Hunting the Plague

In 1900, doctors raced to save San Francisco from a disease that had killed hundreds of millions around the world

The Victim

Wong Chut King’s death nearly went as unnoticed as his life. If not for bureaucratic necessity, the 41-year-old Chinese immigrant would have escaped the ignominy of going on record as the first known victim of bubonic plague in the United States. Instead, Wong’s passing on March 6, 1900 sounded a death knell the country’s health inspectors had long feared. Suddenly, every detail of his existence became a clue that might help them ward off an illness that had killed hundreds of millions over the course of six centuries.

Wong’s was a meager existence, common to other “bachelors” in San Francisco’s Chinatown living halfway around the world from their families. Nearly 14,000 of the city’s residents lived in a 12-block parcel shaped, in equal parts, by affinity and discrimination. San Francisco’s Chinese inhabitants were barred from living in other parts of the city, confining them within conscribed borders, while white landlords charged extortionary rents and left properties in the district unmaintained.

Two decades after his immigration, Wong still subsisted in the city’s margins, traveling the short distance from his work at a lumberyard and what could only charitably be called home in a crowded lodging house. His rank, dark, below-ground room at the Globe Hotel on Dupont Street was shared with several other men; they took turns sleeping on a wooden bed on the floor in shifts. Dug into the ground was a pit that functioned as their only toilet, and rats above them came and went via an unused sewer pipe.

The start of the new lunar calendar in February 1900—inaugurating the Chinese Year of the Rat—brought only bad omens for Wong. In late February he fell gravely ill. A consultation with a traditional Chinese doctor did nothing to heal the torturous lump, a swollen lymph node, in Wong’s groin. He quickly found it excruciating to urinate or even move his leg. He stopped showing up for work at the lumberyard.

Wong lay in his crowded den with a soaring fever; he threw up his last meal; his bodily functions failed. Only a few days after first discovering the dark nodule at his pelvis, Wong fell into a coma from which he never returned. His roommates carried his febrile body to its final destination, an undertaker’s shop with a room that locals called a “hall of tranquility,” where the terminally ill with no local family often spent their last moments. Several days later Wong succumbed to the disease that had ravaged his body.

No one would have taken note of his death, but for an administrative requirement compelling the undertaker to call local police to issue a burial certificate. After inspecting Wong’s corpse, alarmed city health officers took samples from the inflamed tissue around his lymph glands. They understood that the evidence before them could portend a public health crisis at unimaginable scale. Even more troubling, although Wong’s was the first observed case of the plague in San Francisco, there was no way to know whether he was truly Patient Zero.

Only hours after his death, the city’s Board of Health called a late-night emergency meeting where its members decided to enact a preemptive quarantine of Chinatown. With the discipline of bacteriology still in its infancy, racist pseudoscience at the time attributed all manner of disease to the Chinese. The bubonic plague in particular, San Francisco’s Citizens’ Health Committee noted several years later, was considered “an Oriental disease, peculiar to rice-eaters.” “The Chinese cancer must be cut out of the heart of our city, root and branch, if we have any regard for its future sanitary welfare,” the Board of Health offered in an official condemnation of Chinatown already in 1880, adding, “it is a shame that the very centre [of the city] be surrendered and abandoned to this health-defying and law-defying population.”

Now, under cover of darkness, dozens of police officers rushed to cordon off the district, as though their thin rope might contain not just people but a pandemic.

The Plague

When the bubonic plague claimed Wong Chut King, no one in the United States understood how the disease was transmitted. What was known was how rapidly it could lay waste to a city. In The Decameron, the Italian writer and poet Giovanni Boccaccio described how the epidemic struck Florence in 1348. “So many corpses would arrive in front of a church every day and at every hour,” wrote Boccaccio, “that the amount of holy ground for burials was certainly insufficient for the ancient custom of giving each body its individual place; when all the graves were full, huge trenches were dug in all of the cemeteries of the churches and into them the new arrivals were dumped by the hundreds; and they were packed in there with dirt, one on top of another, like a ship’s cargo, until the trench was filled.” The plague’s first wave killed an estimated quarter or more of the population of all Europe between 1347 and 1350.

