Women in the Mine Towns

In the Mine Wars that erupted in southern West Virginia over the first two decades of the 20th century, coal miners and coal companies in West Virginia clashed in a series of brutal conflicts over labor conditions and unionization. The coal miners were a diverse group of men who came from farms in Appalachia, Eastern Europe, and the American South to begin work in the coalfields of West Virginia, where mines were opened in remote areas that often lacked existing towns. Coal companies established towns and imposed a system of rules; miners could be evicted from their company-owned home if they broke the rules. The coal company officials believed that it was their right to control the management of the coalmines. Miners argued that they had the right to discuss unionization and join a union. Within this context, the union movement in southern West Virginia counted women among its strongest supporters and organizers.

Women in the early 1900s were barred from working underground in the coalmines, but their work above ground was integral to the coal camp system. In many cases, a wife's unpaid labor made it possible for the miner to do his job. Women prepared the food that the miners brought to work, and they cleaned the miner's clothes. They managed to support their children on what little pay the miner brought home, often dealing with the monopolistic prices at the company store. Depending on the coal camp, they were tasked with hauling water from nearby creeks or water pumps up to their homes for drinking and bathing. Unlike women who worked in urban factories and lived in tenements, coal miner's wives lived at their husband's workplace -- the coal company often owned the entire coal camp, including the miners' homes. They faced the looming threat of eviction, as well as the chance that their husband or son might be severely injured or perish in the mine. As Chuck Keeney, great grandson of labor organizer Frank Keeney, recalled during his 2014 interview for the documentary The Mine Wars, "these were women who had to deal with harsh circumstances, and they themselves had to have a certain type of toughness, not just physical toughness, but a psychological toughness."

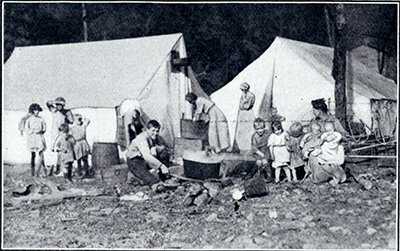

When strike organizers in the early 1900s decided to protest the conditions in the coal camps, the strikes had a significant impact on the lives of women. Striking miners and their families were evicted from their company-owned homes and forced to live in tent colonies set up by the union. The tents were erected on whatever private land could be found near the mines.

Thomas Andrews explained during his 2014 interview for The Mine Wars that "there was a purpose for these tent colonies beyond simply sheltering people. They were also supposed to keep the foot soldiers in these strikes, the strikers, near the front lines." Women kept the strikers on the front lines by supporting daily life in the tent colonies. They cooked, did washing, and raised children in the tents. Their commitment to the strike was not rhetorical; it meant a material change in their daily lives.

In addition to carrying on their household duties in challenging strike circumstances, women also took action to protect the integrity of the strike. The success of the strike depended on the miners' ability to make the company keenly aware of their absence and the loss of productivity, and to compel the company to make concessions in the interest of quickening the miners' return to work. However, coal companies in southern West Virginia, seeking to fulfill their contracts and maintain production, tried to replace the striking workers with new recruits called "transportation men." Wives and daughters would tear up train track, curse at the new recruits, and generally prevent them from entering the mines. Grace Jackson, interviewed during an oral history project in the 1970s, remembered women wielding guns when trains carrying new workers arrived: "The women and the men got their high-powered rifles, and they got on their bellies and laid on each side of the track... and when that train went through... they let one shot fire [and the transportation men] all turned loose."

Willie Helton, another woman living in the coalfields at that time, recalled using her dress as effective cover for transporting guns: "And I slipped one gun down into my dress on this side. I had one gun on either side of me, and I had a pocket full of shells. I couldn't hardly walk." Both of these memories highlight the fact that both men and women were active participants in the labor conflict.

One of the most famous women in the southern West Virginia coalfields was not a miner or a miner's wife. She was a woman named Mary Harris "Mother" Jones. Her husband and children's deaths in the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1867 left her without family obligations, and she devoted herself to fighting for workers' rights. She became involved with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), and in speeches throughout the coalfields, Mother Jones utilized a visceral form of maternalist politics to advocate for miners. Adopting the character of a universal mother, Jones questioned the courage and masculinity of coal miners who were reluctant to join the union. "If you are too cowardly to fight, I will fight," she told coal miners on the steps of the capitol building in Charleston, West Virginia in 1912. To recalcitrant miners she added, "You ought to be ashamed of yourselves... to see one old woman who is not afraid of all the blood-hounds."

Mother Jones' and other female organizers' intellectual and political commitment to their cause invited sexist criticisms at the time. A New York Times reporter expressed surprise in 1913 when he listed the contents of Mother Jones' purse: "comb and brush and powder puff. She has a powder puff. That, too, astonished me." Mother Jones' ownership of a powder puff evidenced an interest in her appearance that was at odds with the journalist's expectations. If a female UMWA organizer like Fannie Sellins entered a coal camp, she was chided that it was not a fit place for any decent woman. Her interest in organizing the miners and her visits to coal camps in Collier, WV, precluded her, in the mind of a federal judge, from being regarded as a moral woman. Sellins was later killed during a conflict with police while picketing with steelworkers in Brackenridge, Pennsylvania.

Mother Jones was perhaps the most notorious female labor organizer in the coal camps, but she certainly wasn't the only vocal woman in the labor movement. Pauline Newman started working at the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Company at the age of eight, and when the New York City factory burst into flames in 1911, she was out campaigning for worker safety and the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) in Philadelphia and soon joined a federal group to investigate the fire. As the number of women wage-earners increased, rising by 43% from 1900 to 1910, there were also more possibilities for unionization. Women like Clara Lemlich, a Ukrainian immigrant, proclaimed, "I am a working girl... one of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions." Increasingly, women not only fought for better working and living conditions for men and children, but also for themselves.