First the Iran Hostage Crisis Happened—then Fame Followed

As one of the hostages' wives, Barbara Rosen was thrust into the biggest media event of its era

Barbara and Barry Rosen met on the tarmac. In 1971, both attended a publicity party for the first 747 airplane at New York’s Kennedy Airport, an event held inside one of the new jumbo jets. Given his naturally more extroverted personality, Barry had the first word. “As I walked through the plane,” Barbara told American Experience, “he approached me and said, ‘Is that an Iranian blouse you're wearing?’ The blouse was actually an Indian blouse, but that sort of set the stage for what our whole life was going to revolve around—that being Iran.”

During two years’ service as a Peace Corps officer there, Barry had fallen in love with Iranian culture; when he had the opportunity to return in 1978, this time as press attaché to the United States embassy in Tehran, he hoped to bring Barbara and their young children—two-year-old son Alexander and newborn daughter Ariana—to experience the country together as a family. As it turned out, Barbara and the kids would never make it.

Iran was in the throes of a populist revolution that in January 1979 unseated the country’s autocratic leader, Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi. Iranians’ hatred of the Shah was nearly matched by their enmity toward the U.S. government, which in 1953 contrived a coup that put the Shah in a position of absolute power. Over the next quarter century, the United States then supported the Shah’s modernization efforts while also enabling his increasingly despotic regime.

This history made U.S. diplomatic personnel prime targets, and by early 1979, the U.S. State Department recalled the majority of its embassy staff in Iran. Those few that remained grew accustomed to regular anti-Shah and anti-American protests outside the embassy compound. “It was frightening,” said Barbara. “And yet, Barry would call and be very nonchalant about it. So it was almost like an adventure. And there was nothing that could prepare us for what actually did happen on November 4th.”

She was up early that Sunday morning, playing with the children in bed, when the phone rang at her parents’ house. (Both Barbara and Barry were Brooklyn natives, and she was living in her childhood home there for support while he was away.) Barbara’s mother called up to the room she shared with Alexander and Ariana. “Come down. Your mother-in-law is on the phone. Something’s happened at the embassy.”

Six hours earlier, a group of young Iranians, mostly Muslim university students, had initiated a takeover of the American diplomatic compound. The students had set their sights on the embassy following a decision by President Jimmy Carter in October: Against his own judgment, but persuaded by his cabinet, Carter had granted the deposed Shah admission to the United States to receive medical treatment for cancer. Many Iranians saw Carter’s decision as evidence of American intent to undermine the revolution that had ousted the Shah, and immediately sought to send the U.S. a message to stay out of Iranian affairs.

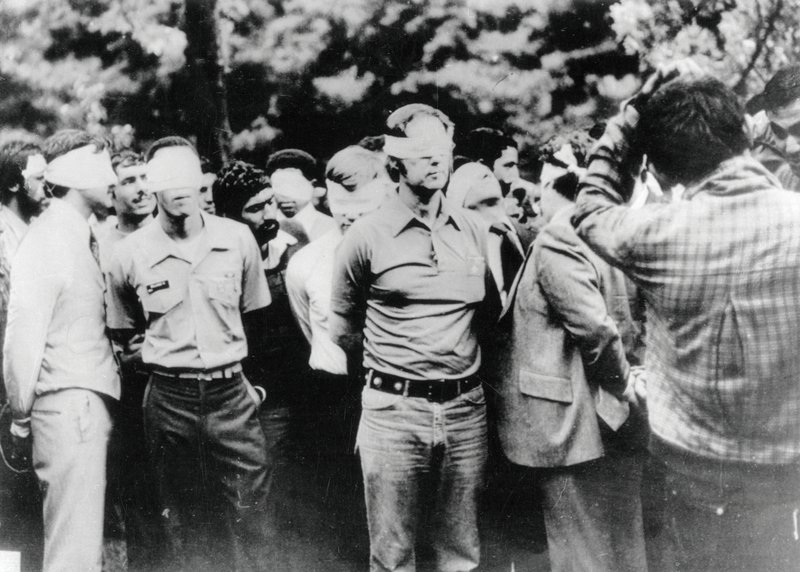

The student militants took 63 Americans hostage, Barry among them. And as radically as Barry’s life changed on that day, so too did Barbara’s.

Though she was by nature an introverted, private person, the hostage crisis now thrust Barbara into an extraordinarily public role. Barry’s capture was at the center of the first foreign policy crisis to take place with live, on-the-ground reporting broadcast in real-time, via satellite. Television audiences were fascinated by the political drama playing out on their screens at home; nightly news broadcasts showed frenzied crowds outside the embassy burning the U.S. flag and Carter in effigy while chanting “Marg bar Amrika!”—“Death to America!” Barbara became a highly sought-after guest on news programs, despite feeling enormously conflicted over her participation in the media frenzy.

In many respects, the attention felt intrusive. Once reporters learned where she lived in Gravesend, Brooklyn, the media held regular vigils outside her parents’ pink clapboard house. On one occasion in January 1980, reporting crews arrived to film outside the property. Disgusted, Barbara drew the shades on the large picture window that looked out onto the maple tree under which she and Barry were married.