During London’s second plague outbreak in the 17th century, nearly a quarter of its population died in a year and a half. “The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them,” wrote Daniel Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year, published a half century after the epidemic. So-called “dead-carts” made rounds throughout the city to haul away bodies, attended by cries of “Bring out your dead.”

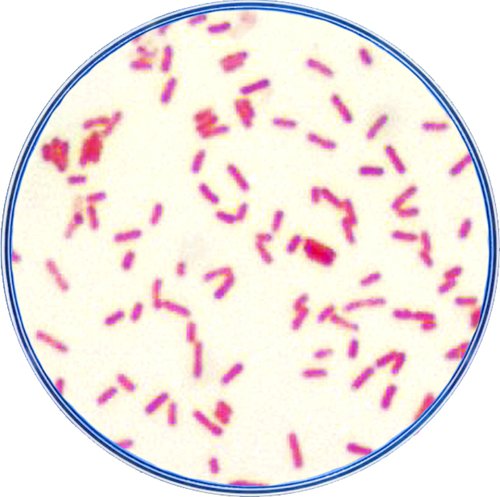

Several hundred years would elapse before the cause of death swam into focus on a slide. In 1894, French researcher Alexandre Yersin identified the source of plague: a microscopically small, rod-shaped bacterium given the name, in acknowledgment of his discovery, of Yersinia pestis.

The bacteria’s effects and its rapid progression were by then well-documented. Once Y. pestis gained access to the human body—still how, no one yet knew—its bacterial load doubled every two hours. A victim’s symptoms started with a raging fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. Within the week their lymph nodes, sentinels of the body’s immune system, were overrun with bacilli, and swelling at the groin, neck and armpits formed painful buboes that gave the bubonic plague its name. As the disease coursed through the body, it led to septic shock and then organ failure. The victim’s blood vessels burst, making hands and feet appear as though they’d been stained in blue-black ink, a dire and telltale sign of the “Black Death.”

Yersin reached his 1894 breakthrough in Hong Kong as China was suffering an outbreak of the bubonic plague that left 10 million dead in just five years. From that one port city, the disease traveled to others—Kobe, Japan and Honolulu, Hawaii—all the time accelerated by steamship. With Wong’s death, it was clear that the Plague had crossed what remained of the Pacific, reaching San Francisco and the entire North American continent.

However, in addition to harboring the country’s first known victim of the plague, the city was also home to the first American to study the bacterium. Now, it remained to be seen whether that same expert would be able to warn San Franciscans of its danger.

