JFK's Early Days

In April 1954, John Fitzgerald Kennedy addressed his fellow senators on the situation in Indochina. It was not surprising, he said, that the French had failed to control a Communist insurgency there. In order to resist communism, the people of Indochina needed not more guns, but the freedom to govern themselves.

Years later, partly due to Kennedy's role in Vietnam, his remarks proved to be tragically prophetic. Yet his speech that day was emblematic of the development of John F. Kennedy himself. The sickly, bookish child, the adolescent rebel and collegiate playboy had grown into a serious politician. Still sexually driven, still self-absorbed, he had become a man with the power to change the world. Many of the people who knew Kennedy in his earlier years would have been surprised at the transformation.

Born on May 29, 1917, in Brookline, Massachusetts, John Fitzgerald Kennedy grew up in a family defined by fantastic wealth, Roman Catholicism, Democratic politics, and patriarchal control. Kennedy's father, Joseph Kennedy Sr., had made a fortune on Wall Street and in Hollywood, and he drove his nine children to compete and to win with the same relentlessness that he pursued money and beautiful women. Joseph's wife Rose, daughter of former Boston Mayor John Fitzgerald, had her own obsession -- maintaining the Kennedys' image as the perfect family despite her husband's distance and infidelity.

From the very beginning, John Kennedy, or Jack as the family called him, suffered frequent illness. At two, he nearly died from scarlet fever. Like his siblings, Jack enjoyed sports, but he seemed to prefer reading. He possessed a keen intelligence, a gift for creative wit, and a buoyant charm.

Educated at private schools, Jack chafed under authority and suffered from academic disinterest. At Choate, a boys' preparatory academy, Kennedy became a magnet for troublemakers. Untidy and rebellious, he made a distinctly negative impression on the Choate faculty. He consistently earned mediocre grades, and his father worried that Jack might never reach his potential.

After Choate, Jack headed for Princeton. There, he continued to cultivate what had by then become an obsession -- the pursuit and conquest of eligible females. But illness ended his Princeton career within weeks.

The problem was Addison's disease, a malady which had plagued him for years, causing weakness, weight loss, blood problems, and gastrointestinal distress. Addison's disease tortured John Kennedy for decades before it was successfully diagnosed. Several times, it nearly killed him. This time, however, Kennedy's health improved within a matter of months. He returned to college, this time at Harvard, where his older brother Joe had already made his mark.

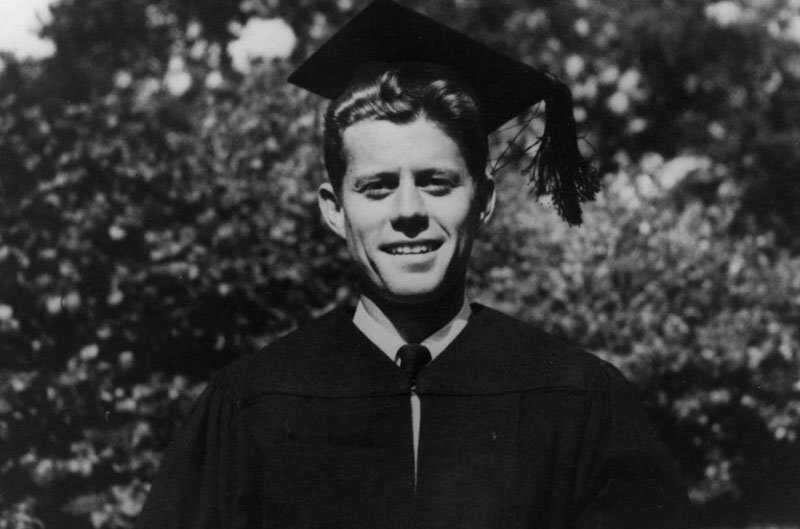

Jack Kennedy arrived at Harvard in the fall of 1936. He quickly dispelled any notions that his academic career would be a serious one. Instead, he concentrated on the social scene, where his charm, good looks, and wealth brought him success with women. Despite his scrawny physique, he managed to win a position on the freshman football team, where he played with tenacity, but little effect.

During a tour of Europe following his freshman year, Jack began to show an interest in international politics. He visited Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany. He questioned refugees from the Spanish Civil War about conditions under Franco.

Two years later, Kennedy traveled to France, Poland, Latvia, Turkey, Palestine, Russia, and Germany. He wrote long, detailed letters to his father, now Franklin Delano Roosevelt's ambassador to the Court of St. James, about the trouble between Germany and Poland, life in Communist Russia, and the Zionist movement in Palestine.

By early 1940, when Jack began his last semester at Harvard, most of Europe had been crushed by the Nazi war machine, and Britain lay under siege. Ambassador Joseph Kennedy faced harsh public criticism for his appeasement of Hitler, as well as for his public assertions that Britain would be destroyed by the Nazis. But Jack Kennedy had his own ideas about England's response to Hitler's rise to power, and he developed them in his Harvard senior thesis.

Published and promoted by Joseph Kennedy. Sr., Why England Slept, became a national bestseller. In the book, author John F. Kennedy argued that it was the isolationist character of the British population as a whole, and not Britain's political leadership, that had led to Hitler's appeasement. This isolationist tendency, compounded by the sluggish nature of democracy, had delayed the buildup of Britain's military and allowed Hitler to gain the upper hand.

Lauded by some reviewers as perceptive, condemned as simplistic by others, Why England Slept demonstrated that Kennedy was capable of organized, purposeful direction. At a time of international turmoil, he had shown the courage to buck the intellectual tide. Jack was continuing to develop politically. World War II would be the springboard to a full time political career.

Jack joined the Navy in the fall of 1941. Two years later, he became a certified American hero. As commander of motor torpedo boat PT 109, he had kept his men safe behind enemy lines after the boat was rammed and sunk by a Japanese vessel. The incident made him famous. In 1946, at the urging of his father, Kennedy parlayed his hero status into a Massachusetts Congressional seat.

"We're going to sell Jack like soap flakes, " Joe Kennedy said, and sell him they did. Joseph Kennedy built his own political machine from the ground up, called in numerous political debts, and pumped thousands upon thousands of dollars into his son's campaign. Although he disliked campaigning and his back problems were severe, Jack Kennedy worked hard, and his good looks and charisma helped deliver him a victory.

In Washington, Congressman Kennedy became a darling of the social scene. At work in the House, he supported the kind of liberal domestic programs -- health care, housing, and labor -- that were important in his working-class district at home, but foreign policy remained his true interest.

In 1952, with the support of his father's political machine, Kennedy won a seat in the Senate. Containing the Communists abroad became a focus of his career. Kennedy, who had toured Asia as a Congressman and witnessed colonial oppression firsthand, believed that offering young nations freedom and development aid could stop the spread of communism.

When Senator Kennedy addressed his colleagues on that day in April, 1954, he delivered an eloquent plea for American support of self-determination in Indochina. "No amount of American military assistance," he said "can conquer an enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere," he warned.

Clearly, Jack Kennedy had grown. The relentless pursuit of women continued. The attraction to the society life remained. But the senator from Massachusetts had developed a vision which would help drive him to the White House. As president, he would struggle, often unsuccessfully, to implement that vision. He would die with it unfulfilled.