Remembering the Neshoba Murders in Black and White

Five decades of calling for justice for James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman

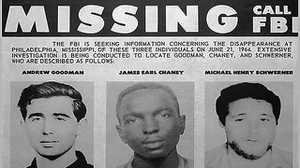

In June of 1964, Philadelphia, Mississippi was thrust into the national limelight. Three civil rights workers were missing after their June 21 visit to investigate the burning of Mt. Zion Methodist church in a neighboring Neshoba County Black community.

After 44 days of searching, on August 4, the FBI uncovered the bodies of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. By November, federal authorities had signed confessions from two of 21 alleged perpetrators, recounting in excruciating detail how Klansmen, including local law enforcement officers, had intercepted the three young men as they attempted to leave the county, took them from their car, drove them in a Deputy Sheriff’s squad car to a remote dirt road, shot them at close range and buried them deep within an earthen dam.

Most locals refused to cooperate with the federal investigation. Despite the evidence, many believed the deaths of the three civil rights workers had been the result of a northern conspiracy, not a homegrown plot. The previously obscure Southern town of Philadelphia, Mississippi became a national emblem of segregationist society. In December of 1964, Philadelphia was profiled in LIFE Magazine as a “strange, tight, little town loath to admit complicity.”

For a generation, according to historian Howard Ball, this reputation persisted. White Neshoba Countians upheld a conspiracy of silence, steadfastly refusing to discuss the events or teach children about the racial violence that precipitated this national reputation. For Ball, Anne Pullin, the “everyperson” waitress at Peggy’s Restaurant in downtown Philadelphia summed up the climate. “For 30 years no one spoke of the murders and then, in 1989, ‘boom’--everybody began talking about what happened a quarter of a century ago. It was as if everybody in Philadelphia and its environs had come out of a collective coma.”

But this is only part of the story. Neshoba County’s Black residents and their allies refused to be silent in 1964 and have commemorated the murders and called for justice ever since.

Eight weeks after Klansmen burned down Mt. Zion, parishioners gathered among the ruins. Sitting underneath the towering oak trees, some visibly scarred from the flames, Black residents commemorated the lives and loss of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, whose bodies had been discovered just days before. Sheriff Lawrence Rainey and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, both suspects in the murders, looked on from a distance. James Chaney’s 11-year-old brother, Ben, spoke defiantly: “I want us all to stand up here together and say just one thing. I want the sheriff to hear this good. We ain’t scared no more of Sheriff Rainey!”

