Meet the Players: US Federal Government

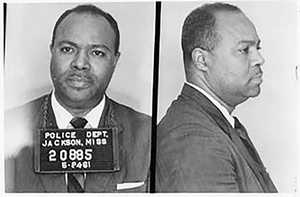

J. Edgar Hoover

The first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation whose power base extended past presidential authority, J. Edgar Hoover was a racial conservative who considered many Civil Rights Movement activists to be dangerous subversives and Communist sympathizers.

Claiming that the FBI was "not a protection agency," Hoover had ordered agents to avoid intervening in civil rights crises and to limit their activities to observation and note-taking. In addition, he had ordered surveillance of several key figures in the movement, including Martin Luther King, Jr..

Hoover chose not to pass along intelligence received from Klansman and FBI operative Gary Thomas Rowe to Attorney General Robert Kennedy about the planned May 14 riot at the Birmingham Trailways Bus Terminal, giving the Kennedy administration no way to prevent the violence. At the May 20 riot at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station, Hoover's FBI agents stayed inside several parked vans taking pictures. The agents' film later turned out to be defective.

J. Edgar Hoover served as Director of the FBI for mare than 40 years, through the terms of 9 presidents.

Robert F. Kennedy, Brookline, MA

Robert F. Kennedy became Attorney General in January 1961, after his brother John F. Kennedy won election as President of the United States. Robert Kennedy had given a speech expressing the administration's support of civil rights to a Southern white audience a few days after the start of the Freedom Rides on May 6. However the issue was not yet a major priority for a Kennedy White House preoccupied with Cold War politics.

Caught off guard by the violence that erupted during the May 14 Anniston, AL bus burning and the riot at Birmingham Trailways Bus Station, Robert Kennedy dispatched special assistant John Seigenthaler to Birmingham, AL to aid the embattled CORE Freedom Riders. Seigenthaler helped arrange a plane flight from Birmingham to New Orleans, LA. Robert Kennedy sought protection for the Riders by Alabama state officials like Gov. John Patterson, with limited success, eventually sending in U.S. Marshals to protect the Riders during the May 21 siege and firebombing of the First Baptist Church.

Kennedy's avowed wish was for a "cooling off" period, in which civil rights leaders pursued voting rights issues rather than conducting violence-provoking direct action that embarrassed the United States on the world stage. He struck a compromise with Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland, allowing the Riders to be jailed in exchange for the Riders' safety, explaining that the Federal Government's "primary interest was that they weren't beaten up."

On May 25, 1961, Robert F. Kennedy delivered an idealistic radio broadcast for Voice of America, defending America's record on race relations to the rest of the world, insisting that "there is no reason that in the near or the foreseeable future, a Negro could [not] become President of the United States."

Just four days later, on May 29, he formally petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to adopt "stringent regulations" prohibiting segregation in interstate bus travel. The proposed order, issued on September 22 and effective on November 1, removed Jim Crow signs in stations and ended segregation of waiting rooms, water fountains, and restrooms in interstate bus terminals later that same year, giving the Freedom Riders an unequivocal victory in their campaign.

The Freedom Rides campaign was an opportunity for the Kennedy brothers to begin building a rapport with civil rights leaders through phone conversations, meetings, and cautious collaborations. These ties to the Civil Rights Movement would only deepen in the coming years.

In 1964, Robert F. Kennedy was elected as U.S. Senator for New York. He was assassinated on June 5, 1968 while he campaigned for President.

John F Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy had campaigned in part on a moderately pro-civil rights platform, but in the spring of 1961, his first priority was Cold War politics. Kennedy wanted to avoid embarrassing headlines in the weeks leading up to his June summit meeting in Vienna with Soviet premier Nikita Kruschev.

"Can't you get your Goddamned friends off those buses?" Kennedy complained to Harris Wofford, a Justice Department official close to the Civil Rights Movement. "Stop them."

Even as Alabama Governor John Patterson dodged Kennedy's phone calls, the President and other administration officials worked to guarantee the physical safety of Freedom Riders, deploying U.S. Marshals to protect the Riders during the May 21 siege and firebombing of the Montgomery, AL First Baptist Church and mobilizing the National Guard. His administration permitted the Freedom Riders to be imprisoned in Mississippi on flimsy breach-of-peace charges, but also put pressure on the Interstate Commerce Commission to remove Jim Crow signs and end segregation of interstate bus travel facilities.

The events of the Freedom Rides paved the way for the administration to align itself more decisively in support of Civil Rights. Kennedy sent federal troops to the University of Mississippi in 1962 and the University of Alabama in 1963, to protect black students attempting to enroll. On June 11, 1963, Kennedy gave a speech calling upon Congress to pass a comprehensive Civil Rights bill, stressing that Americans were "confronted primarily with a moral issue, not a legislative or political one."

The resulting legislation would be passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

John Seigenthaler, Nashville, TN

John Seigenthaler was a native of Nashville, TN who worked as a newspaper reporter at The Nashville Tennessean prior to working with Robert Kennedy on a committee investigating organized crime. In January 1961 he became a special assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Seigenthaler described his privileged upbringing and how it left him blind to the problems of Jim Crow.

"I grew up in the South, the child of good and decent parents..." he recalls in Freedom Riders. "I don't know where my head or heart was, or my parents' heads and hearts, or my teachers'. I never heard it once from the pulpit. We were blind to the reality of racism and afraid of change."

As special assistant to the Attorney General, Seigenthaler initially served as the intermediary between the federal government, the Freedom Riders, and white segregationist state officials. His task was to convince the Freedom Riders to cease their direct action and accept a "cooling off" period, while ensuring their physical safety from mob violence. The administration believed that as a white Southerner from Tennessee, Seigenthaler would share a common bond with Governor Patterson of Alabama and other members of the Deep South establishment.

"I'd go in, my Southern accent dripping sorghum and molasses, and warm them up," he explained.

Seigenthaler successfully arranged for the original CORE Freedom Riders to depart from Birmingham on May 15 by plane, after a lack of willing bus drivers had blocked their progress. However, he soon learned that the federal government held little sway on the issue of race relations in Alabama. He was knocked unconscious while attempting to aid two Freedom Riders during the May 20 riot at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station, after telling assailants to stop and respect his authority as a federal official.

Seigenthaler went on to work on Robert Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign, before returning to journalism. He later became editor, publisher, and CEO of Nashville's The Tennessean and founding editorial director of USA Today. He founded the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University in 1961 with the mission of creating national discussion about First Amendment rights and values.