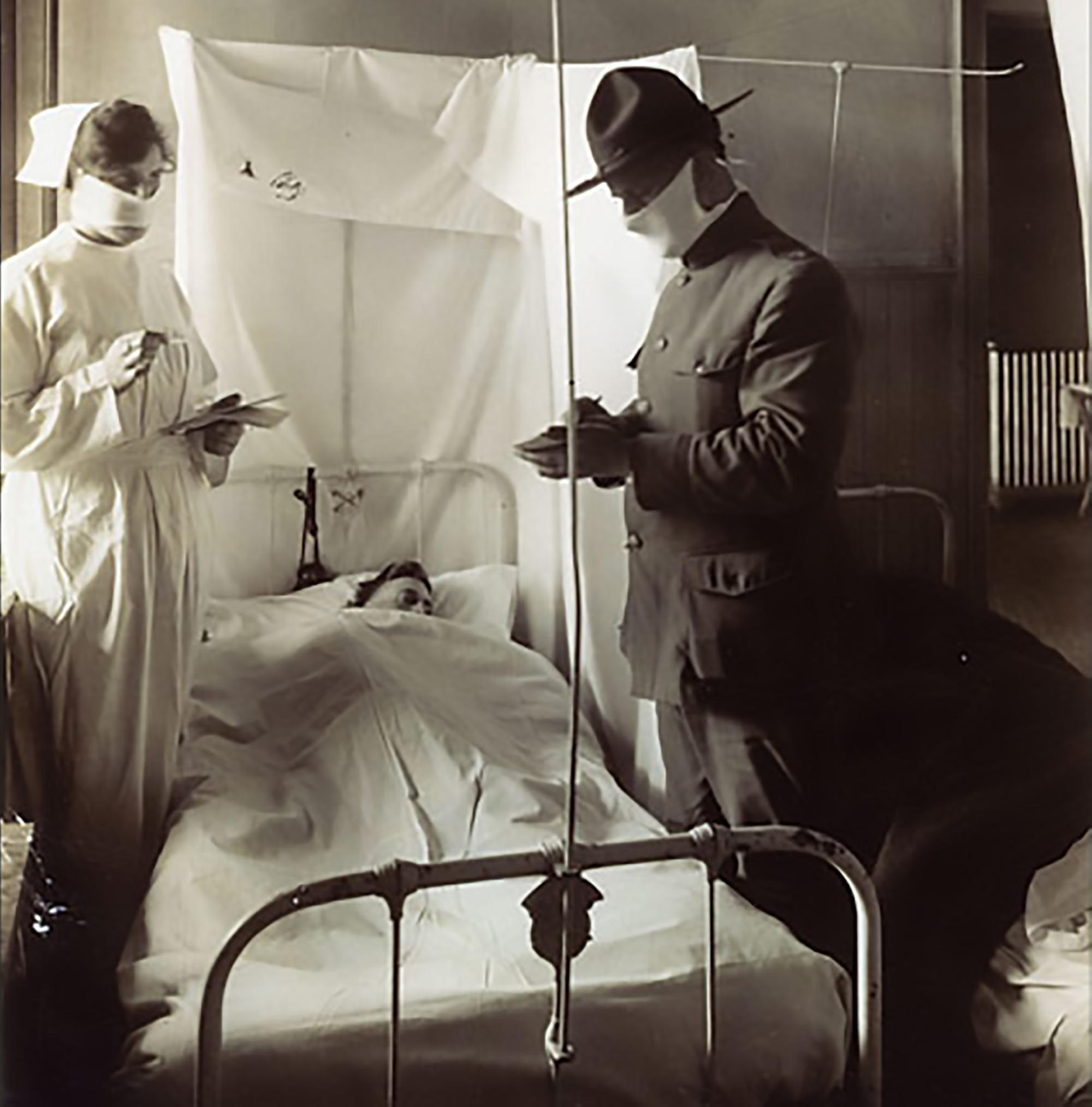

When young, healthy soldiers began getting sick by the dozens in March, 1918, military physicians were baffled by what might be causing it.