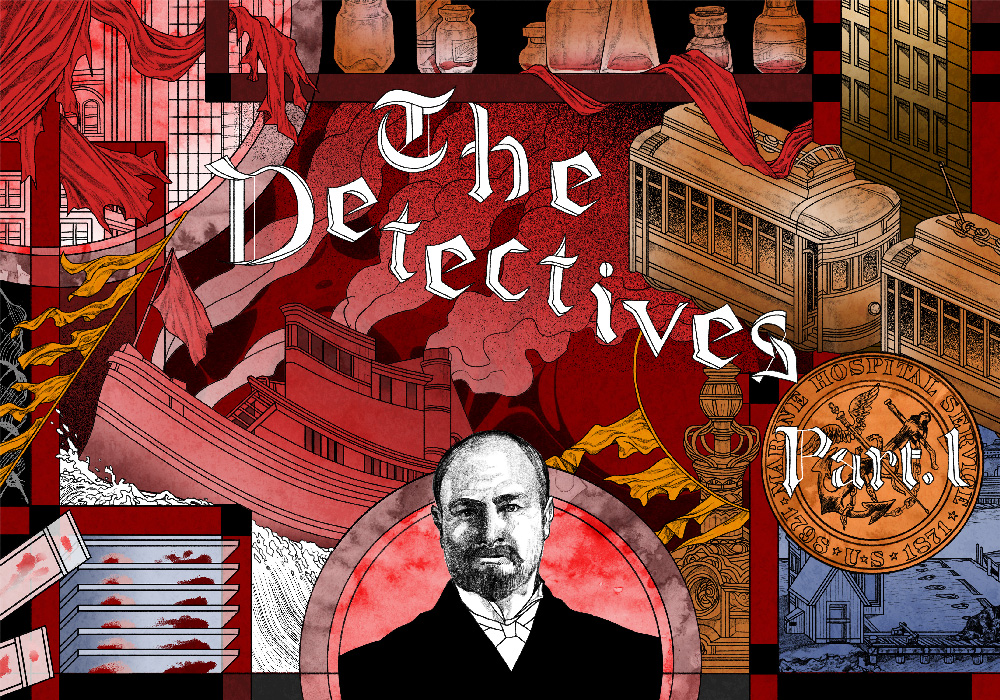

The Detectives—Part 1

It was a blustery 40-minute ferry ride from the city across the San Francisco Bay and around to the north side of Angel Island—home to both the country’s largest quarantine station and the man with the experience to definitively pronounce the plague’s existence on U.S. shores.

At the turn of the 20th century, bacteriology was still a fledgling discipline, and 39-year-old Dr. Joseph Kinyoun was one of its most highly trained practitioners. By 27, Kinyoun had established the first federal bacteriology laboratory on Staten Island, where he also became the first person in the Western Hemisphere to identify cholera. He then studied in Paris with Louis Pasteur and in Berlin with Robert Koch, two founders of the nascent science of germ hunting. By the time the Surgeon General, Walter Wyman, dispatched Kinyoun to San Francisco in June 1899, the latter had also invented some of the world’s first disinfecting devices and developed and tested the first smallpox serum for human treatment.

After these groundbreaking feats, Kinyoun resented his remote posting as west coast sentinel for the Marine Hospital Service (MHS). Directing the immigration hub had torn him away from his beloved Washington, D.C. lab. Now on any given day, he spent considerably more time inspecting travelers’ bodies and baggage for infection than he did poring over slides, his true passion. Kinyoun was by training and temperament a researcher, a background that left him ill prepared for directorship of the MHS quarantine station.

The crisis at hand quickly pushed away thoughts of professional discontent, however. Kinyoun took hold of the glass vials containing Wong’s tissue and lymphatic fluid, the key to confirming a plague diagnosis. What he spied under the microscope looked like Yersinia pestis, but to obtain full proof he would need to grow more of the bacteria in a culture, while also inoculating lab animals to see if they too developed the same symptoms Wong had exhibited. Three days later, all of the lab animals lay dead in their cages—but by then San Francisco had already turned against him.