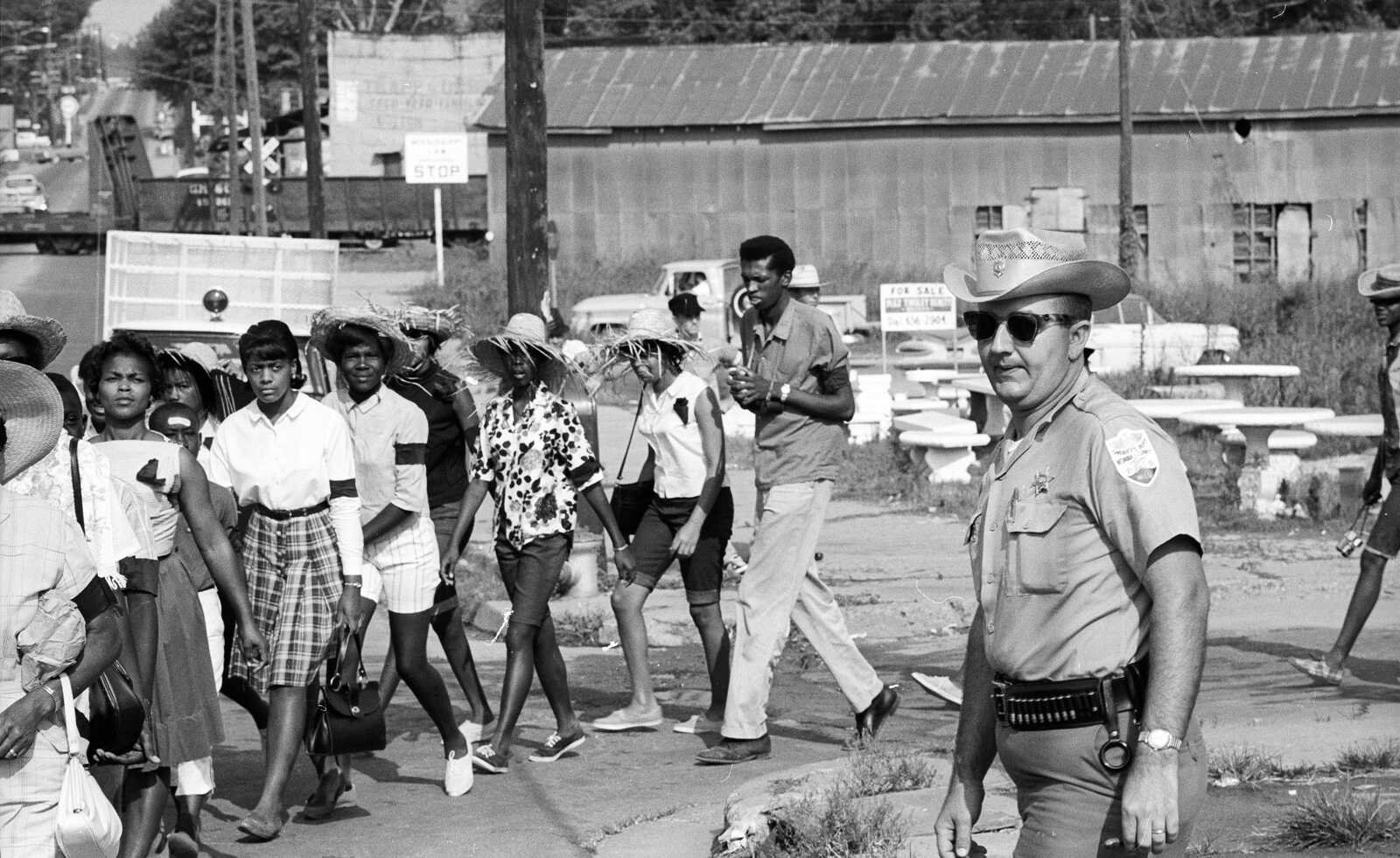

A year later on the first anniversary of the murders, some 200 people gathered again at Mt. Zion and began an annual tradition. The crowd of mostly local African Americans marched some 10 miles from Philadelphia’s Independence Quarters to Mt. Zion. There they met a memorial motorcade of over 50 civil rights workers who had driven from Meridian, to the Neshoba County Courthouse and then to the ruins of the burned church. Assembling around stone steps—just about all that was left of the original church—they sang freedom songs. Again, Deputy Sheriff Price was looking on, this time from behind the wheel of his truck, a gun rack behind his head cradling a submachine gun.

On the second anniversary of the murders, commemorating marchers, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., came under attack as they attempted a similar procession from Independence Quarters to Mt. Zion. Whites threw stones, bottles and firecrackers at King as he spoke from the curb outside the jail where Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman had been held the night of their death. As the procession approached the court house square, two young white men in a red convertible drove past the line of the march, skidding towards the marchers and missing them by inches. Minutes later, white men in a pickup truck cruised past the line, striking marchers with a wooden club. Fearing for his safety, King aborted the march, returning three days later to try again. With some 300 marchers, he attempted the same route and was repeatedly stymied by hostile whites who were virtually unrestrained by local law enforcement. King would later describe these events in Philadelphia as some of the most frightening of his life.

