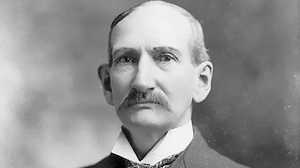

Biography: John Newman Edwards

An ex-soldier, alcoholic, and newspaper editor, John Newman Edwards spent the years after Confederate general Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse searching for ways to venerate the grand Confederate cause. He found the perfect vehicle in Jesse james, and Edwards was instrumental in creating the myth that the vicious bank robber was actually a noble Southern Robin Hood.

No Surrender

Born in 1839, Edwards was a native Virginian who came to Missouri in the mid-1850s to work as a newspaper printer. He became a hunting and fishing companion of a man named Joseph Shelby, and when war broke out and Shelby went off to fight for the Confederacy, Edwards served as his aide. Florid in speech and flamboyant in battle, Edwards had more horses shot out from under him than any other man in Shelby's command. When the war ended, Shelby and Edwards refused to surrender, crossing into Mexico and living in exile there for almost two years. Even from that distance, Edwards seethed at Northern Republicans; in 1866 he wrote that it was "only a question of time, I think, before the Radicals triumph and commence their devastating work upon the South." Little more than a year after Lee's surrender, Edwards was already trying to portray armed secessionists as innocent victims of the North.

Rallying the Troops

In 1867 Edwards returned to Missouri and resumed newspaper work, beginning as a reporter. Soon he took on the important political role of editor for the recently launched Kansas City Times. Edwards composed a glowing tribute to his former boss called "Shelby and His Men" and tried to convince ex-Confederates to get back into politics. When, at the end of 1869, he heard of an ex-bushwhacker named Jesse James who had used a bank robbery to try and avenge the death of guerrilla leader "Bloody Bill" Anderson, Edwards was intrigued. He made contact with the James brothers, and six months after the robbery, the first public statement from Jesse appeared in The Kansas City Times. In it the young outlaw asserted his innocence while simultaneously claiming that Unionists were the real criminals. This jibed perfectly with Edwards' own beliefs, and he began a campaign to convince the world that Jesse James was a valiant hero.

Creating a Myth

In the run-up to the election of 1872, Edwards devoted much of his editorial venom to denunciations of Republican President Ulysses Grant's "corrupt, tyrannical administration" and "the carpet bag dynasties" that Radicals were supposedly foisting on the South. But when he heard of Jesse's daring sunset robbery at the Kansas City Industrial Exposition, Edwards turned his attention back to the fierce rebel in a hyperbolic editorial called "The Chivalry of Crime." Edwards said bushwhackers might have "sat with Arthur at the Round Table" and called on readers to "revere" the robbers "for the very enormity of their outlawry." Soon Edwards, now a leading figure in the Confederate wing of the Democratic Party, was in full myth-making mode, printing a letter from Jesse in which he made the baseless claim that his gang members "rob the rich and give to the poor." In 1873 Edwards wrote a 20-page newspaper supplement glorifying the James gang, and he later tried to get a bill passed granting Frank and Jesse amnesty for their crimes. Edwards praised Jesse's plain wife as "young, accomplished, and beautiful," a "true and consistent Christian." And Jesse, who loved seeing his name in print, readily played the part Edwards had created for him, dressing in style and leaving press releases at the scenes of his crimes. He even named his son Jesse Edwards James.

Losing Interest

For all his bombast, Edwards had no desire to inaugurate another actual civil war; the newspaperman's objective was to instill pride in ex-Confederates and help orchestrate their return to political power. His lionization of Jesse James was a means to that end, and by 1880, the objective had been largely achieved. Reconstruction was over, and Missouri's legislature and congressional delegation were filled with ex-Confederates. When Jesse returned to crime after a few quiet years in Tennessee, Edwards no longer answered the outlaw's correspondence. Beset by severe alcoholism, Edwards managed to pen a fiery obituary after learning of Jesse's death, and he acted as intermediary in arranging for Jesse's brother Frank's later surrender to Missouri authorities. But Edwards' time, like Jesse's, was passing, and in 1889 the flamboyant newspaperman followed the outlaw he made legend into the ground.