Biography: Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull was the political and spiritual leader of the Sioux warriors who destroyed General George Armstrong Custer's force in the famous battle of Little Big Horn. Years later he joined Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West show. A portrait of Cody and Sitting Bull together bears the title "Foes in '76 — Friends in '85." The reality was a little more complicated.

Native Warrior

Sitting Bull was born in what is now South Dakota, probably in 1831, son of a respected Sioux warrior named Returns-Again. The child wanted to follow in his father's footsteps but showed no particular talent for warfare, so he was given the name "Slow" until he could earn a better one. At age 14, during a fight with rival Crow Indians, he managed to "count coup," or strike the body of an opposing warrior with a coup stick, and was re-named "Tatanka Yotanka," or Sitting Bull, in honor of his feat. He had no use for peace with the white man — Sitting Bull once taunted rival Indians with the boast that "The whites may get me at last... but I will have good times until then." Still, the Sioux were able to live largely unmolested until 1874, when gold was discovered in the Black Hills of the Dakota territory. Although a treaty had given these lands to the Sioux, white settlers now poured in, and clashes between the two sides grew. In early 1876 all Indian people were ordered onto reservations, and soldiers were sent after those who refused. One of the soldiers was General Custer, who led his immediate command of 200 men into battle against approximately 2000 Sioux, including Sitting Bull, and had his entire command wiped out.

Show Business

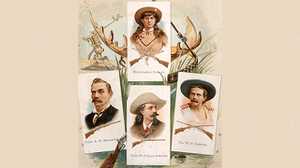

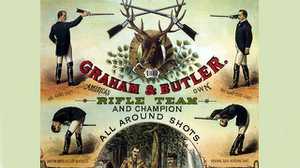

Soon after the battle, Sitting Bull fled to Canada and lived there for several years. Returning to the United States in 1881, he was held prisoner at the Standing Rock Reservation in the Dakota territory. Sitting Bull was allowed to travel with the permission of the reservation's Indian Agent, and on one of those trips in 1884 he met Annie Oakley, whose marksmanship so impressed the Sioux warrior that he offered $65 for a photograph of the two of them together. The next year Sitting Bull joined Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West show. His duties were limited — Sitting Bull rode in the show's opening procession — and he was well compensated, earning 50 dollars a week plus the money he made from selling autographs. He was treated kindly by Oakley, who said the Sioux warrior "made a great pet of me." Sitting Bull also met the "new White Father at Washington," President Grover Cleveland. But life on the road was sometimes unpleasant.

Crowds hissed, newspapers termed him "as mild mannered a man as ever cut a throat or scalped a helpless woman," and in Pittsburgh the brother of a soldier killed at Little Big Horn attacked him. He was shocked by the poverty, he witnessed in his travels, especially among children. When the season ended in October, the 54-year-old Sioux warrior decided to go home. "The wigwam is a better place for the red man," he said.

Cody and Sitting Bull

Cody, who had served as a scout during the 1876 war but never encountered Sitting Bull on the battlefield, had a complicated relationship with the Sioux warrior. On one level, they were friendly enough, and Buffalo Bill termed him "that wonderful old fighting man."

The Ghost Dance Movement

When Sitting Bull was denied permission to return to the Wild West in 1886, the show went on without him. But then in 1889, a mystic named Wovoka began having visions during a solar eclipse that the white man would vanish if Indians would perform "ghost dances." The movement spread across Indian reservations, and Sitting Bull joined in. Alarmed federal officials feared a general uprising, and one sent Cody on a mission to negotiate with his old show business comrade. But the two never met—on December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was shot by a group of Indian police who had been sent to arrest him. In the midst of the gunfire, Sitting Bull's stage horse, a gift from Cody, began performing its old routine, lifting its leg as if to shake hands. Cody would later say that if he'd only gotten to Sitting Bull in time, the whole tragedy would have been avoided. Annie Oakley was even more blunt. If Sitting Bull had been a white man, she said, "someone would have hung for his murder."

After centuries of encroachment, warfare and neglect, Native Americans remain a vital force in the life and culture of America. In this collection, explore stories celebrating and honoring the history and lives of Native Americans—throughout history and today.