On other occasions, however, she readily engaged, hoping to have a positive influence on events as they unfolded. “Television helped in certain ways,” she said in a memoir published several years later, “which is why I kept appearing. It was the best medium for expressing an opinion to a large audience. It also brought Barry from a faceless hostage to an individual people felt they knew, therefore were more concerned about.”

However, she agonized over how her newfound platform might affect her husband and his colleagues. “I don't know if what I'm saying is going to hurt Barry, if I'm going to give something away that I shouldn't be saying,” she told American Experience. “I've never done this before. I was a public school teacher. I'm a mother. I'm a wife. I'm not a media personality.” During one interview with NBC, she described the student militants as “terrorists” and immediately panicked, thinking, “oh my God, what did I just say. Can I take that back?”

Barbara also found herself in another unexpected role, that of meeting with heads of state. About a month into the hostage-taking, when the State Department organized a briefing for the hostages’ family members, she met President Carter. Barbara presented him with photos of Alexander and Ariana, saying, “Just remember that their father is one of the people in the embassy. Keep that in mind, whatever it is that you decide to do.” To garner international support, she also met with French President Giscard d’Estaing and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, and together with several other hostages’ wives, she had a brief audience with the Pope.

As the crisis evolved, Barbara found herself increasingly disillusioned with what she perceived as the widespread commercialization and lack of substantive reporting of the news. At one point she was tipped off by a producer that a news program was about to air footage—for which they had paid the hostage-takers—from inside the U.S. embassy compound.

Horrified, she watched her gaunt husband onscreen, being held captive 6,000 miles away. Minutes later, the network contact called her back to ask if she wanted to join him in the studio. “He suggested a film of me watching and reacting to the devastating sight of Barry,” she recalled, “which, he said, would be very effective.”

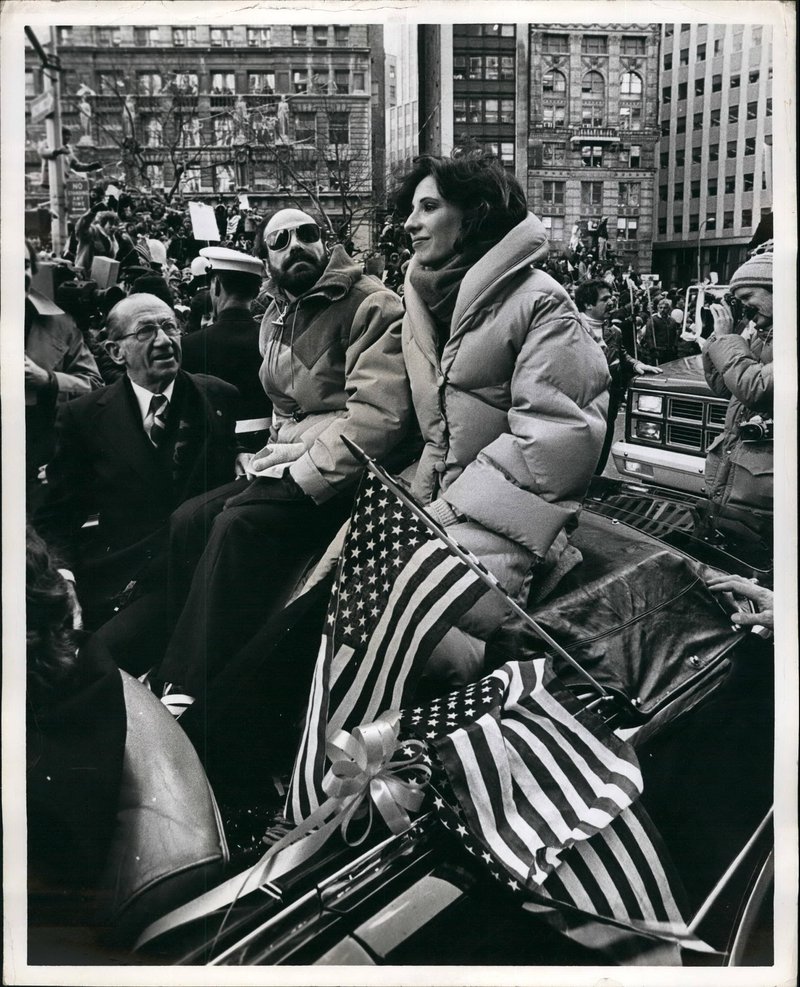

It would ultimately be more than a year before Barry was freed, on January 20, 1981. By then, Alexander was four years old, and Barbara left it to him to give a first statement to reporters. “What did we just find out?” she asked, cameras recording every word, to which he responded, “Daddy’s coming home.”

Her turn in the spotlight wasn’t over—there would be further interviews and the memoir to write with Barry following his return—but before long Barbara was ready to retire. “Everybody wants to be a star,” she said, with 40 years’ hindsight, “but I got a little taste of what that was like and I did not like it. I don’t want people to know who I am. I want to be able to walk down the street and just be part of the crowd.”