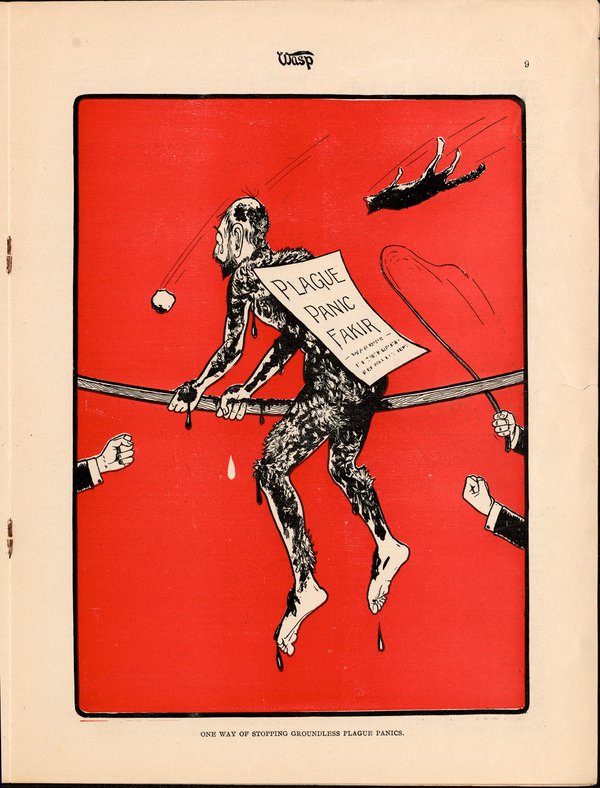

Local newspapers and business interests feared the economic disruption a plague diagnosis would induce more than the disease itself. The media even accused health officials of concocting the scare as a ruse to get more public funding. “Plague Fake is Part of a Plot to Plunder” blared a San Francisco Call headline, just 48 hours after Wong’s body was discovered. The city’s Mayor and Board of Health caved to public and private pressure, and the quarantine of Chinatown was lifted before Kinyoun was even able to announce the results of his investigation. Over the course of the next week, Kinyoun confirmed the deaths of eight more Chinatown residents by bubonic plague; others likely fell victim to it as well, but were concealed from public view or improperly diagnosed. Their deaths did nothing to turn public opinion.

Over the next 14 months, Kinyoun engaged in a pitched battle with the media and state officials at every level over his attempts to defend the city from the disease he feared would beget its ruin. Still, there was a key question he was unable to answer, and one that his critics regularly lodged: Why weren’t more people dying? Where the current wave of plague had reached Bombay, Calcutta, Hong Kong and Sydney, those cities had observed far more cases. Something was keeping the death toll from exploding into an epidemic.

Nevertheless, by April 1901, Kinyoun’s chance to solve the mystery reached an end. Surgeon General Wyman gave the doctor marching orders to depart San Francisco to another MHS outpost in Detroit. Kinyoun simply had too many enemies in California. On the one hand, his mulish, pedantic approach had put off potential allies, and on the other, powerful commercial and political interests wouldn’t admit the danger facing their state and country, relatively low casualties notwithstanding. Embittered, Kinyoun left behind a city that had yet to face the plague—or figure out the path by which it was winding its way from one victim to the next.