In December of 1972, spectators gathered outside Mt. Nebo Baptist Church, where King began his march six years earlier. They had gathered for the unveiling of a new memorial that their nickels and dimes had helped erect. The memorial was the product of grassroots effort initiated by Mt. Nebo, which stood just blocks from the Freedom Democratic Headquarters ( in Philadelphia’s Independence Quarters, and was a triumph for longtime local activist Lillie Jones who believed that there should be a monument to the three civil rights workers at every church in Neshoba County.

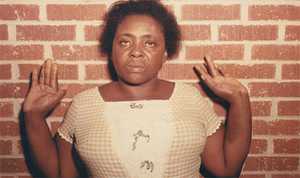

And while Ms. Jones’ wishes may not have come to pass, the congregants of Mt. Zion later erected their own private monument, keeping the memory alive through annual commemoration services. Come each spring, Mable Steele, who took a special interest in honoring the three civil rights workers, spearheaded preparation for Mt. Zion’s annual memorial program—a charge she continued until her death. She, along with her husband, Cornelius, had been primary contacts for Michael Schwerner and James Chaney during their dozens of visits to Mt. Zion between February and June of 1964 and were among those beaten by Klansmen on the night of June 16, 1964. Their son, John Steele, would later continue the family tradition of organizing the annual commemoration.

Alongside these persistent commemorative efforts at Mt. Zion and Mt. Nebo, Neshoba County’s white officials and community leaders remained silent on the murders until 1989. That year the city, county and Choctaw tribe co-sponsored a community-wide commemoration marking the 25th anniversary of the murders.

Alan Parker’s Oscar-winning film, Mississippi Burning, which is based on the 1964 murders, had been released on December 9, 1988, reinvigorating national interest in the case and sparking a debate over the film's historical inaccuracies. Critics charged that the film obscured the importance of Blacks in the civil rights movement, misportrayed the tactics of FBI investigators and unfairly depicted all white southerners as racist.

Locally, Stanley Dearman, the owner and editor since 1966 of the local newspaper, the Neshoba Democrat, was keenly aware of this awakened national interest. As each anniversary approached, he fielded questions from eager reporters interested in tracking Philadelphia’s racial progress. The release of the film intensified this effect, and national news coverage sky-rocketed as did reporters' interest in visiting the town. When it became clear to Dearman that hundreds of visitors planned to travel to Philadelphia for the 25th anniversary, he recognized an opportunity. Publicly acknowledging the murders could change the national narrative, and more importantly for Dearman, right a decades-old wrong. In 2005, Dearman reflected on the murders: “I can say without exaggeration that in 40 years, not a single day has gone by that I don’t think about those boys...It’s just something you can’t wash off. People may not want to talk about it, but it will never go away. The thing won’t let us forget.”

As the 25th anniversary approached, Dearman elicited the support of Dick Molpus, a native Philadelphian and recently elected Mississippi Secretary of State, to co-chair the commemoration planning task force. Ultimately, a diverse coalition emerged, consisting of white businessmen and civic leaders, as well as representatives from Mt. Zion and the local branch of the NAACP. Along with financial and logistical support from the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania mayor’s office “sister city” participants, who had taken an interest in the project, the group organized the first commemoration that drew participation from Neshoba County’s white civic institutions.

On June 21, 1989, over 1,000 people from around the country descended upon Philadelphia, among them planeloads of VIPs from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and over 13 chartered buses from New York City. And while some local Black residents attended, many stayed away. They were skeptical of the white leaders' sudden interest in the murders and curious to see what, if anything, would accompany a day of symbolic gestures.

The program began outside Mt. Zion, the structure rebuilt to replace the one torched by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. Perched on a temporary stage, civil rights veterans, community members and family members of the slain civil rights workers withstood the blistering Mississippi heat to address the audience. The message from Michael Schwerner’s widow, Rita, was simple and stern. “This is the very first time in my life a Mississippi highway patrolman waved at me.”

The day included the first public apology for the murders from an elected government official. Dick Molpus had returned to his hometown to speak directly to the families of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman. “We deeply regret what happened here 25 years ago,” Molpus said before the crowd. “We wish we could undo it. We are profoundly sorry that they are gone.”

