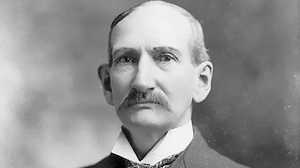

Biography: Jesse James

A teenager when he rode off to join Confederate guerrillas in 1864, Jesse James never really stopped fighting the Civil War. Unable to accept the defeat of the secessionist cause, Jesse trained his fury on banks, trains and stagecoaches. He fancied himself a modern Robin Hood, robbing from Radical Republicans and giving to the poor. But the myth hid the darker reality of a repeat murderer whose need for attention kept him committing crimes long after the cause he championed was gone.

Slave-Owning Family

Jesse was born in Clay County, Missouri, on September 5, 1847, to Zerelda and Robert James, hemp farmers who owned six slaves. When the Civil War came, young Jesse watched his older brother Frank march off to fight for the rebellion — and likely chafed that he himself was too young to go.

Confederate Fighters

Frank's activities with a band of pro-Confederate guerrillas brought the wrath of Union militiamen to the James family. Jesse was roughed up and his stepfather tortured for information. This may have been the spark that set off Jesse's flame. In the spring of 1864, the lanky 16-year-old with sharp blue eyes joined a bloodthirsty guerrilla group led by "Bloody Bill" Anderson. They terrorized pro-Union enemies in the Missouri countryside. Still an impressionable teenager, Jesse participated in multiple atrocities, including the notorious Centralia massacre, in which 22 unarmed Union soldiers and a hundred other Union soldiers were butchered. These experiences helped define the man he would become.

Bold Robbers

Many, if not most, of the guerrillas returned to civilian life after the war ended, putting down their weapons and picking up their plows. But Jesse and Frank James felt no peace. The humiliation of Confederate defeat still gnawed at them, and the disenfranchisement of most ex-Confederates by the victorious Radical Republicans made Jesse feel like a victim. He chose to continue fighting, targeting a bank in Gallatin, Missouri, thought to be run by the man who had killed Bill Anderson. On December 7, 1869, Jesse and Frank rode in during daylight, shot an unarmed cashier, and made off with some worthless paper. They made a daring escape through the midst of a posse sent to capture them. Later they declared that "they would never be taken alive." For the first time, the newspapers mentioned Jesse James and he loved the attention. Soon he began tailoring his robberies to attract as much of it as possible, even leaving press releases behind.

The Legend Begins

Aided by an ex-Confederate soldier and newspaper editor named John Newman Edwards, Jesse began constructing a myth of himself as a heroic Southern fighter, a noble Robin Hood who helped poor Missourians crushed under the weight of Republican outrages. In letters that Edwards published, Jesse simultaneously proclaimed innocence for specific crimes while wearing the general outlaw's mantle. "We are not thieves," he wrote, "we are bold robbers. I am proud of the name, for Alexander the Great was a bold robber, and Julius Caesar, and Napoleon Bonaparte." It was indeed the stuff of legend; while Jesse certainly stole from the rich, there was no evidence he ever actually gave his gains to the poor.

Northfield

During the early 1870s, Jesse and his gang robbed banks, stagecoaches, and trains with near impunity. Sheltered by Confederate sympathizers, they eluded authorities again and again. Perhaps Jesse began to believe in his own invulnerability, because in September 1876 he badly overreached, attempting a bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, some 500 hundred miles from his normal base of operations. The robbery was a disaster. The townsfolk had no tolerance for former rebels — they killed two of the robbers then and there, and hunted down the others. Only Jesse and Frank escaped, but they were forced to live in Tennessee under assumed names.

Gunned Down

Frank began to enjoy the quiet life, but Jesse was restless, unable to settle down with his wife Zee and son Jesse. He tried various moneymaking schemes, bought race horses -- but none of it quenched his thirst for the spotlight. Jesse returned to crime in 1879, but by then ex-Confederates had taken over Missouri's political reins, and the public had little patience for his banditry. Jesse's new gang, none of them ex-soldiers, were in it for the money, not the cause, and one of them happily conspired with Missouri's governor to hunt the outlaw down and collect a $10,000 reward. On April 3, 1882, Jesse got a bullet in the back of the head. He died with few allies, but in later years the myth surrounding him grew so strong that it eventually crowded out the inconvenient truths of his own murderous life.