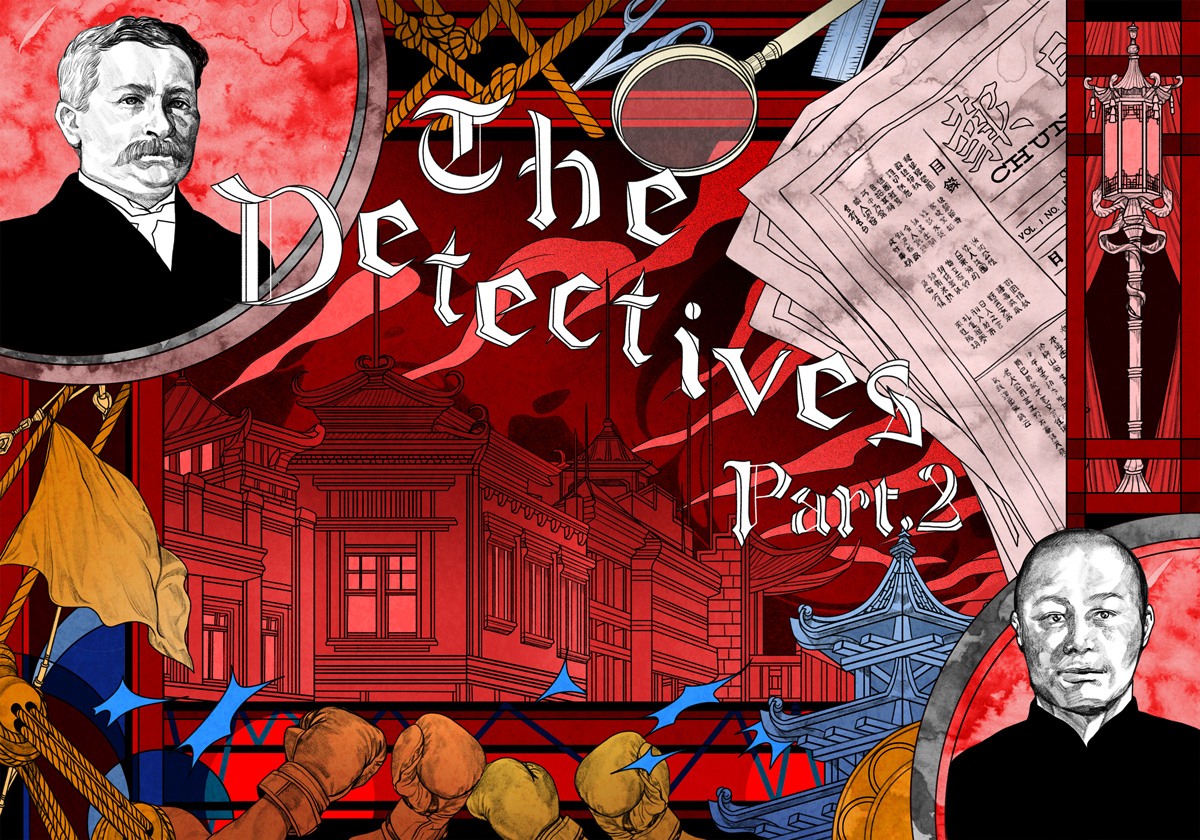

The Detectives—Part 2

Dr. Rupert Blue wasn’t the first, or even second candidate to take over the hunt. The first person who replaced Kinyoun at the head of the Angel Island quarantine station requested a transfer after only two months, citing the hopelessness of trying to convince San Francisco’s leaders to take the plague seriously. Other candidates whom Surgeon General Wyman approached promised to leave the MHS before they would take the position.

But what Blue lacked in medical training he made up for with a different, and arguably more important skillset: the art of bobbing and weaving. An avid boxing fan and amateur pugilist, the 33-year-old Blue took a different tack than his predecessor. Rather than forcing direct confrontation with California’s power brokers or Chinatown’s inhabitants, who with good cause distrusted public health officers, Blue ingratiated himself with both. He might not have had Kinyoun’s bona fides—Blue’s academic record at the University of Virginia and University of Maryland School of Medicine was entirely undistinguished, marked more by grit than genius—but he instead had something San Francisco needed much more urgently. Blue possessed the social intelligence to see through scientific data to the people they signified. Helping them, he instinctively knew, would require winning them over first.

He first dared to do what no MHS officer had yet ventured: For 75 dollars a month, Blue set up an office on Merchant Street in the heart of Chinatown. A block away was Portsmouth Square, a plaza at the center of the district; the headquarters of the Chinese Six Companies, a consortium of the neighborhood’s most powerful businesses, was only a few streets west.

By embedding himself where others’ prejudice kept them at a distance, Blue made a statement to his new neighbors about collaboration—something he further emphasized by walking Chinatown’s streets unprotected, where Kinyoun had always been accompanied by a security detail. Blue also came up with an innovative approach to gain access to victims whose bodies might otherwise be hidden from official eyes. For an additional 35 dollars monthly MHS outlay, he arranged for a driver, horse and cart to pick up bodies immediately after word of a death in the district reached his new headquarters.

Blue also realized he needed help navigating a culture and a language he didn’t understand. Wong Chung, a former secretary for the Chinese Six Companies, had previously served as an interpreter to a commission of white doctors, assisting them in finding the first living plague patients. Given the discriminatory thinking behind MHS interactions with the district, however, no one had thought to retain Wong beyond that one investigation. Blue now offered Wong 20 dollars per month—almost $4000 today—to join his staff full-time, the same salary paid to white interpreters.

