He Met His Wife Over a Lie Detector. Then Things Got Interesting.

Leonarde Keeler, the inventor of the Keeler Polygraph, spent most of his life trying to tell if people were telling the truth. It turned out to be trickier than hooking them up to a machine.

This article is the first in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

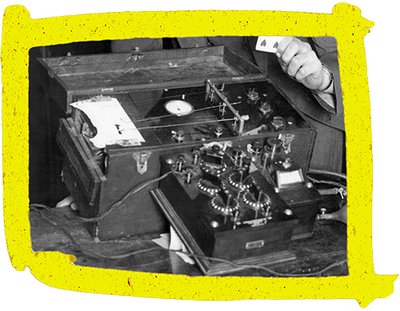

He, rakish and wearing a three-piece suit, looks at the four of hearts in his left hand. She, dark hair in finger waves, ignores the playing card to smile at him. The two are connected by the machine between them: a breadbox-sized contraption full of dials and switches. The image, taken around 1935, is a staged recreation of the first time the couple met—also over a lie detector machine, also with him trying to play a card trick. She saw right through the trick that first time, too.

Leonarde Keeler and Katherine Applegate were students at Stanford University when they met in 1925. Leonarde wasn’t like the other undergrads. For one thing, Keeler had already been on the front page of the Los Angeles Times when he was barely out of high school. The newspaper identified him as the inventor of what it newly dubbed a lie detector. In L.A., Keeler reported directly to the city’s reformist police chief, August Vollmer, who claimed the machine would provide a “modified, simplified and humane third degree.” Vollmer hoped his protégée’s mechanical innovation would make fallible and violent interrogations a thing of the past.

When Keeler left Los Angeles to enroll at Stanford, he set out to refine his instrument. It wasn’t just the lie detector’s accuracy he wanted to improve; it was also the machine’s commercial application. Keeler wanted to make the technology salable. That started by taking its mechanisms and packaging them in a portable walnut case. He poured his savings into building a prototype device and submitted a patent application.

Keeler’s true refinements, however, were to the smoke and mirrors of the lie detector’s operation, and for practice with that he had his fellow students. He gave his test subjects playing cards and asked them to select one. Once they were hooked up to his machine, he presented them with each card in the deck, instructing them to deny having selected any of them. Presumably, the denial of the one they had chosen would provide the baseline reading of a “lie.” Still, he sometimes rigged the deck to be sure.

One classmate saw through his sleight-of-hand. Katherine Applegate avoided looking at the card she selected—her denials, as a result, were all true. Keeler and Applegate became friends. Both bon vivants, they liked to socialize, drink and move fast—she on horseback, both of them driving. He would cut class for flying lessons; Applegate too took lessons and later became an accomplished pilot.

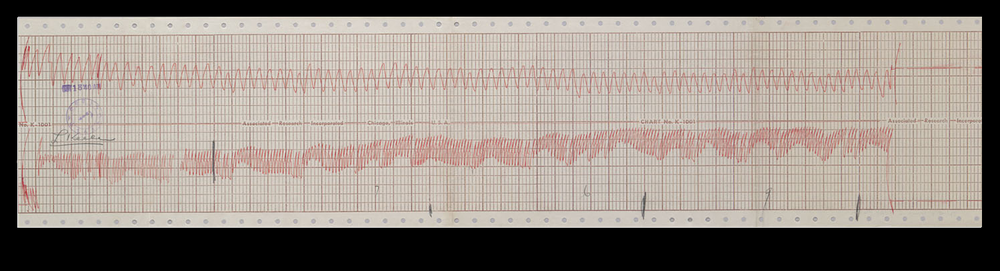

Several years later they grew romantically involved, then married in 1930. That same year, Keeler explained the true inner workings of his machine, which had nothing to do with the appliance. “The success of this device in detecting deception and guilt,” he said, “is attributed in large measure to the psychological effect such a test has in bringing about confessions.” Intended to sanitize police interrogations, his device instead became another tool in an officer’s coercive arsenal.

By then Leonarde and Katherine had moved to Chicago, then known as Murder City for its gangs and staggering homicide rates. In 1929, looking to turn the city’s reputation around, civic leaders established the Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory at Northwestern University, the country’s first formal institution for criminal investigation. The Keelers became two of the lab’s leading criminologists, Leonarde its lie detection specialist, Katherine an expert handwriting analyst.

Chicago was the perfect milieu for the dashing, crime-fighting couple. Spending time with them always involved “excited talk about specimens of handwriting, fingernail scrapings, gunpowder, explosions and corpses,” recalled Keeler’s sister Eloise in Lie Detector Man, a biography published after his death. By now Leonarde’s machine had a formal name—the Keeler Polygraph—and a built-in public relations department in the crime detection lab. Within two years, lie detection was the Northwestern lab’s most lucrative concern. What’s more, Leonarde and Katherine both regularly appeared in the news for their forensic exploits.

The photo recreating their meet-cute accompanied just such an article in the March 13, 1937 issue of Newsweek about one of the most controversial cases of Keeler’s career.

Chicagoan Joseph Rappaport was sitting on death row, convicted of murdering an informant set to testify against him. Under pressure from Rappaport’s family and religious community, Governor Henry Horner had already delayed Rappaport’s execution five times. Horner told Rappaport’s sister he would consider another stay—if the condemned man passed a test performed by preeminent lie detection specialist (and personal friend) Leonarde Keeler.

Just before the scheduled execution, Keeler put Rappaport to the test, starting with his standard card trick. After two hours of interrogation, Keeler called the governor with his verdict: Rappaport was guilty. Another two hours later, Rappaport went to the electric chair.

The story made for scintillating copy, but some journalists, and Keeler’s colleagues, were incredulous about what they saw as his complete ethical lapse—it seemed mad to test someone on a polygraph machine with the threat of their potential execution several hours away.

The scene of the Newsweek image belied another of Keeler’s oversights. By the time it appeared, his marriage was on the rocks—Katherine had been cheating on him for years, with numerous lovers. Her infidelity was staring Leonarde in the face, and somehow the lie detector man had missed it. Perhaps he had convinced himself of his skill at divining people’s truths.

“Professor Keeler’s card trick works nine times out of ten,” reads the Newsweek caption on the photo, a statistic of dubious veracity likely provided, conveniently, by Keeler himself.

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.