Credit: NARA -

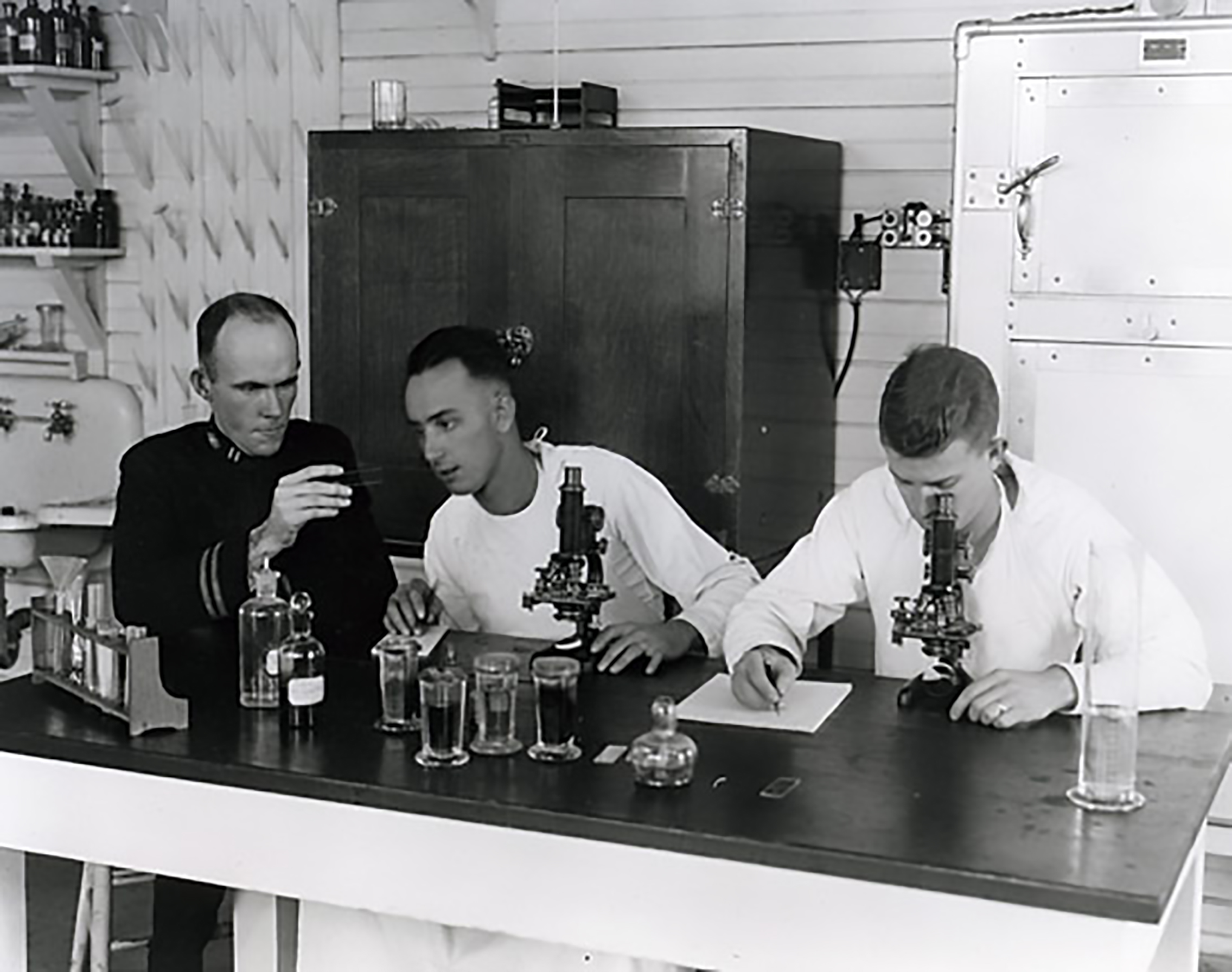

The source of the illness remained a mystery to scientists as viruses were too small and obscure for the optical microscopes available in 1918.