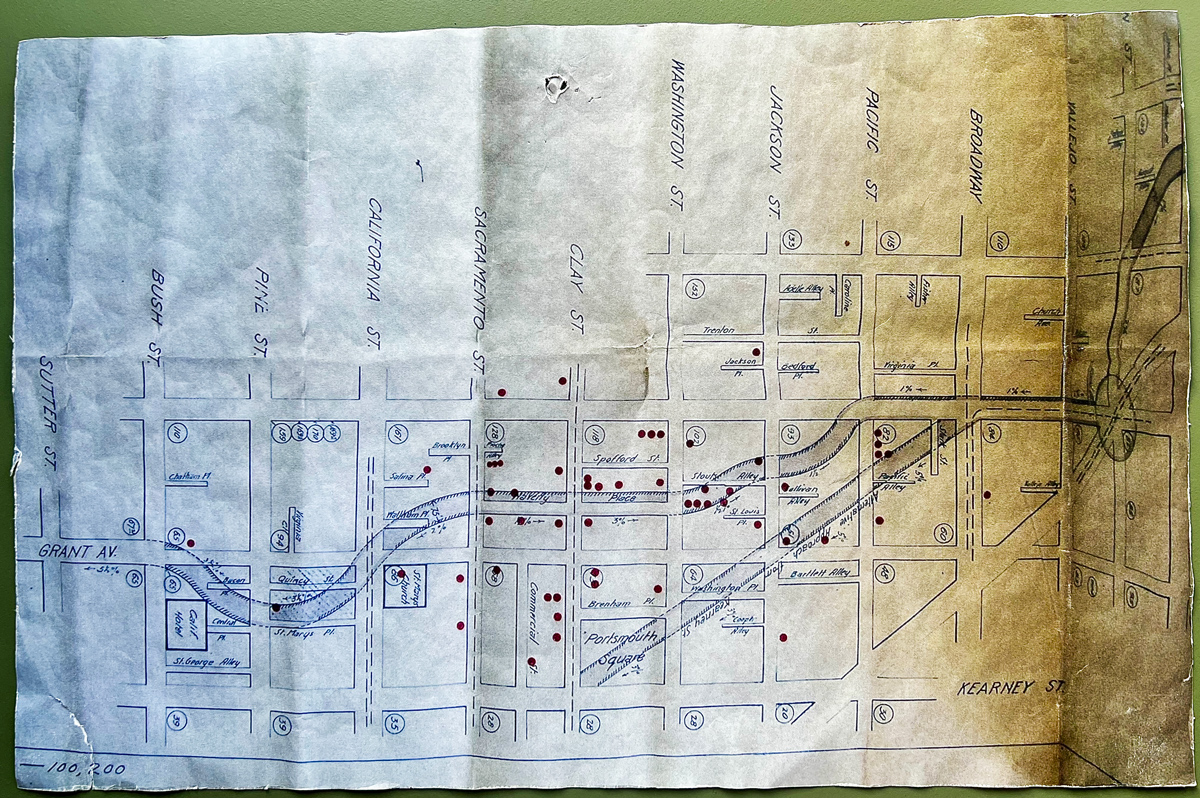

Every good detective needs a good deputy. The fictional Sherlock Holmes had Watson; Rupert Blue had Wong Chung. And elevating Wong from the status of translator to cultural liaison—and fellow plague-hunter—paid nearly immediate dividends. In September of 1901, Wong delivered Blue a big break. He tipped the doctor off to a near-death case of the plague, a 28-year-old man whose friends, fearing retribution from the gods and city officials, tried to transfer him out of the city. Not only was Blue able to question a still-living plague sufferer, his handling of the situation won support in the community. Chinatown’s inhabitants saw that he was investigating in good faith, not simply as a pretext to more enforced segregation. “We are still working quietly, avoiding friction with… the Chinese,” Blue wrote Wyman. More hidden cases began to come to light, yielding 10 additional plague diagnoses that allowed Blue and his team to practice more informed pattern recognition. A man obsessed, he stared at a map of Chinatown pinned behind his desk, with each known infection marked with a dark red dot.