When employees of the local newspaper arrived at work the day after the commemoration, they were confronted by an ominous message. The white columns flanking the entry to their downtown office had been defaced with red spray paint spelling “K-K-K.” Within three days of the event, Dick Molpus received 26 death threats and was compelled to retain a security detail to protect him and his family, who had also received threats. When he ran for governor five years later, he failed to carry his hometown.

Outside of the dedication of a state-sponsored historical marker at Mt. Zion Church immediately following the 1989 event, white community leaders and officials did not take commemoration any further. African American churches continued to commemorate the event annually as they had since 1964.

1989 also marked a turning point in the legal investigation surrounding the case. After watching Mississippi Burning, Mike Moore, the state’s attorney general, commissioned a confidential report to determine whether enough evidence was available to reopen the case. The report’s authors, Mississippi Special Assistant Attorneys General John R. Henry and Jack B. Lacy, concluded that there was. Yet after the report leaked, Moore equivocated. While he affirmed the report’s findings, he found that “it is not in the best interest of the people of this state” to prosecute and soon dropped the case.

Over the next decade, the victims’ family members continued to press for legal justice, including Ben Chaney, who in 1997 sent a letter urging Attorney General Moore to reinvestigate the case. But an assistant to Moore told Chaney the Attorney General’s “office does not have the authority to reopen the case.”

It wasn’t until 1999 that new information and a growing public interest in civil rights-era crimes propelled the case forward. In 1999, Jerry Mitchell, a reporter for the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, acquired and published a transcript of a previously sealed interview with Sam Bowers, the former imperial wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. In it, Bowers boasted that he had “obstructed justice” in the probe of the Neshoba County murders and was “quite delighted to be convicted and have the main instigator of the entire affair walk out of the courtroom a free man.” That instigator was Edgar Ray “Preacher” Killen who had coordinated the killings and narrowly escaped justice in the 1967 federal trial when one member of the all-white jury refused to convict him on the grounds that she could never convict a preacher.

After two years of building their case against Killen, the Attorney General’s efforts suffered a fatal blow. The prosecution's main eye witness, Cecil Price, the former Deputy Sheriff, fell from a cherry picker at his workplace and died at the age of 63. Within days of Price’s death, Moore signaled that his office was closing the investigation. “We’ve still got the zeal to do it,” said Moore, “but there’s no sense in doing it if you can’t make a strong case.”