Credit: Naval Historical Center -

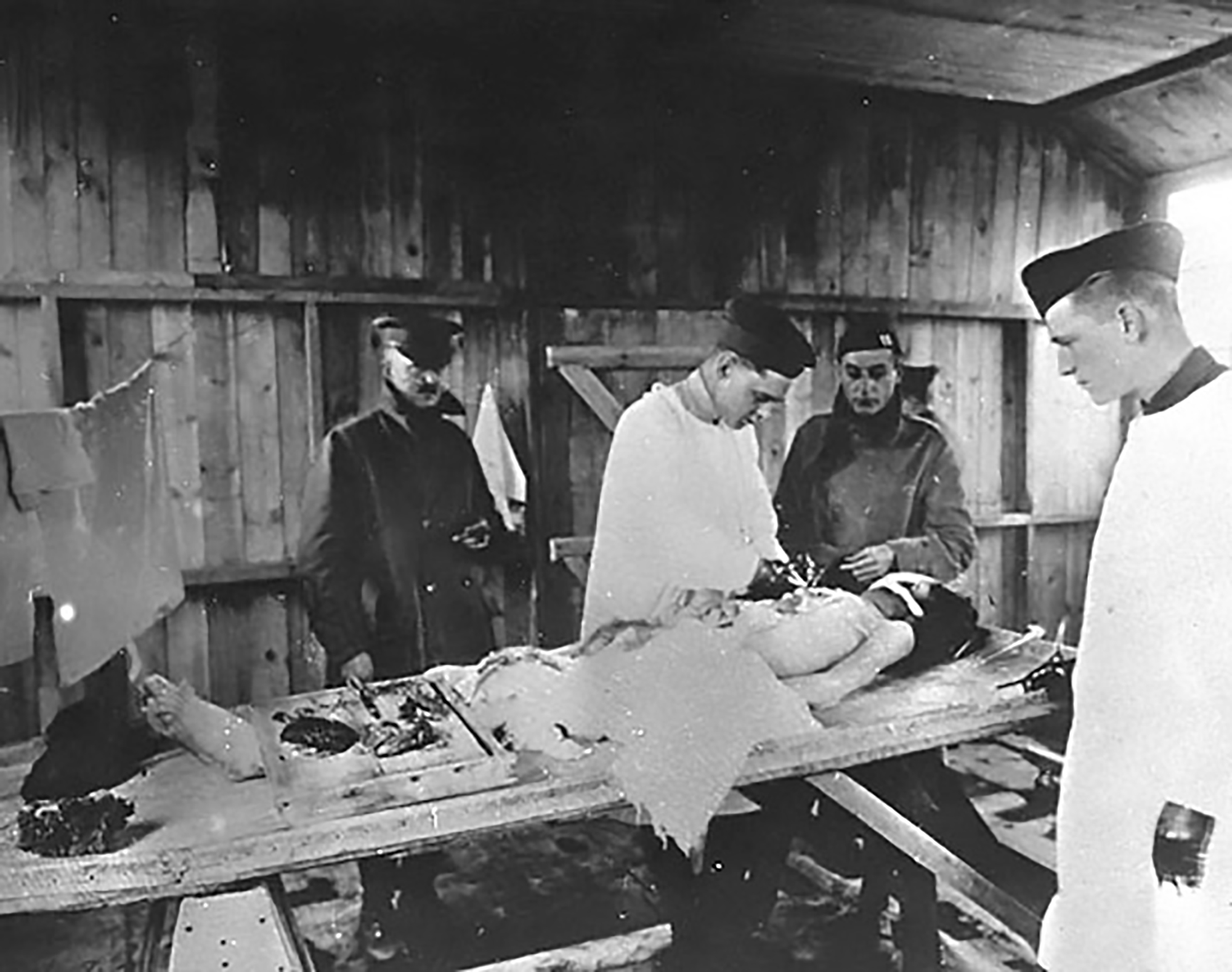

Doctors perform an autopsy at Kerhuon Base hospital in Brest, France. Medical staff here treated more than 3,000 soldiers suffering from influenza-pneumonia, of whom 569 died. Autopsies revealed that influenza victims’ lungs appeared strangely blue and were filled with fluid.

Credit: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources -

In September, Victor Vaughan, Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, made the startling conclusion that the 1918 Influenza was most likely to kill “young, vigorous, robust adults” rather than the elderly or children.

Credit: National Library of Medicine -

Soldiers gargle outside of wooden barracks as a preventative health measure.

Credit: NARA -

A police officer turns away an unmasked man from riding the trolley in Seattle, WA. Health officials believed masks would slow progression of the epidemic.