It was a death later that month that provided Blue with a missing piece of the puzzle he had been trying tirelessly to solve. On September 27, a 53-year-old Bavarian immigrant, Marguerete Saggau, died after a four-day bout with what proved to be the bubonic plague. Saggau and her husband and son lived at the Hotel Europa on Broadway where she worked as a laundress. Blue repeatedly paced the building in search of a vector that would connect the plague’s most recent known casualty with the others before it. A theory finally emerged. “[T]he Hotel Europa,” Blue wrote to his boss, “is only one block north of Chinatown, a distance easily covered by rats in their migration.”

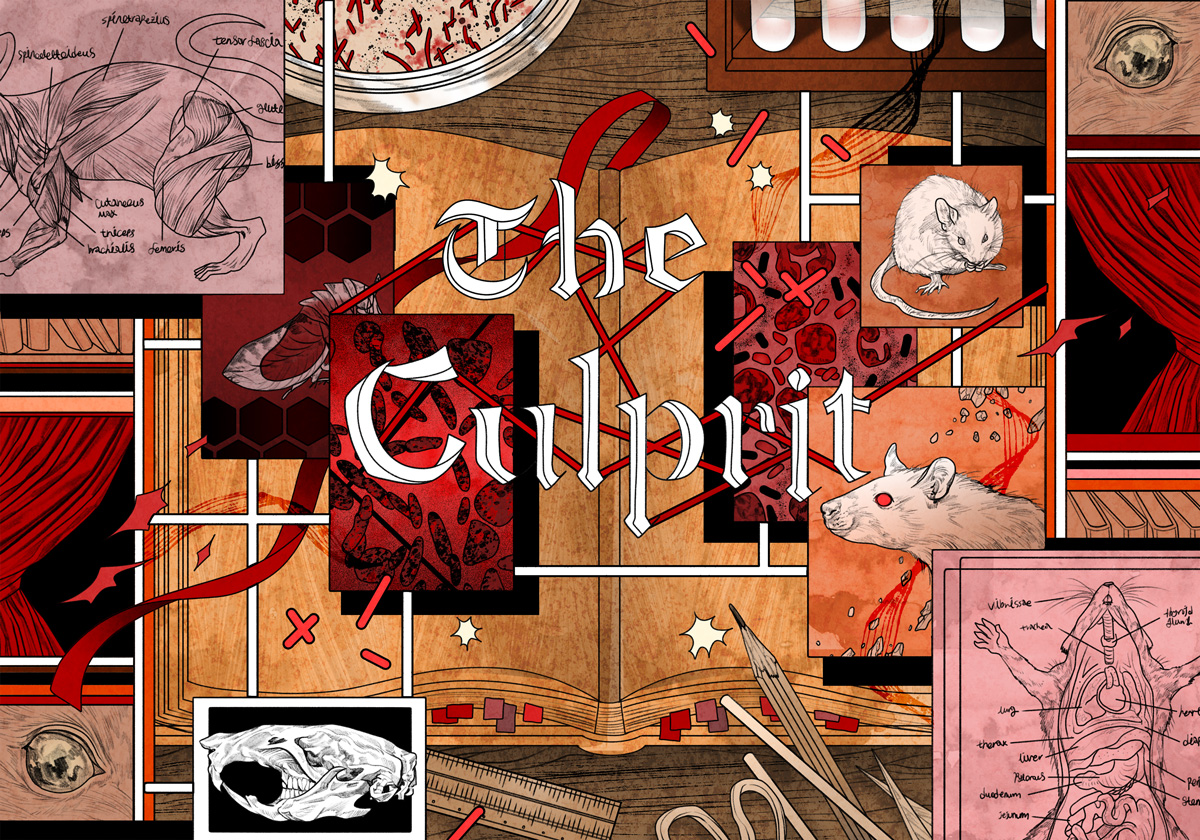

The Culprit

The connection between rats and pestilence was long suspected before Kinyoun, Blue and Wong tried to defend North American shores from the plague’s third global wave. Earlier societies understood the importance of controlling one to contain the other. Defoe remarked upon it in his 1665 chronicle: “All possible endeavours were used also to destroy the mice and rats, especially the latter, by laying other poisons for them, and a prodigious multitude of them were also destroyed.” Most recently, Yersin had noticed mounds of dead rats when investigating Hong Kong’s 1894 outbreak; autopsies uncovered the same bacteria he also identified in human victims. Turn-of-the-century San Francisco, and particularly densely crowded Chinatown with its makeshift accommodations poorly maintained by slumlords, was a perfect breeding ground.

Blue’s plan for cleaning the district, like his other approaches, was unorthodox: He wanted to focus specifically on eradicating the city’s rodents as a means of combating plague. Still, it wasn’t the rising death toll that finally forced California’s public officials to admit that the city needed to clean itself up. While they cared little about a health crisis, the crisis of reputation facing the state—and by extension threatening its economy—gave Blue both the leverage and funding he needed to launch a sanitation campaign. The MHS began aggressively exterminating rats and eliminating their sources of food and shelter. Hundreds of wooden structures in Chinatown were demolished and replaced by more tightly sealed brick-and-mortar buildings.

The culprit had been hiding in plain sight—or so it seemed. But even if rats were the plague’s primary carriers, just how were they infecting humans?

