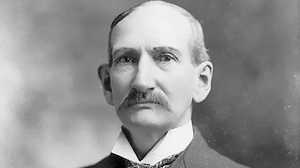

Allan Pinkerton's Detective Agency

Scottish emigrant and abolitionist Allan Pinkerton founded America's first detective agency and successfully brought down some of the country's most ruthless criminals. But in 1874 he tried to take on the James brothers, and he failed.

The man dubbed America's first "private eye" was born near Glasgow, Scotland, on July 21, 1819. Involved as a young man in radical politics, he was forced to emigrate to America in 1842. Pinkerton and his wife settled in the Chicago area, where Allan worked as a barrel-maker. By accident he discovered the lair of a gang of counterfeiters and had them arrested. The resulting celebrity led to his appointment as a deputy sheriff and then special agent for the U.S. Post Office, where his success in catching criminals continued. Around 1850 he formed Pinkerton's National Detective Agency, with the motto "We Never Sleep" and an unblinking eye as its symbol. This would lead to the description of independent detectives as "private eyes."

In addition to being a noted crime fighter, Allan was also a committed abolitionist. When in late 1858, John Brown freed 11 slaves in a raid on two Missouri homesteads and set out to take them to freedom in Canada, Pinkerton raised some $500 and arranged for transportation from Chicago to Detroit. His agency protected President-elect Abraham Lincoln during his trip to Washington to be sworn in, and Pinkerton served as chief of intelligence for Union general George mcClellan during the Civil War. After the conflict was over, Pinkerton's agency continued to grow; his agents infiltrated America's first-train robbing gang, the Reno brothers of Indiana, and he collected photographs of known criminals to aid in their apprehension and capture. In early 1874, after a train robbery by the James gang in Gads Hill, Missouri, the Adams Express Company asked Pinkerton to bring the brothers Frank and Jesse James to justice. Express companies were paid to carry valuables on the railroads, and they, rather than the train companies, typically suffered the largest losses during robberies. Pinkerton accepted the assignment and sent one of his detectives to Clay County, Missouri, to investigate.

Botched Raid

That detective, a man named Joseph Whicher, arrived in early March 1874 and made his way to the James homestead, despite being warned by a former sheriff that "the old woman [Zerelda] would kill you if the boys didn't." Whicher was found murdered the next day. His death scared off the express company, but not the old abolitionist Pinkerton, who vowed vengeance on the outlaws who still espoused the Confederate cause. "There is no use talking," he wrote of the James brothers, "they must die." In January 1875, a group of Pinkerton detectives and sympathetic locals raided the James farm, but their plans went awry when an incendiary device they tossed into the house exploded, wounding Zerelda and killing Jesse's eight-year-old half-brother Archie. Public opinion rallied to the James family as never before, and the Pinkerton agency was excoriated for the raid. Stung with his worst defeat, Pinkerton gave up the chase.

After the Raid

Allan Pinkerton died in 1884, just two years after Jesse James, but his sons William and Robert took over the running of the agency. Pinkerton detectives were often hired as muscle for factory management during bitter labor strikes. It was the bloodshed during the srtike at Andrew Carnegie's Homestead Mill in 1892 that led to laws in 26 states that banned bringing in outside guards during labor disputes. But the agency continued to flourish; by 1995 the company, which had switched its focus almost entirely to security services, had 250 offices and 50,000 employees worldwide.