Credit: NARA -

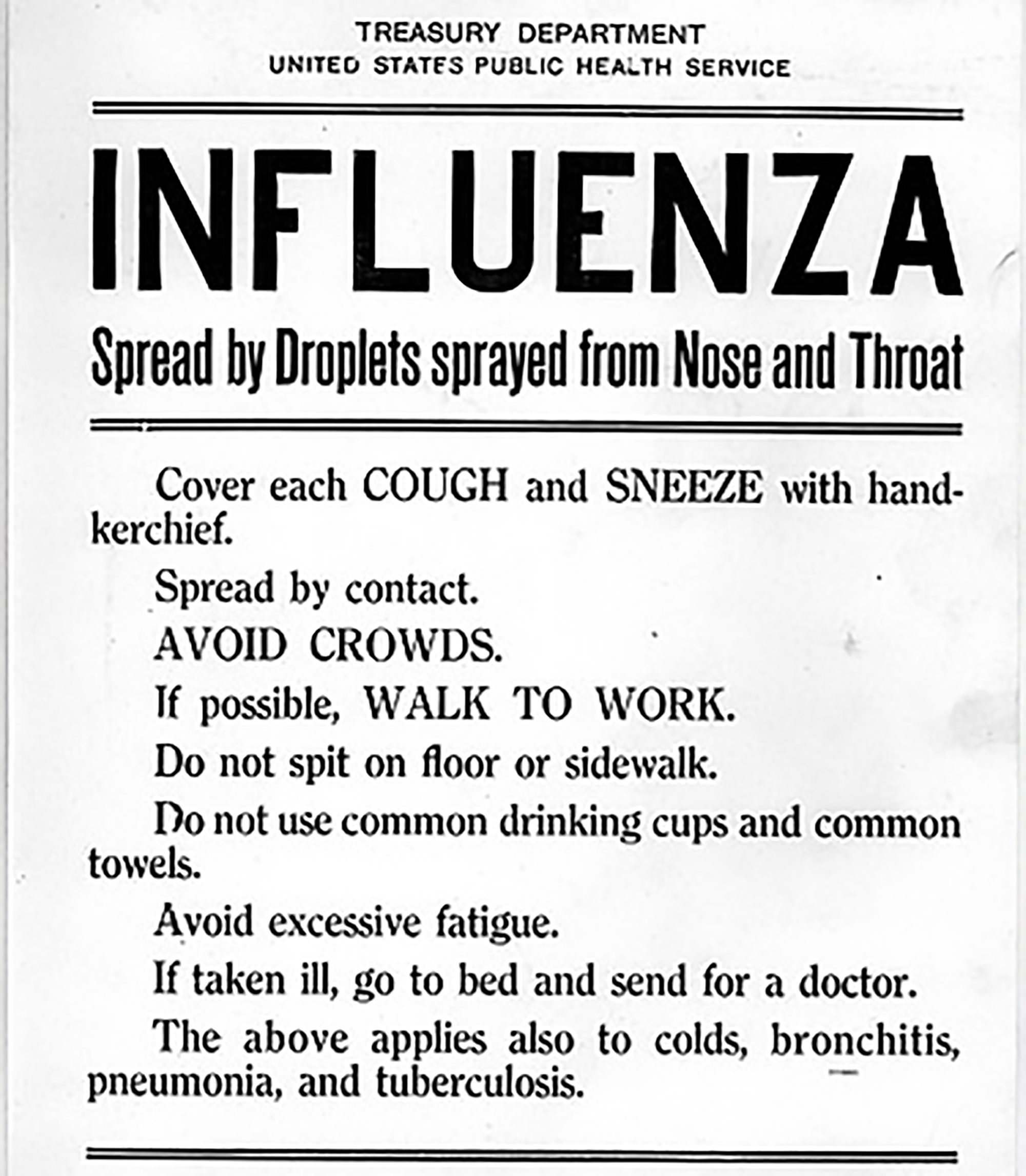

The United States Public Health Service issued this pamphlet in October of 1918 as part of a public education campaign to slow the progress of the disease.

Credit: Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division -

Vaccines like the one being developed here had proven effective against other diseases such as Typhoid, allowing all American soldiers to be inoculated in 1911. But in 1918, while doctors and laymen alike tried nearly everything in search of both a vaccine and a cure for the flu, nothing was successful.