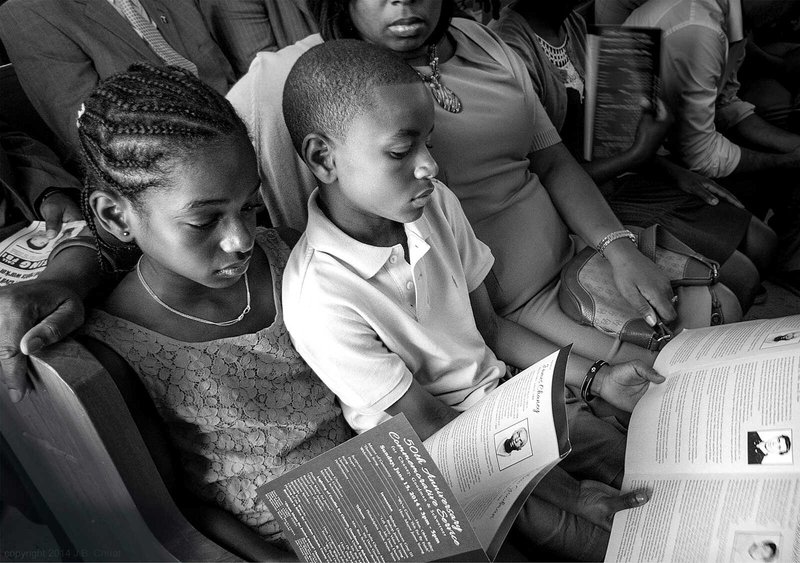

Then, on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the murders in 2004, the same impulse to host a community-wide commemoration stirred among white civic leaders, many of whom had been involved in the 1989 commemoration and who were increasingly convinced that the county’s economic wellbeing was tied to its past. Under the leadership of Leroy Clemons, the President of the local chapter of the NAACP, and Jim Prince, Dearman’s successor at The Neshoba Democrat, an interracial group of local citizens—including members of Mt. Zion—emerged as a commemoration planning task force (later identifying as the Philadelphia Coalition). They were an eclectic bunch, both ideologically and demographically, united in a common cause: to commemorate the 1964 murders. Meanwhile, another group was also planning a 40th anniversary commemoration. This group, led by Mable Steele’s son John, assembled to continue the family’s legacy of organizing annual memorials for Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman. Mississippi civil rights movement veterans joined with Steele’s group, including Diane Nash, Curtis Mohammed, George Roberts, C. T. Vivian and, most notably, Ben Chaney.

While the groups sought to reconcile their differences, distrust plagued the interactions between the Philadelphia Coalition (who were accused of capitulating to the white business community) and Steele’s group (who were portrayed as “outsiders” in local news editorials, despite Steele and Chaney’s deep roots in the county).

The two groups were divided over whether to uphold Mt. Zion’s traditional yearly observance or to broaden the audience of the commemoration by hosting it at the Neshoba County Coliseum, a location typically associated with the county’s white residents. The Philadelphia Coalition wished to invite public officials, including ones with dubious civil rights records, such as Governor Haley Barbour, Representative Chip Pickering and Charles Pickering, Sr. Ben Chaney pointed to the confederate emblem on Barbour’s state flag lapel pin, which was symbolic of the racist culture Chaney’s brother had lost his life trying to change. In contrast, members of the Philadelphia Coalition largely agreed with journalist Donna Ladd’s interpretation that Barbour’s and Pickering’s eventual appearance at the event represented a “chink, however small, in the Southern Strategy’s armour.”

On June 21, 2004, nearly a thousand onlookers gathered at the Neshoba County Coliseum to witness the 40th anniversary commemoration there, which featured notable civil rights veterans as well as Barbour and the Pickerings. A smaller ceremony at Mt. Zion followed, where longtime residents struggled to find seats, further fueling sentiments that the commemoration had been co-opted.

A year following the tumultuous 40th anniversary commemoration, the conviction of Edgar Ray Killen for his role as the mastermind behind the 1964 murders further exacerbated the divide. Critics accused the Philadelphia Coalition—which had been instrumental in having the case reopened—as being complacent with this legal victory while many of Killen’s alleged collaborators continued to live free and numerous other civil rights-era murders were yet to be addressed. Every year since, the two groups have held two separate, nearly simultaneous commemoration services.

Neshoba Countians have never been silent on the murders. On the contrary, the county’s long history of commemoration has merely been overlooked by journalists and historians who have conflated the county’s history with the history of its white citizens. The long-standing commemorative activities of Neshoba County’s Black residents, in fact, served a critical social function: they safeguarded the memory of the 1964 murders and provided the foundation for new legal redress four decades later, when there were more favorable social and political conditions. Yet these new developments have also exposed fault lines in Neshoba County that had been hiding in plain sight when white silence was the norm and Black commemorations went largely unnoticed outside of the communities where they occurred. For many who continue to commemorate the 1964 murders, the pursuit of justice remains incomplete. They continue to gather, much like their predecessors, believing that collective remembrance is a necessary precursor to social change.

Claire Whitlinger is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Furman University in Greenville, SC. She is the author of Between Remembrance and Repair: Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi (2020) and conducts research on the relationship between race, collective memory and social movements.

A new AMERICAN EXPERIENCE collection, currently featuring a selection of our award-winning films from Stanley Nelson (Firelight), documenting pivotal moments in the 20th century civil rights movement— along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with race, democracy and justice.