The missing link was discovered just a few years after Yersinia pestis was first identified. Another French researcher, Paul-Louis Simond, noticed something critical when studying patients still in the early stages of infection. Upon inspecting their skin, Simond observed that small incisions, also laden with plague bacteria, always preceded the buboes that swelled beneath the skin more prominently later—and that the smaller cuts were just the size of an insect bite. Simond combed the bodies of dead rats collected at victims’ homes. The rats proved to be riddled with fleas which, when examined under the magnified lens of a microscope, were themselves laden with plague bacteria. Simond theorized that fleas feasting on a diseased rat would seek another host once that first rat died, and so transfer the disease to a new host, whether rodent or human.

Blue knew of Simond’s work, but it wasn’t until 1903, the same year he spearheaded San Francisco’s mass clean-up, that French doctors confirmed that transmission of plague happened via host-hopping fleas. And Blue had specific evidence in the city by the bay: a 35-year-old Italian laborer took ill and died after bringing back wood scavenged from Chinatown’s reconstruction to his home in the Latin Quarter. The planks, Blue deduced, were teeming with fleas. His clean-up effort expanded to include more territory within the city.

Though they didn’t know it at the time, Blue’s team also eventually solved one of the ordeal’s most vexing local mysteries—the question of why San Francisco’s plague hadn’t evolved to become a full-blown epidemic. In 1908, their microscopic examination of thousands of fleas yielded the unexpected insight that the city’s most standard genus was Ceratophyllus fasciatus—a Northern European species—and not Pulex cheposis, the type of flea most common to Asian cities where the plague had run rampant. Blue’s researchers also discovered key differences in the two fleas’ morphology. What they didn’t know was that this simple structural difference precisely explained why the bubonic plague killed fewer people in North America. The tiny flea terrorizing populations across the Pacific simply disgorged more plague bacteria into its victims because of the size of its guts.

Where racist theories had pointed to the Chinese as the source of illness, Blue followed the evidence and focused on pests rather than people. City and state leadership—and even Kinyoun before him—had let prejudice bias their investigations.

In 1909, after San Francisco’s eradication of the disease, the city’s Citizens’ Health Committee drew up a report summarizing the effort to defeat what for years had been Blue’s personal obsession. Fittingly, he was given the task of writing the report’s final entry. “One of the great factors in the spread of plague infection is the faulty construction of the habitations of man,” he wrote, concluding with a statement of ringing finality: “Hereafter quarantine against plague should be directed against rats rather than against persons.”