Credit: NARA -

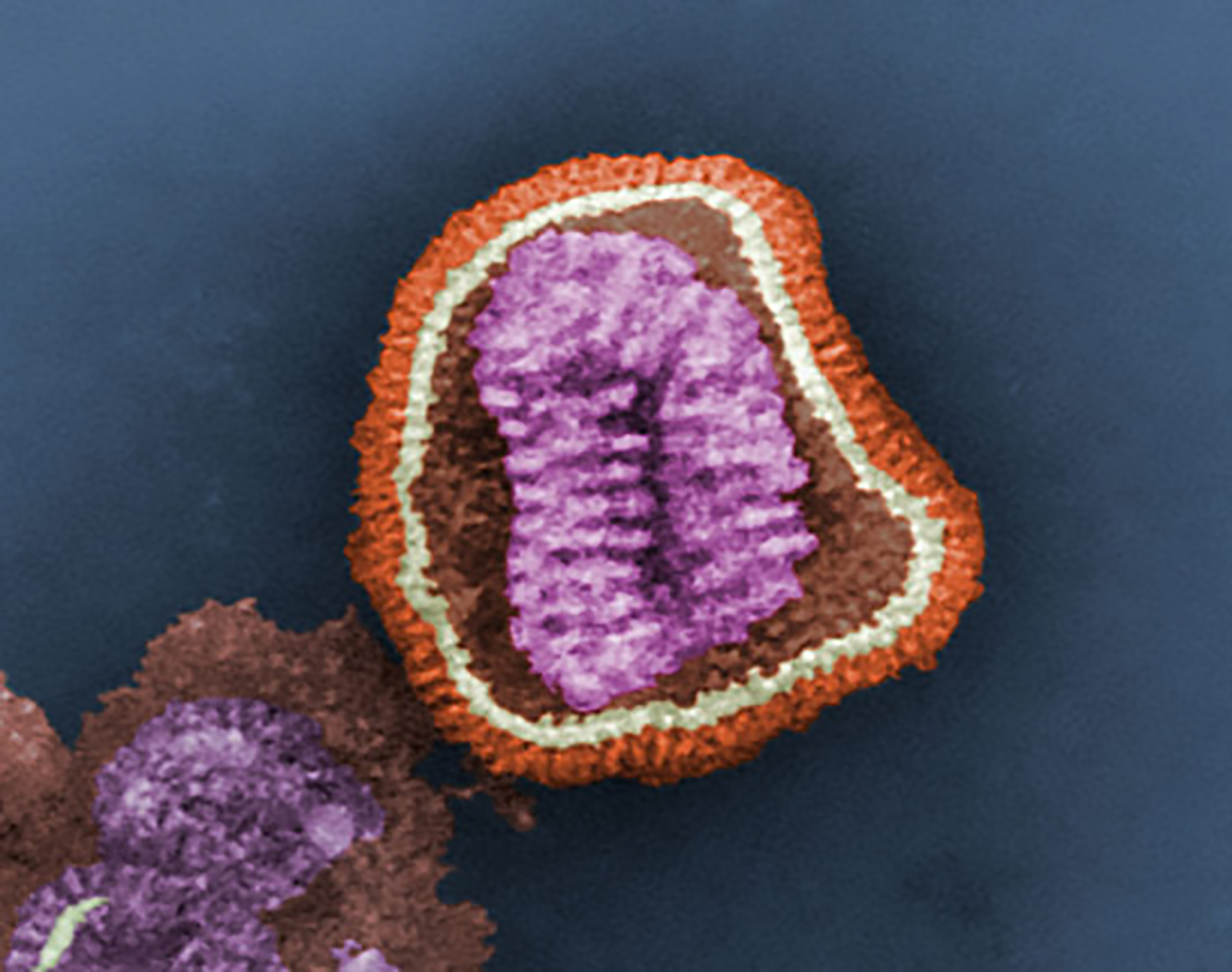

In 1933, the electron microscope allowed new levels of detail to be visible from an influenza virus particle, or “virion.” This advancement helped scientists develop the first successful flu vaccine within a decade.

Credit: CDC / Erskine L. Palmer, Ph.D., M. L. Martin -

In 1976 a jet injector was used to administer influenza vaccine to this patient as part of the U.S. government’s 'swine flu’ vaccination campaign. The government spent more than $100 million in the most expensive and concentrated nationwide vaccination program against influenza to that date.

Credit: CDC / Robert E Bates -

Using tissue samples recovered from two victims, Dr. Terrence Tumpey of the CDC successfully reconstructed the 1918 influenza virus in 2005 in order to identify its deadly characteristics.

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention -

An electron microscope image of the CDC’s recreated 1918 Influenza virus, seen here, 18 hours after infection.

Credit: CDC/Dr. Terrence Tumpey -

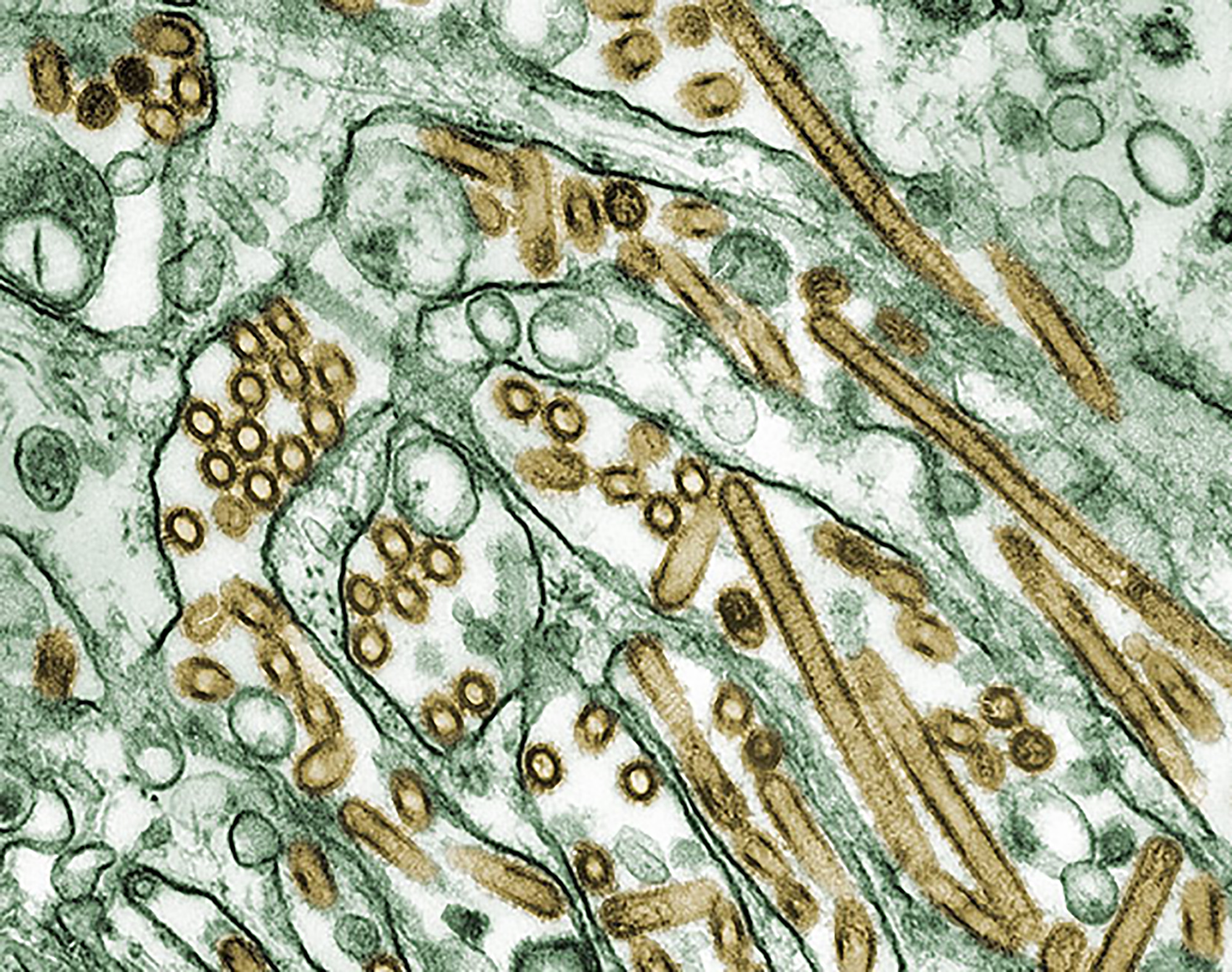

In 2004, scientists and health officials tracked a deadly new strain of influenza known as H5N1. Dubbed Avian or “Bird Flu,” H5N1 viruses appear in gold in this image.

Credit: CDC/Courtesy of Cynthia Goldsmith, Jacqueline Katz, Sherif R. Zaki -

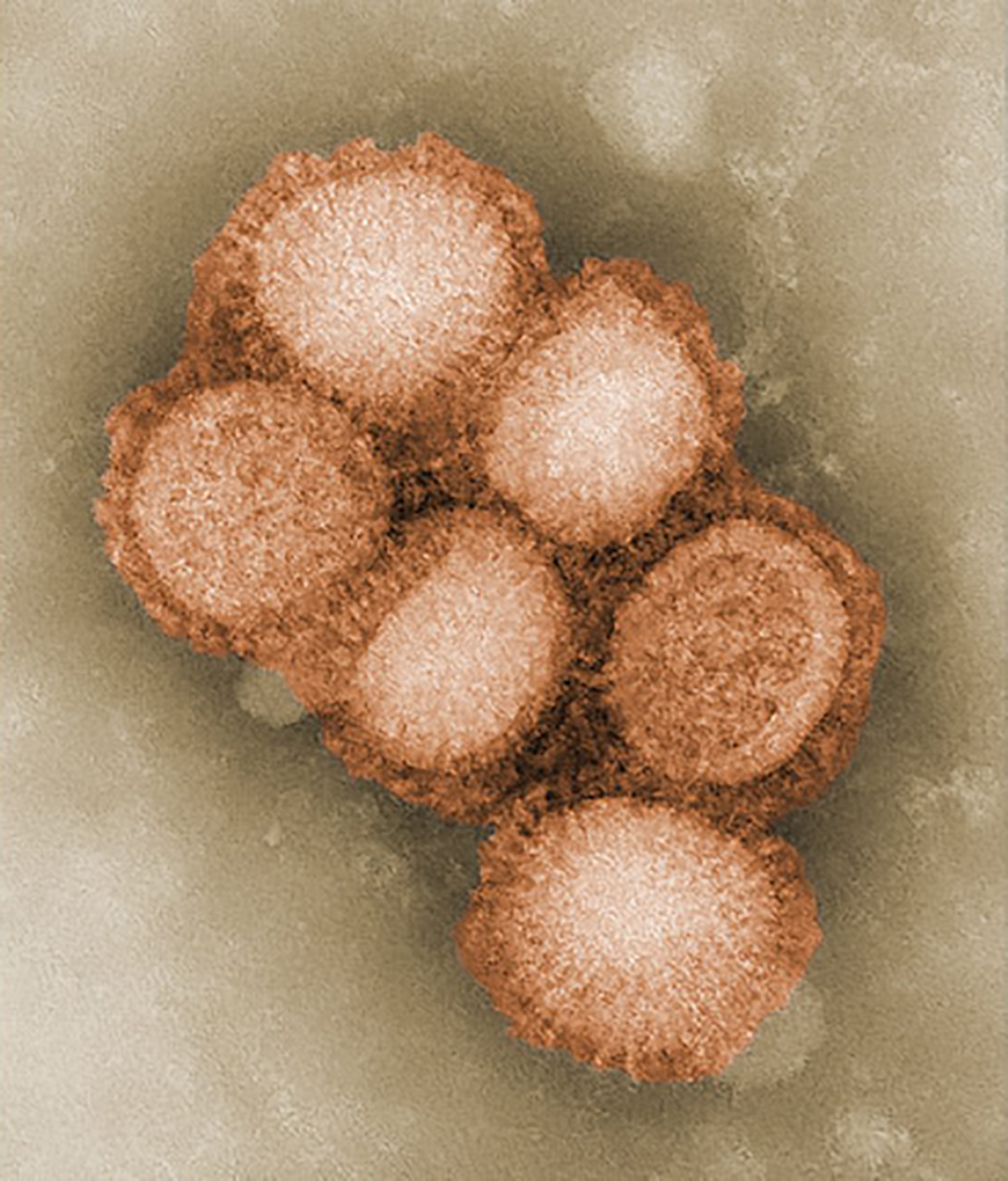

A deadly strain of influenza – H1N1 – emerged in 2009, killing thousands of people worldwide.

Credit: CDC/C.S. Goldsmith, A. Balish